Tagline: Close your eyes. Open your heart.

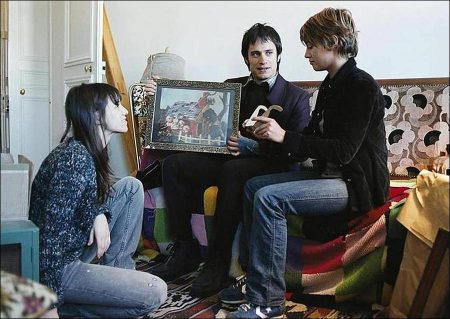

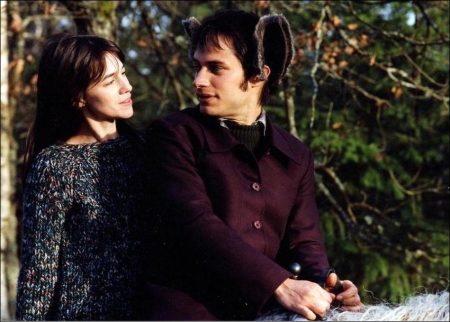

The Science of Sleep is a playful romantic fantasy set inside the topsy-turvy brain of Stephane Miroux (Gael García Bernal), an eccentric young man whose dreams constantly invade his waking life. While slumbering, he is the charismatic host of “Stephane TV,” expounding on “The Science of Sleep” in front of cardboard cameras. In “real life,” he has a boring job at a Parisian calendar publisher and pines for Stephanie (Charlotte Gainsbourg), the girl in the apartment across the hall.

While Stephanie is initially charmed by Stephane, she is confused by his childishness and shaky connection to reality. Stephane’s co-worker, Guy (Alain Chabat) a vulgar but practical man, offers advice on the opposite sex, but Stephane is too far in the clouds to listen. Unable to find the secret to Stephanie’s heart while awake, Stephane searches for the answer in his dreams.

Written and directed by Michel Gondry, the boundlessly inventive creator of award-winning films (“Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind”), videos and commercials. “The Science of Sleep” is a whimsical trip into a cut-and-paste wonderland fashioned from cardboard tubes, cellophane, and imagination.

Interview with Michel Gondry

Your award-winning movies, music videos and commercials have been seen by millions of people, yet this is your first feature film from your own screenplay. Why do you think it took you so long?

I don’t think I had the confidence yet. But as I went along and did more work, I realized I had things to say and wanted to go deeper into expressing my own voice. I’d always been expressing my voice alongside somebody else’s, and felt the need to put more of myself out there.

With the videos, most people never really understood what I wanted to do until they gave me a chance to do them. And then afterwards, they generally liked it, and I really had a good amount of freedom. But in film it was different; it’s a much heavier medium and I needed to justify everything.

One of the reasons I really wanted to do “The Science of Sleep” was not to have to question my ideas on an intellectual level. When I work with other people, I have to use words. It’s more limiting to the process to have to convey my ideas that way. If you want to create something, hoping it will go beyond yourself, you can’t question every step of the process. It may seem contradictory, but the fact that I’m the only one to make the decisions allows me to have less control of things. I want my instinct to be more in control and my intellect to be less in control, allowing me to have ideas, images, and concepts without having to justify why.

“The Science of Sleep” is extremely autobiographical: among many other things, it was filmed in the same building you lived in Paris while you were working a boring job in a calendar company.

I drew a lot from my own experiences. Even if I go in a lot of different directions, Stephane is obviously a certain perspective of myself. But not just Stephane, I am in other characters as well.

Often when actors play a character inspired by their director, they do an imitation. Gael doesn’t do that.

It’s a midpoint between my idea of the character-obviously myself-and who Gael is. I think if you don’t do that, it’s going to be a little fake. He has to think all the time that he has to add this layer. To me, the magic of making films is creating something new by combining different personalities. It’s really important for me that I take a lot from the personality of the actor. To me, it’s very important to let people be free.

Many of the images in the film have been seen before in your music videos.

Maybe it was the other way around. This story has been marinating in my brain for a long time. Maybe in the videos I was already using stuff I wanted to use in my film. I think that even if I didn’t try those images before I still would have used them in the same way. It’s all part of me.

Stephane has your creative gifts, but he hasn’t been able to make them work for him in the real world, as you have.

