The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Beginning. “The fans wanted another Chainsaw, it was that simple,” says Bay. “But then again, it wasn’t because we cut off the bad guy’s arm at the end of the first one. So the storyline was definitely a challenge, but once we decided to make a prequel rather than a standard sequel, the possibilities were endless. We just had to keep ourselves in check and not go too far out there.”

Brad Fuller adds, “Andrew and I sat down with Michael and discussed whether or not the family’s story was compelling. Is being a family of killers enough of a base on which to build a movie? We knew the first step was finding a writer to help flush out the details.”

The filmmakers contacted Scott Kozar, who penned the 2003 remake, but he was tied up with other commitments, so they immediately turned to Amityville writer Sheldon Turner. To get things rolling, the producers gave Turner a copy of the 2003 film and asked him not only to come up with some ideas, but also to come up with answers to questions posed by the original story, such as: How did this family become the people they are? Why is Uncle Monty a double amputee? Why does Hoyt have no teeth and how in the world did he become a sheriff? And, of course, why does Leatherface do what he does, and what’s up with those horrific skins he wears?

The producers were thrilled with the answers that Turner devised and shortly thereafter found their director in Jonathan Liebesman. “We hired a great writer,” says Fuller. “When the script came in as strong as it did, we knew we were prepared to make it, so we went to Jonathan early on. The meetings started, Jonathan made a presentation and showed us how he planned to elevate the screenplay, and that was all we needed to hear.”

The Platinum Dunes producers first met director Jonathan Liebesman in 2002 when they were interviewing a short list of directors for the first The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, but Sony snatched Liebesman away to direct Darkness Falls before they’d finished reviewing the candidates. They kept in touch and called him again for Platinum Dunes’ second venture, Amityville Horror, but instead of Amityville, they earmarked his talents for their next stab at Texas Chainsaw. Although he has the enthusiastic support of the producers, Liebesman was not certain about taking on the film until he discovered that his concerns about another Chainsaw project were the same as theirs.

“Making a sequel to such a great movie, especially one in which the principal antagonist has lost his ability to be menacing, was not especially appealing to me,” explains Liebesman. “But exploring how this legend began was much more interesting. As a fan of the first movie, I wanted answers to the questions it posed. In my first meeting with Michael, Andrew and Brad, I basically laid out what I thought the movie should be and mentioned ideas I would like to see included in the script. At the end of the day, we had the same vision: the movie needed to feel like the beginning of hell.”

Andrew Form adds, “The main idea for doing a prequel was to show how the killer, Leatherface, came about. You see the rage build in Thomas Hewitt, you watch it take over, and then you see this sad man kill another human being for the first time. As Thomas falls deeper into Hoyt’s clutches, Hoyt takes on the role of puppeteer and begins manipulating him in the most calculated and heinous way.”

Once they decided that making a prequel was the way to go, the filmmakers had to decide exactly how far back they wanted the story to go. “The movie opens in 1969, about three years prior to the time of the original movie,” says Brad Fuller. “The town is built around a slaughterhouse which has been condemned and is going out of business, and with it, so goes the town. Thomas Hewitt loses his job, along with everyone else, and his anger that’s been on a slow burn since childhood propels him to make his first kill, which compels his already unstable uncle to take the law into his own hands and wreak his own havoc.”

”At the same time, a group of kids, who are dealing with their own conflicts, are driving across Texas, and through a terrible turn of events, find themselves in this horrible town,” continues Fuller. “When the kids encounter the Hewitts, the family is on a slippery slope of killing one person after another in order to cover up the previous murder, and it just spirals out of control.”

With the back story in place, filmmakers still had to make some decisions about how best to present it in the film. “The most difficult thing about working in the horror genre is trying not to demystify the mystery, because when you explain evil or show too much of it, it’s no longer scary,” says Jonathan Liebesman. “It’s a fine line in trying to illustrate the irrationality of serial killers – one doesn’t want to explain too much or rationalize their behavior to a point where it’s no longer mysterious. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Beginning is just that – it’s about the day the killing began, but not necessarily too much of why it happened.”

In discussing the viability of a prequel, one of the first items on the filmmakers’ list was the issue of casting. Who would be returning from the previous movie? Andrew Form likes to say that his producing partner, Brad Fuller, takes charge where casting is concerned. They began with the strongest link in their Chainsaw chain, R. Lee Ermey.

