Preparing for the Reader

The Reader Movie Trailer. While a few location scenes took place in New York, The Reader was primarily filmed in several German cities including Berlin, Gorlitz and Cologne, with some outdoor sequences shot in the countryside on the border between Germany and the Czech Republic. According to director Daldry, “the only way to make the film was to do it in Germany, with a German crew.”

Making up the rest of The Reader’s creative team was an array of acclaimed Academy Award-winning craftspeople including director of photography Chris Menges (The Mission and The Killing Fields), editor Claire Simpson (Platoon), costume designer Ann Roth (The English Patient) and production designer Brigitte Broch (Moulin Rouge).

For production designer Broch, working on the film awoke some long-dormant memories. A native German who moved to Mexico four decades ago, she considers herself part of the “second generation” who grew angry with their parents and their silence about what occurred during the war. Making The Reader forced her to face her own society in a way she’d never done before. “It’s actually the first time that I dared to personally confront myself with it and say, okay, enough with fear, enough with guilt, I have to face it,” she says. “It was hard emotionally, like diving into the depth and somehow coming out on the other side.”

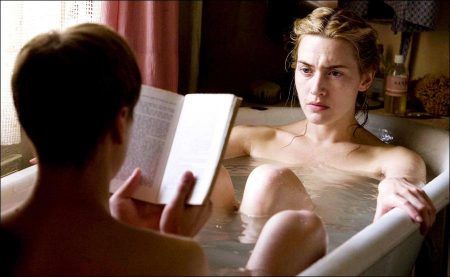

The actors, too, found certain elements of the story extremely difficult to handle. “Usually I love doing preparation,” says Winslet. “It’s so important to have done your homework and then let it all go. But for Hanna I had to read so much literature and watch so many documentaries about the concentration camps that, at a certain point, I couldn’t take it any more. There are so many images I know will never leave me, no matter how hard I try.”

The process of aging her character over thirty years introduced Winslet to yet another aspect of filmmaking, made only a bit easier with the help of hair and makeup designer Ivana Primorac, a BAFTA nominee for her work on Sweeney Todd and Atonement. “To portray the older incarnation of Hanna, make-up and the prosthetic body work took four hours,” recalls Winslet, who wriggled into a latex body suit to portray her aging, flabby frame instead of using easier, but less effective, padding under her costumes. “My whole body language changed,” she says, noting that others seemed shocked by her appearance while she took it in stride. “I didn’t mind looking in the mirror and seeing myself as an old hag,” she says, with a laugh. “It gave extra dimension to the character.”

Fiennes explained his process of preparing for the role with director Daldry. “He was always asking questions, which is great,” recalls the actor. “What does Michael really think about Hanna? How do you condemn someone you’ve been intimate with? Is that intimacy still something you hold close to you? He kept those questions circulating which was crucial, because there isn’t really one answer. But even with all these questions, Stephen was firmly nurturing. He takes the time to let you discover a scene, and he has the confidence to allow for changes over the course of a day or even during the shooting of a scene. It’s a great way to work because it gives the actor freedom.”

Planning and plotting out his character’s back-story was a new experience for young actor David Kross. “It’s the first time I’ve learned to do background research for a role,” he says. “Stephen took me to the Jewish Museum in Berlin, and bought five bags of books for me to study. It was then I realized how little I really knew about the Third Reich.”

Daldry and his crew were helped enormously in their quest for realism by the Fritz Bauer Institute in Frankfurt, a major repository for material relating to Nazi war crimes. Researchers at the Institute, led by Werner Renz, provided the movie’s art department with photographs, transcripts and other background that proved invaluable for authenticating details of the war crime tribunal featured in the film.

Most of The Reader’s courtroom scenes were based on the Frankfurt Auschwitz trails held between 1963 until 1965, in which 22 mid- to low-level workers from the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp were prosecuted. In stark contract to the earlier, more infamous, Nuremberg Trials of top SS officers, Gestapo leaders and others, the Frankfurt hearings revealed the wider array of Holocaust enablers and enforcers.

In fact, many real life attorneys and retired magistrates from that era appeared in the film portraying lawyers and judges, including Thomas Borchardt, Thomas Paritschke, Burglinde Kinz, Stefan Weichbrodt and Kark Heinz Oplustiel. Other legal scholars, such as Auschwitz prosecutor Gerhard Wiese and Judge Gregor Herb, served as consultants.

