The Reaping Movie Trailer. But where Katherine approaches these mysteries believing she’ll find a scientific explanation, Ben hopes to confirm his own religious faith. “It’s an interesting dilemma between them because Katherine is a complete atheist now and has no interest in finding a real miracle,” explains Elba. “In fact, when she arrives at a place where there’s a socalled miracle, she’s just short of laughing out loud when she sees what’s really going on. In contrast, Ben is doing this for his own religious beliefs–to prove that God exists, scientifically.”

“Our characters in the movie are best friends,” says Swank. “They know each other really well, inside and out. They work together every single day. They could finish each other’s sentences. And it’s funny: when I met Idris I felt an instant connection. We had a great time together.”

“When you work with Hilary you have to bring your ‘A’ game,” says Elba. “You understand why she has had such success because she’s absolutely focused all the time. She’ll sit and share a joke with you, but as soon as it’s time to work she’s like a completely different person. But she’s also a really kind, loving, warm person, as well.”

Hopkins had worked with Elba on a pilot and brought him along to an event to introduce him to Silver. “He’s just tremendously handsome and charismatic, and he and Hilary had a great rapport, which carried over to the screen,” the director asserts. “Idris is this huge, seemingly intimidating guy, but you just want to be his pal. And he can play anything. He’s just an awesome actor.”

Elba was likewise inspired by Hopkins’s style of directing: “I’m a nerd when it comes to detail, so I really admire Stephen’s work. Absolutely everything in each frame matters to him. Every frame is like a picture’s he’s painting.”

Stephen Rea, who previously starred in producer Silver’s “V For Vendetta,” joined the cast as Father Costigan, a priest who was also a missionary in the Sudan when Katherine’s family was killed. Now living in the States, Costigan receives what he interprets to be a warning about his former colleague. “She is not anxious to hear from Father Costigan because she associates him with the tragedy that befell her family,” says Rea. “But he persists because he believes she’s in great danger now. Of course, she no longer believes in spiritual signs, so he finds it quite difficult to get through to her.”

“I’m a massive fan of Hilary Swank and have been since ‘Boys Don’t Cry,’ so it’s been a great pleasure to work with her,” Morrissey says. “She brings real complexity and vulnerability to this role, and all of our scenes together were extremely involving. Doug becomes Katherine’s touchstone in this town. Like her, he has lost loved ones, and as he leads her into this odyssey, he is gradually earning her trust.”

olving. Doug becomes Katherine’s touchstone in this town. Like her, he has lost loved ones, and as he leads her into this odyssey, he is gradually earning her trust.”

“On the surface, Doug a very nice man, and seems to be a very rational man as well,” Hopkins notes. “But there is something dark lurking beneath that surface, which David manages to balance in a very compelling way.”

Morrissey relates that his character sees himself as the voice of reason in a panicked community, “The local people have witnessed these mysterious events, starting with a murder and then the river turning to blood, and immediately believe that they are seeing the wrath of God. Doug Blackwell takes it upon himself to calm the town council long enough to prove that whatever happened to the river is a natural phenomenon and not a plague sent to curse them. He’s really pinning all his hopes on Katherine to help him.”

Though she’s busy with a full academic schedule, Katherine reconsiders when she hears that a young girl is being blamed for the unusual occurrences in Haven. “Katherine has lost a daughter, so she knows what it is to lose a child that you have brought into the world—something I can’t imagine,” says Swank. “When Doug says to her that the town thinks it has something to with a little girl and they want to kill her because of it, that gets her attention. Though she may not recognize it consciously, the assignment represents a chance to save one child…and maybe redeem her past.”

The final piece of the puzzle is that child, Loren McConnell, played by young actress AnnaSophia Robb, who has already played a diverse range of roles in such films as “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory” and “Bridge to Terabithia.” “She’s just such a talent,” Swank says. “Although her character says very little in the film, acting is not always about dialogue. She says so much with her face and with her expressions, through her eyes. AnnaSophia was such a joy to work with.”

“Loren is very quiet, shy and scared,” says Robb, who turned 12 after production wrapped. “She has a reason to be scared because the townspeople have tried to kill her. She lives way back in the swamps and has no real friends, so she has been hiding in the woods since all of this started. Loren’s not very educated. She just reacts without thinking, instinctively, like an animal.”

Tucked away from the pace and progress of the big city, Haven is a community where relations are tight and faith is strong. “I have spent some time in the South and there are some places that are really hidden away,” says Hopkins, “like a secret world inside the Bible Belt, where people with their own beliefs can exist almost completely independent of the outside world.”

In Haven, Katherine and Ben are confronted with a river turned to blood, an unknown disease befalling area cattle, and a mounting number of unexplainable occurrences. “The first plague is a river turned to blood,” comments co-producer Richard Mirisch, “and, at first, Katherine thinks it’s a chemical response. Of course, as the movie progresses and the situation becomes a bit more complex, she is forced to question her own beliefs about what may be happening in these very extreme situations.”