I think many artists spend a lot of time developing their skills to compensate for their inability to reach out. You want to make an object that is an intermediary between you and someone else, instead of directly talking to them. You want people to take notice of you, and ultimately, you want to find a girlfriend.

Basically, when these artists are out in the world trying to find a mate, also out there are the people who didn’t waste their time being artists. So they are out on the market, getting all the girls before you. It’s what happened to Stephane.

He makes these great things for Stephanie. But he’s so into his own world that when he tries to be with her it doesn’t work. She has a down-to-earth quality that makes his neurosis a little scary for her. You can see their difference when he says that the glasses allow you to see real life in 3D, and she says, “Life is in 3D already.” She’s more aware of what’s out there, and he’s more inside, more oblivious.

Charlotte Gainsbourg seems an apt choice for Stephanie as she had a very suggestive, controversial upbringing as the daughter of Serge Gainsbourg and Jane Birkin. One could say that in her life she was the opposite of Stephane-a child’s body with a woman’s mind.

It’s an interesting point. She was born into the world too early in some ways. Her mind was mature but her body seemed to be behind her. I think it’s probably part of why I was drawn to Charlotte for this character. But there’s a childlike quality to her too. She still has the same genuineness. She seems transparent and not really trying. There are very few actors who can convey that-to just be in the moment without having to put on an act or a face. She’s very receptive to what’s happening around her.

When you were making the movie, did you always know what was meant to be a dream and what was reality?

Sometimes it might not be clear in the film but I always knew because most of the dreams in the film were ones I had myself. There is one thing that might seem confusing but I knew when I was doing it. Sometimes in real life there’s a little bit of dream life. Like when they throw the cotton and it sticks on the ceiling like a cloud. It’s a moment they share. They both pretend they see the same thing. And we are where we feel what they are feeling. That’s why we see it too. It’s reality at that moment.

“Stephane TV” is like the toll booth that Stephane goes through in his travels from dream to reality and back.

I had this idea for a long time and I thought it was a nice way to bring people into his head. In your dreams, your eyes don’t see what’s going on in front of you so I put in the window and the curtain in the back. That’s inside his head, going deeper into his dream. I used blue screen here. And it’s kind of humorous because the blue screen is something very technical, very mundane. It’s not magical at all. It’s comic for me that you can create your own world with a blue screen and some buttons. I thought it was a nice way to go from one world to another.

You tend to work with effects in two ways. Sometimes it’s technologically astounding: it makes you wonder how it was done; and sometimes it looks like an idea a clever child might have come up with.

I’m aware of both sides. I’m aware that sometimes people can be really amazed by the precision of the technology, but on the other hand, I like it to be naïve, handmade and crafted. It’s a combination. But it’s hard to maintain that in a film. There are so many people involved and everybody tends to polish everything.

There are a lot of things we see in animation where it’s so perfect you can’t see the difference compared to CGI. It’s so detailed and perfect. When people try to be too good it’s detrimental to the spontaneity.

I’m a very good animator, and when you look at some of the backgrounds in “The Science of Sleep,” they’re really detailed–but there’s an intentional clumsiness to the way they’re conceived. I wanted to be sure we preserved this handmade quality in the movie.

You made all the animation ahead of time. How long did the process take?

Five years ago, I bought my Aunt’s house in the mountains. At one time there was a saw-mill there. All the equipment was gone; it was just a bare warehouse. It’s pretty small, but we transformed it into a mini-factory for animation.

We shot all the animation for “The Science of Sleep” with a crew of about ten people over the course of two months. We got a lot out of those two months – it cost nearly the equivalent of adding a week to the budget if we had the full cast and crew working, which is still quite a lot of money – but the effort was worth it. We created the dream world before we began shooting the film, before the story was fully completed. During the shooting, I had to work around the dreams, rather than the other way around. It made the film more interesting, because it wasn’t done in the typical way where the dreams follow the arc of the story.

When you were shooting, did the actors see the animation?

Yes, it’s very important to me. When we used the blue-screen in “Stephane TV,” we did it live, so you could always see what was going on in the TV monitor. Most of the time, I use back projection, which is a very old technique. It’s very difficult to do, but it gives a good vibe on the set. “Oh look what we did in my country house animating toilet paper rolls! We did a city and everything is moving!”