“Unfortunately, horror movies get a bad rap because some of them cop out and don’t strive to get the best actors,” says Fuller. “When we cast Lee, he was a mark of quality and hiring him allowed us to surround him with people who were similarly talented. We didn’t wimp out and go with clichés. We wanted to find true actors who could bring something to this family. They are the root of the interaction between all the characters and the audience has to believe them.”

Form adds, “Lee has his own theories about who his character is. He is an actor without boundaries. He’s said to me on numerous occasions that he wants Hoyt to be the most politically incorrect person there is, and so he finds himself striving to figure out who else he can offend. There isn’t anyone who’s safe.”

As a result, Ermey’s performance is one of the highlights of the film. “Lee is one of the most entertaining parts of the first movie,” says Jonathan Liebesman. “His character is insane, and at first makes little sense, but that’s what makes him so interesting, because there is no explanation. He’s a mystery. Lee, himself, was very helpful in exploring and molding his character.”

“He adds such humor,” agrees Michael Bay. “Whenever you do intense horror movies, it’s always good to have a comic release, especially when the audience is really tense. So while Lee’s performance was very real, it was also bizarre and even a little funny all at once.”

Ermey is quite passionate about his contribution to Sheriff Hoyt. “It bothers me to think that as an actor, I am simply a puppet, that somebody puts words in my mouth and pulls the string and makes me move,” says the veteran actor. “I think it’s an actor’s obligation to make suggestions and to make the script better. As I see it, the writer is spread pretty thin, but I’m only concerned with one character. I like to be off-the-wall, shocking, colorful. And let’s face it; Hoyt is a sexually perverted homicidal maniac. Now, how can you take that over the top? With Hoyt there’s no limit. I would classify Sheriff Hoyt as the most dastardly character I’ve ever played.”

The filmmakers knew that Ermey was coming back to the fold, along with Marietta Marich as Luda Mae and Terrence Evans as Old Monty, not to mention Kathy Lamkin as the Tea Lady, but also crucial to the mix was the return of Andrew Bryniarski, who plays Leatherface and has established a cult following all his own since appearing as the masked murderer.

“These actors have been living with their characters for a long time,” Liebesman says. “They had a lot of suggestions for things they didn’t get to do three years ago, and we gave them enough time to explore that. Some of the stuff is great, some is bizarre, and some didn’t make it into the film. But because in 2003, director Marcus Nispel made a movie packed with texture and atmosphere that comes from the actors being in the surroundings and being allowed to improvise, each of them already knew what he or she wanted to add.”

“Marietta, for example, has been acting for about 50 years,” continues Liebesman. “An actor who has been working that long has a lot of really good ideas: singing to Bailey in the midst of her torture, which is one of the creepiest moments in the movie, and playing with a tongue while she makes dinner – weird, crazy stuff that none of us would have thought of, which was surprising for a dignified woman of her age.”

A seemingly innocuous character, Luda Mae has a definite role and position in the Hewitt family hierarchy. “She is the only one who can keep Hoyt in line,” Liebesman explains. “He’s an egomaniac and thinks he rules the world, but when he goes crazy, Luda Mae is there to remind him that even though he kills and eats people, he must mind his manners at the dinner table.”

“Luda Mae is the matriarch of what I like to call the `killer brood,’” says Marich, who auditioned for the part by donning an old robe of her husband’s, not combing her hair, and pretending to chew a wad of tobacco by letting chocolate run down her chin.

“I always make up a personal history of characters I play, so I suspect that Luda Mae was a homeless young woman who had to make her own way during the Depression,” Marich describes. “When she finds Thomas, she takes him home, even though he’s disfigured and hideously ugly, and protects him as much as possible from the cruel people he encounters and the world at large. That’s her main purpose, and the only reason Luda Mae sticks around.”

Unlike Luda Mae, Monty’s quiet nature does not belie hidden confidence or any fervent convictions. According to Liebesman, Monty is “the lackey of the family. His job is to keep the junkyard full of rusty paraphernalia. He’s the maid, the brother that never got out, the ne’er do well, but he also serves as a device for Leatherface to practice the art of sawing flesh and bone.”

Actor Terrence Evans defends his character. “Monty is practically an innocent, not totally, but certainly more than Hoyt or Thomas,” he says. “I see Monty as a secondary character because Hoyt really drives the scenes, and my role is more reactive. Nobody ever asks Monty for his opinion, not even when Luda Mae brings Thomas home, so he just goes with the flow and endures whatever’s thrown his way.”