Furthering their desire for authenticity, Kross and a small crew spent a full day and night filming a sequence at the Stutthof concentration camp in Poland, where Michael roams the grounds and imagines the horrors of decades past. “It was one of the most extraordinary days of my life,” says Daldry of the shoot, which also provided its share of logistical difficulties when he was forced to film around Jewish groups from Israel visiting the area that were taken aback by the German-speaking crew.

A Nation – and a Generation – Scarred by Guilt

Knowledge of the Holocaust is assumed to have been widespread among German population during WWII. The SS had approximately 900,000 members in 1943. The German national railways employed more than a million citizens, and many would have processed the lines of cattle-cars packed with Jews being transported across the land. Other German civil service organizations directly participated in maintaining the camps, and thousands more mid- and low-level bureaucrats must have been aware of what was transpiring.

As a law student says in The Reader, “There were thousands of camps… everyone knew.”

When the war ended in 1945, an Allied consensus concluded that all Germans shared blame not only for the war itself but also for Nazi atrocities. Statements made by the British and US governments, both before and immediately after Germany’s surrender, mandated the German nation as a whole was to be held responsible for the actions of the Nazi regime, often using terms including “collective guilt,” and “collective responsibility.”

Even President Harry S. Truman acknowledged how difficult it was to determine those in command from those less culpable, and from those who merely turned a blind eye. In a letter to one US Senator, he explained that all Germans might not be guilty for the war, but it would be difficult to single out for relief efforts those who had nothing to do with the Nazi regime’s crimes. “I cannot feel any great sympathy for those who caused the death of so many human beings by starvation, disease and outright murder, in addition to all the regular destruction and death of war,” he wrote.

Almost immediately after the war’s conclusion, a rapid process of “denazification” began, supervised by special German ministers with support of U.S. occupation forces. At the same time the Allies, through the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force, began a massive propaganda campaign to instill a sense of collective responsibility among Germans.

Newspaper editorials and radio broadcasts were developed to make sure all Germans accepted blame for Nazi crimes. The campaign used posters with images of concentration camp victims and accompanying text declaring “You Are Guilty of This!” or “These Atrocities: Your Guilt!” From 1945 to 1952, a series of films about the concentration camps were also produced and screened for the German public including “Die Todesmuhlen” and “Welt im Film No. 5,” with the goal being to lead the “outlaw nation” back into civilized society and democracy.

The German Government’s Post-War Stance

Officially, the Allies praised Germany’s response to its war crimes. The Government of the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany until 1990) offered official apologies for Germany’s role in the Holocaust. German leaders often expressed repentance, most notably in 1970 when former Chancellor Willy Brandt fell on his knees in front of a Holocaust memorial in the Warsaw Ghetto, known as the “Warschauer Kniefall.”

Germany has paid some reparations, including nearly $70 billion to the state of Israel and an additional $15 billion to Holocaust survivors who will continue to be compensated until 2015. The German government reached a settlement with companies that had used slave labor during the war, with the firms agreeing to pay $1.7 billion to victims. Germany also established a National Holocaust Memorial Museum in Berlin for looted property. Legislation outlaws the publication of infamous Nazi works like Mein Kampf and makes Holocaust denial a criminal offence, while symbols including the swastika and so-called “Hitler salute,” are illegal. Furthermore, the government even has Israel arrange the curriculum for Holocaust education in all German schools.

Germany’s treatment of war criminals and war crimes has also met with wide approval. The country helped track down war criminals for the Nuremberg Trials and opened many archives to researchers and investigators. In addition, Germany verified over 60,000 names of war criminals for the US Department of Justice to prevent them from entering the United States and provided similar information to Canada and the United Kingdom. (Of course, not all war criminals were brought to justice and many peacefully retired in other countries.)

Despite these efforts, however, Germany has also been criticized for not doing enough to compensate for its crimes. The German government never apologized for the invasions or took responsibility for the overall war. The emphasis for blame is often placed on individuals like Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party instead of the government itself, so no restitution has been made to any other national government by Germany. Even after German reunification in 1990, Germany rejected claims for reparations made by Britain and France, insisting the matter had been resolved. Furthermore, Germany has been criticized for waiting too long to seek out and return looted property, some of which is still missing and possibly hidden within the borders of the country. Germany has also had difficulty retrieving some stolen property because of a need to compensate the owners.

Finally, Germany refused to allow access for decades to the International Tracing Service’s Holocaust-related archives in the town of Bad Arolsen, citing privacy concerns and other issues. In May 2006, a 20-year effort by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum led to an announcement that millions of documents would finally be made available to historians and survivors.