As they take samples and send them back for analysis, one thing becomes clear—none of Katherine’s theories are panning out. To save Loren and stop the acceleration of the attacks, she will need to seek other resources outside of the scientific realm. “This movie, to me, is about a woman who loses her faith over certain circumstances in her life,” says Swank. “So, this journey for her is a kind of awakening. Things happen for a reason, and her past and present are tied together in ways she doesn’t necessarily expect.”

“She comes to this town in Louisiana and is confronted with a series of occurrences that she can’t debunk,” adds Silver. “Suddenly, she’s in real danger and the tools she has come to rely on no longer work. The only weapon she has left is instinct.”

Fact, Fiction and Faith

The character of Katherine Winter is based on real-life skeptics and scientists that take on unnatural occurrences and miracles. “All over the world, people are drawn to the idea of miracles,” Silver comments. “Even when scientists try to explain them away, it usually fails to dissuade the faithful. It’s all part of the classic struggle between science and the will to believe.”

In preparation for her role, Swank delved into research and spoke to a number of debunkers, many of whom, like Katherine, were once very religious people. Swank notes, “I read a lot of books on debunking myths, and a magazine called The Skeptical Inquirer. I didn’t even know that there were magazines like that out there. I also read the Bible. It was so interesting to enter this world and see people driven by science and others driven by faith.”

Hopkins likewise plunged into the world of miracle debunking. “I met one gentleman who has debunked 60 or 70 miracles in his life, and he works as a professor of theology,” says the director. “He told me about his experiences going around the world. He’d seen a lot of things he could explain, but there were some things that he couldn’t. I think it’s an extraordinary type of character: someone who is obsessed with finding out the truth of whether these miracles exist or not.”

On Location

To find the ideal setting for the story, the filmmakers turned their sights on Louisiana. “Louisiana is an extraordinary place with such beautiful architecture,” Hopkins says, “and it still has a bit of mystery to it. We needed that for Haven, which is modern-day but still pretty cut off from the rest of the world.”

Locations manager Peter Novak led the filmmakers to their Haven – St. Francisville (pop. 1,712), a town, he says, “with beautiful scenery, a collection of spectacular Victorian homes, and a community of cool, eclectic people.” “Atmospherically,” Silver adds, “the place was perfect with its crumbling plantation homes, swamps, deep woods…”

The town’s history even lent itself to the story. Hopkins explains, “It was destroyed by floods about 120 years ago. There are lots of photos in the town museum, and we saw pictures of these places all underwater. After the town was destroyed, everything was moved up on top of a hill away from the swamps, and I thought, ‘I wonder if people lost faith living in those times?’ So, we modeled our town of Haven after St. Francisville.”

The local communities were welcoming and generous, but nature was another matter. The summer heat, which Hopkins admits, “could be staggering at times,” nevertheless worked to create a rich on-screen mood. Shooting was proceeding on schedule, with every element locked firmly in place…and then Hurricane Katrina struck. Herb Gains, who had been on location earlier in the summer and faced a similar hurricane threat, had already devised an evacuation plan with the Head of Safety at Warner Bros.

“When it was obvious the storm was coming our way, we got 120 people out,” Gains remembers. “We were the last flight out of Baton Rouge. But we left a few people there on the ground just to monitor events and help get things restored in the event we were able to come back.”

Only two weeks after Katrina, Hurricane Rita posed another serious—but thankfully short-lived—threat to the production. The locations had sustained mostly minor damage from both events, but many on the crew had suffered personal losses.

Gains recalls, “The first day back was quite emotional. People were breaking down. But I think the general sense was that staying and being a part of the region’s recovery effort was the right thing to do.”

“These people define southern hospitality; they were so welcoming and generous to us,” Swank offers. “They just opened their arms to us. Obviously, being here through two hurricanes and seeing the mass devastation that it had on this state was heartbreaking but also inspiring. To see these people lose their homes, lose family members, lose virtually everything, you are reminded of what’s important: ‘I’m alive. We’ll rebuild.’ It was amazing to see these things unfold. We were all so grateful.”

“It was strange to be working on a film that has so much to do with God’s work,” adds Gains, “and then be faced with God’s work in a very real way.”

Sowing “The Reaping”

In the center of the production’s base in St. Francisville, acclaimed production designer Graham “Grace” Walker supervised the installation of a gas station, mortuary and barber shop. “We found this little crossroads with two existing buildings and we built onto it,” he describes. “I’d never been to the South before and I just loved everything I saw, especially this great town.”

Whether designing for a small southern town, a gothic plantation, catacombs beneath an ancient site, or a desert in Africa, Walker and his team of artisans sought to adhere to the realism that colored every aspect of the film. Walker credits location manager Novak with helping to discover so many richly authentic sites for the film. “A place we called ‘Doug’s plantation’ was one of my favorites,” he says. “It’s an old, antebellum home — tremendous place. I loved it.” The set was fitting for a thriller drenched with mystery and surprise. Novak also found an old homestead on the swamp to serve as the McConnell house.