“I think there was a chance Thomas’ life could have been different,” Evans continues. “But the teasing he suffered, coupled with a bad temper, and following Hoyt around like a puppy dog, left room for Hoyt to get absolute control. So Hoyt becomes the daddy and I take on my role as uncle.”

In The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Beginning, Leatherface is far from a one-note character; it is a surprisingly involved role, difficult to portray given that the actor cannot speak to convey his emotions, desires or needs, and must rely solely on body language and eye movement.

“It’s harder to act when you cannot speak,” asserts producer Andrew Form. “Gestures and movement can easily translate into overacting, so there is a fine line when the actor has a lot to convey. Andrew Bryniarski is particularly good at finding the middle ground because he knows the character so well. He is Leatherface and he takes his role very, very seriously.”

“Let’s face it, the guy’s got a social phobia,” says Bryniarski. “He suffers from some real anxiety due to people being mean to him his whole life, which changes him at a certain point and after he’s taken enough, he becomes the person responsible for a chainsaw massacre.”

Because so many people identify Bryniarski with Leatherface, he maintains he must work harder to be a nice guy in order to play down the image of the serial killer. “I’ve played a lot of crazy characters very convincingly over the years, so I am used to people keeping me at a distance,“ he says. “But I knew I had to do this role. As Michael Bay likes to say, `I was born to wear the mask.’”

The truth is, he tore it up in my office,” jokes Bay. “That’s the true Hollywood story! He was genuine and kept telling me, `I am that guy!’ Seriously, how can you turn down that kind of sincerity?”

A question that might never be answered in any installment of the series: How are the Hewitts related? Everyone on the show – cast and crew alike – had a different opinion. During breaks between set ups, it became a game to see who could come up with the wildest story for the threesome.

“We never decided how they’re connected,” confesses producer Brad Fuller. “We think it’s more interesting to leave it alone. Why does Hoyt call Luda Mae, a woman who is obviously a bit older than he is, `Mama?’ There’s no way she could be his mother. It doesn’t make any sense. And Monty, is he Luda Mae’s husband? Or are he and Hoyt brothers? Just the thought makes the whole dynamic unsettling.”

Terrence Evans has his own theory. “Luda Mae is my sister and Hoyt is my brother. Hoyt didn’t get all the brains in the family, but he sure got all the meanness. So whatever Hoyt says, that’s what we do.”

“We all have our own theory,” laughs Form. “I don’t even know if we agree.” The Hewitt family is both funny and bizarre, but given the goal of creeping out the audience, the family dynamic works. And as a family, they take in a deformed, motherless infant who, under their care and nurturing, becomes a blood-thirsty killer.

“They raise him as their own,” says Fuller. “But in a lot of ways, Thomas Hewitt is more like a pet than a member of the family. At the same time, they do love and admire one another, albeit in peculiar and unusual ways.”

“You never know what another family is like until you live with them,” he continues. “You see them out at dinner, you enjoy their company at social events, but you really don’t know what goes on in anyone’s home. We thought it would be compelling to show what goes on inside a really screwed up home. But what’s most bizarre is that the Hewitts don’t think they’re abnormal. When you walk through their door, it’s their rules and nothing else applies, and ultimately, anarchy prevails. That’s why this is scary, because that can happen anywhere. You never know what goes on behind your neighbor’s door.”

Instead of taking the easy route and making a commentary on physical appearance and its social ramifications using Thomas Hewitt’s deformities, the filmmakers focused on the Hewitts as a case study in family relationships. “What makes a family a family?” poses producer Brad Fuller.

The shift in focus from the kids in the 2003 The Texas Chainsaw Massacre remake to the Hewitt family in the prequel will not only allow audiences a chance to get to know the family better, it is a device that will hopefully ingratiate viewers to a new group of young actors playing the innocent, unsuspecting victims of circumstance. The producers like to think of these characters as “the audience proxy.”

“The kids who are trapped in this terror are the people the audience will relate to,” explains Fuller. “The emotions they are feeling are the emotions we hope the audience feels, so we had to find compassionate people to play those parts. The audience needs to associate with them and root for them. We tried to find the best, most believable, sympathetic young actors who you could watch and say, `I would do exactly what they’re doing.’ That’s the root of good horror.”

Director Jonathan Liebesman adds, “My favorite characters in horror films are always the ones who want to be strong even though they’re as frightened as you and I would be. All the characters in the movie are questioning their own courage. It’s not about whether they cry or not, whether they’re strong or really cowards at heart; what’s important is that the characters try their best to save each other. And Jordana Brewster, who plays Chrissie, the lead protagonist, comes across as exactly that type of girl.”