The actors are like kids watching something they enjoy. It gets everybody on the right tone. I think movies that have blue screen always seems a little dead to me. You can see that they’ve been shot on a separate element, and then matched together

When Gael flies, we used this big tank, and he swims in front of a back projection screen. I don’t think many people would conceive an effect like that now. They’d probably use bluescreen or wire work. It was very complicated to do it this way, but it gives it a grace. Flying has been done so many times in the movies-you need to find a different way to do it.

Stephane is really hard on Stephanie at the end. You see a crudeness in him that you’ve never seen before.

He’s just lashing out. But we see before that he likes to say inappropriate things at the wrong time. It’s like a contradiction with his shyness. Like Tourette’s Syndrome. I think Stephane has a bit of that, this thing that he can’t stop himself saying something stupid. It comes out full blown at the end. It’s his madness.

Maybe unconsciously or consciously, I pushed this side a little further because I was afraid people would not understand why a girl like Charlotte would not be attracted to a guy like Gael. One of the reasons is he’s a little insane. I think insanity is unattractive. Being down-to-earth is a more attractive quality for women.

Like “The Science of Sleep”, your films “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind” and “Human Nature” are also about people caught between different worlds. Why do you think you’re attracted to this theme?

I remember I was fascinated when I was a kid, because I lived on the edge between the forest and the city. I was very intrigued by the transition between one world and the other. When you go into another world, you feel like you’re on another planet and maybe something unexpected is going to happen any second. When you walk into Stephane’s dream, he is in reality but in his world seems on an alternative level. You don’t understand that. So maybe it’s why I like it.

Another recurring element in your films are things that turn up in an unexpected context-like the forest in the boat or the bathtub in the office in this film and the bed on the beach in “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.”

Maybe it’s an influence from the surrealists or some other artists, but I think when you dream you have a lot of misplacement of things.

Your brain is usually in a passive world that’s coherent. But when your brain sees something that doesn’t match, where there is incongruity, it has to work very hard to reconstruct everything. Because it’s not something you’re used to seeing, it makes you question your reality. It’s a very creative moment.

In your dream there are a lot of fantasies in your head and the brain recreates the continuity. So the bed out in the beach in the snow in “Eternal Sunshine” contributes to that state of mind where everything’s not normal. And this is something that I like to do.

Do you really believe there is a Science of Sleep?

I totally believe that. What I don’t believe is the mythology and the symbolism of dreams. I don’t see why everybody should have the same associations. I think every one of has can have their own associations. Maybe there are general associations, but the idea that you can have a dream about a snake and then pick a dictionary for an explanation doesn’t make sense to me.

I think it’s much more simple. You’ve got to explore your memory. You’re going to see that you’ve been in contact with a snake in a context that was recalled in your dream.

And it’s much more interesting to me this way. I feel like I’m looking at the map of my head and it’s everything I’ve experienced since I was born. It’s all inside there. So every day, I dive into a big sea of all the events of my life. It’s just amazing.

Like the big stew that Stephane stirs up in the first scene…

Yes. I think it’s good to think of dreams in these terms. I’m happy to remember a dream and see maybe what’s on my mind. But I don’t think it really tells me who I am-it’s just an exploration. It doesn’t give me an answer like going to see an astrologist to be reassured:

“You’re going to be fine” or, “You’re going to meet somebody.” It’s more personal. I think science is more fun than mythology. People like things like astrology so that they can believe in an invisible world. But there are a lot of invisible worlds in science too. Who has seen a proton?

The Science of Sleep (2006)

Directed by: Michel Gondry

Starring: Gael Garcia Bernal, Jean-Michel Bernard, Emma de Caunes, Charlotte Gainsbourg, Stéphane Metzger, Miou-Miou, Aurélia Petit, Pierre Vaneck, Alain Chabat

Screenplay by: Michel Gondry

Production Design by: Ann Chakraverty, Pierre Pell, Stéphane Rozenbaum

Cinematography by: Jean-Louis Bompoint

Film Editing by: Juliette Welfling

Costume Design by: Florence Fontaine

Music by: Jean-Michel Bernard

MPAA Rating: R for language, some sexual content and nudity.

Distributed by: The Weinstein Company

Release Date: September 29, 2006

Views: 57