But What of the Next Generation?

The Reader author Bernhard Schlink and his German contemporaries were in a unique position—they were wholly blameless for their parents’ crimes, yet they were born and raised under in the shadow of these great atrocities. How his generation, and indeed all generations after the Third Reich, comes to terms with the crimes of the Nazis, is what Schlink refers to as “the past which brands us and with which we must live.” And, as a law professor says in the film, “What we feel isn’t important—what’s only important is what we do.”

Screenwriter David Hare explains, “The Reader is best known German novel about the post-war years and the impact of the Nazis on the Germans themselves. Very little written about what happened to the succeeding generation dealt with the guilt of being born at a time when, through no fault of their own, they inherited this massive crime.”

Schlink adds, “We all condemned our parents to shame, even if the only charge we could bring was that after 1945 they had tolerated the perpetrators in their midst… The Nazi past was an issue even for children who couldn’t accuse their parents of anything, or who didn’t want to.”

Schlink chose to exorcise his demons on the page. He presents his readers with Hanna, and he underlines her crime so it can be both clearly defined and considerably damned, walking a fine tightrope between the two positions. He admits via Michael, “I wanted simultaneously to understand Hanna’s crime and to condemn it. But it was too terrible for that. When I tried to understand it, I had the feeling I was failing to condemn it as it must be condemned. When I condemned it as it must be condemned, there was no room for understanding … I wanted to pose myself both tasks — understanding and condemnation. But it was almost impossible to do both.”

The book itself was not without controversy itself. Says Hare, “You can’t write about post-war German guilt without it being hugely contentious.” First of all, Schlink put a perpetrator rather than a victim at the center of his story, which represented a huge departure in Holocaust literature. And his approach toward Hanna’s culpability became a frequent source of conflict, with the author frequently accused of revising or falsifying history to make his characters more acceptable. In the “Süddeutsche Zeitung,” Jeremy Adler accused Schlink of “cultural pornography” and claimed the novel simplifies history by allowing its readers to identify with the perpetrators.

Schlink has said he finds most criticism over Michael’s inability to fully condemn Hanna comes from those closer to his own age. Older generations that lived through those times are less critical, he says, regardless of how they actually experienced the war.

Hanna and Michael’s relationship enacts, in microcosm, the delicate balance between older and younger Germans in the postwar years: “… the pain I went through because of my love for Hanna was, in a way, the fate of my generation, a German fate,” Michael concludes in the novel.

Throughout the film, there are scenes of construction taking place in the background—during Hanna and Michael’s torrid affair, and even later when Ralph is a successful lawyer and Hanna has, physically at least, been long gone from his daily life. The country was struggling to rebuild, not just its homes and offices and structures, but also its national character.

Michael represents the New Germany, and Hanna the Old. That is why the difference between their ages is as large as it is—and why they need to be a complete generation apart. Hanna is apathetic about what has happened; Michael is angry and demands answers. “It doesn’t matter what I feel, it doesn’t matter what I think,” says Hanna in one of the film’s climactic scenes, still refusing to feel remorse for her past. “The dead are still dead.”

In the novel, Michael asks, “What should our second generation have done, what should it do with the knowledge of the horrors of the extermination of the Jews? We should not believe we can comprehend the incomprehensible, we may not compare the incomparable, we may not inquire because to make the horrors an object of inquiry is to make the horrors an object of discussion, even if the horrors themselves are not questioned, instead of accepting them as something in the face of which we can only fall silent in revulsion, shame and guilt. Should we only fall silent in revulsion, shame and guilt? To what purpose?”

The Reader (2008)

Directed by: Stephen Daldry

Starring: Kate Winslet, Ralph Fiennes, Alexandra Maria Lara, Bruno Ganz, Linda Bassett, Karoline Herfurth, Susanne Lothar, David Kross, Florian Bartholomäi, Friederike Becht

Screenplay by: David Hare

Production Design by: Brigitte Broch

Cinematography by: Roger Deakins, Chris Menges

Film Editing by: Claire Simpson

Costume Design by: Donna Maloney, Ann Roth

Set Decoration by: Karin Betzler, Eva Stiebler

Art Direction by: Anja Fromm, Christian M. Goldbeck, Stefan Hauck, Erwin Prib, Yeşim Zolan

Music by: Nico Muhly

MPAA Rating: R for some scenes of sexuality and nudity.

Distributed by: The Weinstein Company

Release Date: December 10, 2008

Views: 335