Brewster was the first member of the new cast to be hired. As Chrissie, she plays a young woman who is devoted to her boyfriend, Eric Hill, and their relationship. When she discovers Eric’s plan to re-enlist, she remains steadfast and supportive despite her fear that he won’t make it home. Chrissie also knows that even though she might have reservations about his decision to return to Vietnam, Eric’s sense of honor and responsibility confirm the kind of person he is, the kind of man she loves and admires.

Once the kids find themselves fighting for their lives, Chrissie never wavers in her quest to save the other three. “She is vulnerable and afraid, and every time she moves to help someone, you can see her doubt,” says Liebesman. “Like Sigourney Weaver in Aliens or Jodie Foster in Silence of the Lambs, Chrissie is completely frightened of what’s behind the next closed door, but she will walk through it anyway. That’s a hero.”

Both Brewster and the filmmakers understood that Jessica Biel set the bar high in her portrayal of Erin in the 2003’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. “We got Jessie just as her career was taking off,” says Michael Bay. “We were lucky because she’s not only talented and dedicated, she’s an actress who really likes her job and wants to do whatever she can to make the project better as a whole. She’s generous with her fellow cast and just an all-around nice person. And even though she and Jordana are very different in many ways, we lucked out again because Jordana has those same qualities.”

“I don’t think people are prepared for how smart Jordana is,” Bay continues. “You can’t help but focus on her beauty, but then you talk with her and you’re bowled over by her intellect and her interest in everything and everyone around her. She’s experienced in the horror genre; she knows her stuff.”

For Brewster, the key to the role was to portray her character as being different from the typical overwhelmed young woman that is often seen in these kinds of films. “Jonathan and I tried to strike a balance between Chrissie being a complete heroine who unrealistically faces a 300-pound Leatherface versus a girl who’s a damsel in distress, which is really irritating to watch,” she says.

“When she hits the point where she’s basically lost everything that matters to her, she strikes back,” continues Brewster. “I had a scene with R. Lee Ermey where Hoyt justifies what his family is doing to Chrissie and her friends – he calls us sinners. That got to me; it really pissed me off, so I used that in terms of not surrendering and not wanting to be one of the Hewitts’ victims.”

Next to be cast was Diora Baird as Bailey. Beautiful, free-spirited yet determined, Bailey convinces her boyfriend Dean that he could never survive being a Marine and that his only hope of happiness is following her to Mexico, far away from the insanity of war.

Baird describes Bailey as “sassy, and very much a hippie of her time, everything for peace and love. She’s a hopeless romantic, but on the other hand, she doesn’t take crap from anyone, even the Hewitts. I like this character because she’s got an edge. Even when she’s in pain, she gives her captors a piece of her mind.”

“Bailey is a firecracker,” agrees director Jonathan Liebesman. “In any other horror movie, she’d be the pretty, dumb girl, but we wanted to give her a bit of spice.”

The filmmakers purposefully looked for a counterpart to Chrissie – although both are beautiful, Bailey and Chrissie are very different. “Chrissie is erudite and contemplative while Bailey is more simple and free spirited,” says Brad Fuller. “When Bailey is scared, it’s amazing because the fear is palpable. Watching Diora in these terrifying situations, listening to her scream, is very unsettling.”

Liebesman, who asked the actress to scream continuously after hearing her give an impromptu shriek while filming a torture sequence early on in production, also heaped praise on Diora’s work. “She has an Energizer bunny of a scream,” he says.

“I never even screamed for the audition and I don’t think it was in the script,” says Baird. “But once I screamed, Jonathan asked me to keep screaming. After a while, it did take a physical toll, but I just hope I don’t make the audience crazy,” she laughs.

At 21, Taylor Handley is the youngest cast member in the production. His audition tape was so incredible that the filmmakers offered him the role of Dean without ever meeting him face-to-face. After Brad Fuller saw the tape, he called Andrew Form, who was scouting locations in Austin, Texas, to express his excitement at discovering the actor. When Michael Bay saw the taped reading, he immediately concurred.

“Usually we bring people back five or six times, but Taylor never saw the inside of our office,” says Fuller. “He’s very young and doesn’t have a huge depth of experience yet, but he’s immensely talented.”

The ease with which Handley landed the job speaks to his relaxed personality. Warm and affable, he was a favorite on set, one of those people that everyone likes. Nonetheless, Handley’s emotional range will surprise audiences.