Academy Award-nominated costume designer Jeffrey Kurland (“Bullets Over Broadway”) worked with Walker and Hopkins to create a moody palette for the film’s costumes. “I chose tones that were very muted,” he notes. “There’s a patina to everything. I wanted to suggest a feeling of antiquity; everything looks worn and well aged and washed out, since one of the messages in the movie is that there’s a past to everything.

“For Katherine, I chose the style of tailored, workaday clothes,” he continues. “For Loren, we made a single dress for a girl a little younger than her age to support the plot. Slightly small and tight on her, the dress was aged to show the wear of the five days living in the woods that she endured.”

Elba’s character, a former street kid who had sustained eight bullet wounds, has an abiding faith in God—one that is expressed, in part, through his tattoos. “Stephen and I discussed extensively where we were going to place them,” Elba says. “And this guy has lots. In some scenes, only a few may be visible because of the clothing I wear. So those maybe took an hour and a half in the morning. But it would take a full day for the one on my back, which is a huge Jesus looking over a bridge. That one took a bit of patience.”

In a film that deals with the ten plagues of Exodus, the filmmakers sought to juxtapose the supernatural with a very real, believable world. Hopkins worked with his longtime collaborator, cinematographer Peter Levy, to give the visuals the immediacy of a television news report. “We decided to approach it in a photo-journalistic style,” Hopkins says, “which I think suits the way Hilary Swank’s character sees the world. She is very straightforward and evidence-driven, so I wanted this movie to have a very realistic feel to it.”

In the first plague, the river turns to blood. “It is red, yes, but it’s also full of dead fish and scum and looks polluted, like it could have been caused by an accident at a chemical plant, or something,” Hopkins describes.

The nine plagues that follow are frogs, flies, diseased livestock, lice, boils, locusts, darkness, fire from the sky, and the final plague: death of the firstborn. For the locusts, Hopkins wanted the sequence to convey the same feel as war footage shot by news cameras in the midst of a firefight. “The cameraman would be hiding behind a wall, so you only see certain things that happen,” he describes. “There’s dust everywhere, and you can zoom in on certain things and certain people. I used that approach with the locusts, where you feel like you’re amongst them. I have locusts splattering on the lens and things like that, so it appears accidental, but actually it takes a long time to make it look that way.”

The practical use of live locusts had a chilling effect on the entire cast and crew, all except young actress AnnaSophia Robb, who was required to interact with them on camera. “They were brought in a cage,” Robb recalls, “and for practice, to get me used to them, the insect wrangler would put them on my shoulders and knees. I held them and got used to picking them up. They’d put them on me at any given moment and I couldn’t flinch. Sometimes they even threw them on me and I had to be calm and still. They’re my friends now. I named a few of them; my favorites are: Big Boy Bob, Gloria and Elvis. They’re kind of scary looking, but unless you’re a piece of lettuce or something green, they won’t hurt you.”

Practical footage was then enhanced with computer-generated imagery supervised by Richard Yuricich, whose credits include the classic “2001: A Space Odyssey,” among numerous other projects. “We were lucky in that we had a master of visual effects,” Hopkins attests, “one of the founders of digital film, in fact. Richard is a legend.”

Hopkins did not want to stray from Levy’s earthy photography, so Yuricich worked directly with the negative rather than shooting separate effects plates. “It was a fun film for me because traditionally I’m involved in photographing elements independently and then compositing that footage with the live action footage,” Yuricich explains. “For this film, we treated the first element – the original negative – and tried to be as photo-real as possible in telling the story with these visuals.”

“It’s a challenge these days because studios are turning out movies faster and faster, and you want to make sure you get the CGI effects just right,” adds co-producer Mirisch, “especially in a movie like this one that has such a photo-realistic style.”

For all involved, it was important to ground the supernatural elements of “The Reaping” into the very real notions of faith and the loss of faith. “The film is about faith and spirituality, but it’s also about how, in any community, the theological power of religion can grow out of proportion,” concludes Hopkins. “As on any personal journey, spirituality and religion can enlighten you…but they can also be used to control people. I think the film deals with that duality in a big way.”

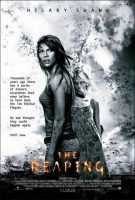

The Reaping (2007)

Directed by: Stephen Hopkins

Starring: Hilary Swank, David Morrissey, Idris Elba, AnnaSophia Robb, Stephen Rea, William Ragsdale, John McConnell, Yvonne Landry, Andrea Frankle, Samuel Garland, Lara Grice

Screenplay by: Chad Hayes, Christopher Markus, Stephen McFeely, Brian Rousso

Production Design by: Graham ‘Grace’ Walker

Cinematography by: Peter Levy

Film Editing by: Colby Parker Jr.

Costume Design by: Jeffrey Kurland

Set Decoration by: Chris L. Spellman

Art Direction by: Scott Ritenour

Music by: John Frizzell

MPAA Rating: R for violence, disturbing images and some sexualityR for violence, disturbing images and some sexuality.

Distributed by: Warner Bros. Pictures

Release Date: April 5, 2007

Views: 141