“Dean is an artist and a lover,” Handley says of his character. “He’s very innocent and not all that knowledgeable about Vietnam, but he knows it’s not his scene.”

“Horror movies are a genre I like very much,” he admits. “It allows actors to go to a deep, tormented place somewhere in their soul and bring up all this stuff that you normally don’t get to in a teen movie or a drama. In a horror movie, you’re screaming your lungs out, running, tripping and falling, and you really do get a feeling of sheer panic when some guy with a chainsaw is chasing you. Even with the crew standing around, you have to get into the moment, because that’s the fun of it; just to feel that rush.”

The role of Eric Hill was the most difficult to cast. “Finding a guy who is tough yet sympathetic is hard,” says Fuller. “We wanted someone who looked like Taylor, but certainly, at the end of the day, the acting ability is far more important.

“We asked Jordana to come in and read with ten actors a day,” Fuller continues. “We did that for about a week. And when Matt Bomer came in, you could just feel the chemistry. You could see that Chrissie was in love with Eric and Eric was in love with her. Matt was also able to convey the feeling that he’d been in Vietnam.”

A graduate of Carnegie-Mellon University’s prestigious drama program, Bomer prepared for the film by watching several movies about Vietnam and reading Born on the Fourth of July to give him “a detailed account of what is was like for someone injured in the war, having to come back home. It was a good starting point in terms of preparing to play Eric, to understand the sense of alienation these guys go through, while trying to keep everything together.”

During production Bomer also used R. Lee Ermey as a research source. “I spoke with R. Lee pretty extensively,” Bomer says of the former Marine. “He was very helpful anytime I had a question.”

After Matt Bomer’s audition with Jordana Brewster, Michael Bay turned to the actress and asked her, “Did you like him?” Her response was simple, “I loved him.” And that was it; the foursome was complete.

Rounding out the non-Hewitt family cast in small yet pivotal roles are Lee Tergesen as the biker, Holden, and Cyia Batten as his girlfriend, Alex.

With the core cast members on board, filmmakers turned their attention to developing the chemistry between them. “It came together fairly quickly, compared to other movies we’ve done,” says Fuller. “And the overall chemistry of the kids was tested with the first week of the movie because the first scenes between both couples were the more intimate sequences. The movie sinks or swims based on the audience’s ability to believe they care about one another.”

After watching all the dailies from Marcus Nispel’s 2003 The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, director Jonathan Liebesman was particularly struck by the dedication of the actors. He soon learned there was a Platinum Dunes method for establishing the bond between cast members.

On The Texas Chainsaw Massacre the filmmakers made sure Jessica Biel, Jonathan Tucker, Erica Leerhsen, Mike Vogel and Eric Balfour spent significant time together before a frame of film was shot. The results of that effort were so positive the filmmakers were adamant about repeating the exercise with their new cast and have since adopted it as company policy.

“It’s very important to take the time for something like this, especially when the characters have a solid connection, bonded by lifelong friendships or strong relationships,” says Michael Bay. “Sometimes it takes weeks to get that kind of genuine feeling between actors, so I’m pretty adamant that we get people hanging out together early on so that they can start to become friends and get to know little nuances about each other. It makes the group more cohesive.”

Brewster, Baird, Handley and Bomer joined the filmmakers in Austin, Texas two weeks before principal photography. “We all spent a lot of time together,” explains producer Andrew Form. “Not rehearsing, but going to lunch and dinner, seeing movies, shopping, going out at night, spending some quality time, just so that everyone could get to know each other. We’ve been lucky that the bonding we encouraged made a difference on screen.”

The Sunday before cameras rolled, Bay, his partners and director Liebesman took the young cast members out to the Hewitt house – the same house used in the 2003 film. Built in 1854, the house sits on a 750-acre farm in Texas. Vacant since the 1960s, the house remained untouched since the film company last shot there in September of 2002. Happily for the producers, it had lost none of its creepiness. This time around, audiences will be able to see more of the property, including the upstairs bedrooms, a small, detached garage and acreage surrounding the house, all of which were not used in the first film.

“We gave the actors an initial tour, and then Michael, Brad and I went off and discussed some scenes and let them walk around by themselves and explore and get the lay of the land,” says Andrew Form.

“Going there without crew, without lights and equipment and 100 people running around and all the distractions really set the tone because it’s such a spooky place,” he continues. “That house has a history and you feel it when you’re in there. Filming at the house just elevates the material.”

After the first movie, fans sought out the house, prompting the owners to call local authorities from time to time to get people to leave the property.

Another favorite location to which the filmmakers returned was an 1887 cotton gin 45 minutes south of town in Martindale. Used as the Hewitt basement as well as the slaughterhouse, the location offers both exterior and interior possibilities. It also afforded the cast and crew a beautiful, peaceful spot on the water (where the opening lake sequence of the first film was filmed in 2002) to sit and breath between constant takes of torture and pain.

“You take off the headphones, walk down to the water and remind yourself that you’re just making a movie,” Brad Fuller laughs. “It’s a beautiful location and we just couldn’t bear going back to the actual slaughterhouse we filmed in on the last show.”

“We put Jessica Biel in a real meat freezer and that was tough because the entire place smelled,” explains Andrew Form. “It was hard on everyone and we didn’t want to put people through that again. Besides, the place looked too modern and this film opens in 1939, so we needed to create a slaughterhouse from that period that we could transform into a rundown, rickety version 30 years later when it goes out of business in the late 60’s.”

To create the look of the film, Marco Rubeo, the son of eminent production designer Bruno Rubeo (Driving Miss Daisy), was moved up the ranks from art director to production design his first major motion picture. The producers recognized his talents after he acted as the art director on The Amityville Horror and thought it was the right time for Rubeo to step up to the plate. Not only did Rubeo have to replicate many of the sets from the 2003 film, he also had to take them back in time a few years, making slight yet noticeable changes, as well as create some of his own, new sets.

The filmmakers gave Rubeo and his design team, as well as director Jonathan Liebesman and director of photography, Lukas Ettlin, copies of the DVD of their first film to study the locations and the overall look of the movie. They needed their new team to take over where director Marcus Nispel, cinematographer Daniel Pearl and production designer Greg Blair left off – a big challenge to be sure, given the many accolades the 2003 film earned.

Once Jonathan Liebesman had been hired, discussions began about who to hire as the cinematographer. He was quick to ask for his good friend and long-time associate, Lukas Ettlin, who had shot every student film Liebesman made, garnering both of them numerous awards over the years.

Form and Fuller readily admit that his request was not taken all that seriously at first. “We laughed,” confesses Fuller. “We told him, `That will never happen, so get the idea out of your head.’ It was a stretch to give a director who has only made one film a DP who’s never made a major movie, but Michael Bay was not as worried as we were. It just seemed like a very challenging and demanding proposition.”

“We sat down with Lukas and found that he had a great take on the film,” Fuller continues. “He understood the look we went for in the first film, but at the same time, he wanted to make this movie his own. Andrew and Michael and I discussed it for a while and just decided to roll the dice and go for it, which was a really smart decision because Lukas delivered, and it gave our director a shorthand and a sense of comfort in taking on a camera crew entirely unknown to him.”

Ettlin traveled to Austin early in pre-production to interview potential crew, and in the process, learned a great deal about how the first movie was shot. He also relied on the experience and skill of his two seasoned camera operators, Michael Scott and Brown Cooper.

“I brought a lot of enthusiasm to the project, but as you’ve heard a million times before, movie making is a team effort, and I really depended on the entire crew,” says Ettlin.

Liebesman, Ettlin and Rubeo decided on a red, white and blue color theme. “We talked through a lot of conceptual ideas about the innocent, hard-working farm family, making little to nothing through some very lean years, and what came out of those discussions was the idea of using a desaturated American flag for our color pallet,” says production designer Rubeo. From there, we added some ochre and sepia tones used in the previous film in order to tie some elements of both movies together.”

Liebesman remembers looking through a book of photographs from the 1940s. “They were old faded photographs of what America wanted to be, and what this family was trying to be, but failed to manage. The fading color seems almost to represent the decay of the American dream, the family that’s gone off the rails.”

Liebesman also credits set decorator Randy Huke, who previously worked on the 2003 remake, for her attention to detail and her ability to keep the art department on track. “It was a great group effort, and a testament to Randy’s patience and professionalism to be able to work with all of us new guys,” Liebesman says.

“We took our lead from the 2003 movie,” Ettlin says. “I think it was so popular because it felt real to people. It was shot so that the audience felt like they were in the middle of the action, almost cinema verité. That’s why it’s such a cult movie. You never know where things are coming from and you never have a chance to relax. That’s something we wanted to continue in this installment; we never want the intensity to let up so the camera never settled, it just keeps moving. This idea evolved through the shoot.”

“As the story progresses and we move from romance and beauty lighting to the car crash that begins the horror, we changed the shutter angle from 180 to 90 degrees to make everything staccato,” he says. “So the action becomes more hectic and extreme, which informs the audience that they’re about to start a wild ride.”

Most films are not shot in chronological order. Between location availability, talent schedules, time and weather constraints, it is simply too difficult to plan production around the sequence of events as laid out in the script. Be that as it may, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Beginning was filmed in as close to chronological order as possible, which meant the company began working days and slowly moved into night shoots for the last several weeks of production.

“When you’re making a film like this, you want to ease your actors into it,” explains Andrew Form. “By the end of the movie, the characters have been through so much that they’re exhausted. You also need to let the emotion and terror build. It’s important not to throw someone into a death scene on day two, especially given the physically taxing nature of the film.”

“I heard Brad Fuller try and persuade some of the actors not to take the job,” Form recalls with a smile. “That’s how physically demanding the movie is. Brad would say, `Are you sure you want to do this? Because it’s going to be hot, it’s going to be cold, you’re going to run like crazy, you’re going to fall down. And we need you to do it a thousand times. So are you sure you want to do this?’ Commitment, that’s what we’re looking for.”

Jordana Brewster was amused by the warnings. “It shocked me how low their standards were in terms of what Brad and Andrew thought I could handle, as if I were this princess,” she says. “Andrew made fun of the way I ran because I was used to running on a treadmill which forces you to have good form. The first time I was running away from Leatherface, he told me that I looked like I was running in Chariots of Fire. He explained that he wanted me to run `messy,’ you know, with your arms up in the air,” she laughs.

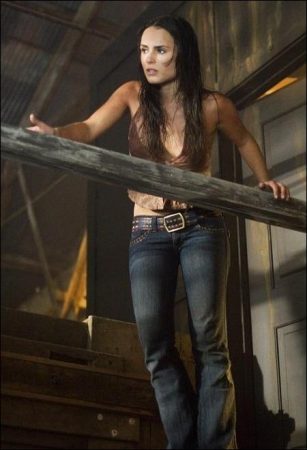

“But sometimes you do have to remind the crew that we’re not machines and we can’t fall down 10 more times after doing it all day, but I hope I’ve proven the princess idea wrong. Actually for me the hardest thing was shooting in 30-degree weather wearing jeans and a halter-top,” she confesses.

The film takes place in summer, but because many of the night scenes were filmed in November and December during a record-breaking cold front that hit Texas and much of the south, the film’s first assistant director, K.C. Hodenfield, asked the actors to suck on ice cubes before each take so that their breath would not be visible. An uncomfortable task, to say the least, especially because the actors were constantly running and breathing as though they were terrified.

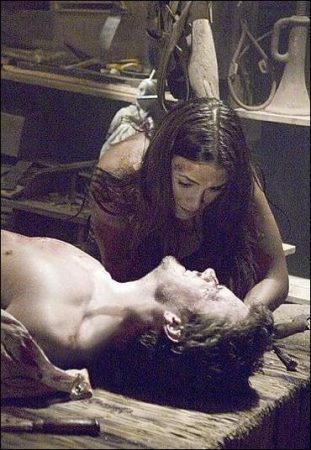

Although you’d never think lying down could be difficult, Matt Bomer spent several punishing days on a hard wooden table, remaining still for hours at a time. As Bryniarski does his Leatherface worst to Eric, Bomer is chained to a table in the Hewitt basement, with no shirt, covered in fake wet blood, even during a freak ice storm that sent temperatures dipping into the teens.

The filmmakers depended on celebrated stunt coordinator Kenny Bates and his second-in-command, coordinator Kurt Bryant, to create the most critical moments in the film, while keeping the cast and crew safe at all times. The two coordinators and Michael Bay have a long history together working on many movies, videos and commercials. When it comes to action, they speak the same language.

“Kenny can take the most complex stunt and break it down to make it understandable for everyone, including the novice,” says Brad Fuller. “He’s known for the quality of his work, and Kurt just continues that practice, plus he is meticulous about safety. On shows like this, it is inevitable that people get scratched and bruised, but we never worry about someone getting seriously injured, and that’s the comfort zone we have working with Kenny and Kurt.”

Bryant worked tirelessly with the cast: coordinating the car accident that begins the kids’ downfall; helping Andrew Bryniarski pull Diora Baird out of a moving vehicle; hanging Taylor Handley and Matt Bomer from beams in an empty garage on the Hewitt farm; staging a complicated fight sequence between Handley and R. Lee Ermey; and, of course, designing the menacing dance of the ever present chainsaw.

For Brewster, there was an additional challenge of working without a partner, acting directly to camera. “I’ve never done that before,” admits Brewster. “I’ve never had a director talk to me during a take. I’d be sneaking around, hiding, or looking around corners and Jonathan would say, `OK, now you see this, now you see that. Look left, move a little to your right.’ It’s incredibly technical, and as an actor, you’d think it would be boring, but it wasn’t.”

In discussing the physical aspects of filming a horror movie, it is impossible not to look at the concept of torture. Where do the filmmakers draw the line? Does a line even exist? It was a constant conversation on set between Form, Liebesman and Fuller.

“Jonathan and Brad never thought there was enough torture,” claims Form, before Fuller can cut him off.

“Torture is a really difficult thing to watch,” Fuller explains. “I’m not going to make any bones about it. I am squeamish. And when it’s on the monitor, there were times I had to walk away because it was so brutal. But that’s what this family is into, and as a viewer, it wouldn’t be effective if you didn’t care about the people being victimized.”

“Torture is a main component of the film,” he continues. “But you don’t want torture to be more important than the actual story, so if it takes you out of the moment, then it’s too much. But we can’t know that when we’re filming individual scenes, so we pushed it as far as we could.”

“And it’s not about the blood,” Fuller declares. “We’re not gratuitous because the horror and the terror come from the situations, not the amount of blood flying around.”

KNB Effects, Inc. was in charge of the special effects makeup, the prosthetics for Leatherface and all the blood work. With over 500 movies under their collective belts, Greg Nicotero, Jake Garber, Kevin Wasner and the other artisans at KNB were always prepared for anything thrown their way during production.

Jordana Brewster was especially stunned with the amount of blood work her scenes entailed. She jokingly says that she enjoyed the first three days of production the most when she and her cohorts were clean and dry.

“I was really affected by all the blood at first,” she says. “Emotionally, I was taken aback, but after a while, the blood lost its shock value and just became annoying because it was wet and cold, and really sticky and sweet. You’re basically fly paper attracting insects. It’s just gross, especially when you have to walk around in it all day and night.”

Most of the cast spent their fair share of time dripping in blood, some of them having been fitted with molds for latex appliances and prosthetics at KNB’s shop in Los Angeles prior to start of principal photography in Texas on October 10th, 2005.

KNB not only supplied gallons upon gallons of fake blood and prosthetics, they also designed two new, early versions of the famous Leatherface mask.

“One of the big storylines in the movie is the evolution of the mask,” says Andrew Form. “During the first half of the movie, Thomas Hewitt wears what he had probably made as a child to cover his scarred and blistered face and protect himself from ridicule. We made a choice to go with what we called a `half-mask’ for this.”

“KNB took a long time designing that mask,” affirms Michael Bay. “In my mind, I always saw it as a leather strap that he had around his nose to cover a skin disease. From there I imagined him using animal skins which evolve into human skin.”

“About three-quarters of the way through the movie, Thomas puts on a full mask that he’s made after a kill,” Andrew Form continues. “He’s obviously less skilled than he is in the 2003 movie because this is the first time he’s peeled off the skin of someone’s face.”

In keeping with the idea that Leatherface has three years less experience in the art of murder, the filmmakers were vigilant about keeping actor Andrew Bryniarski in check, especially when it came to his skill at wielding the chainsaw.

“These are his first kills,” director Jonathan Liebesman would remind Bryniarski. “This is not an art form yet. You are clumsy and stumbling through it. Thomas is not aggressive and ready to kill at the drop of a hat. It takes him a little while to get wound up and become Leatherface.”

In comparing The Beginning to the 2003 hit, Liebesman says he was “inspired by director Marcus Nispel’s style, but didn’t want to duplicate it. We went for a bit of a documentary feel,” he says, “less stylized than the first movie. Certain shots were iconic and we paid homage to those images of Leatherface.”

“Jonathan made his own movie,” says Michael Bay. “He really did. I think The Beginning has more personality than our remake of the original, because it was just that, a remake. Jonathan focused on different things and made his own unique horror film.”

Although Bay only visited the set twice during production, he watched dailies and spoke with Liebesman on a daily basis. “It’s better for me not to be on set,” he says. “But I remember what it was like to be a new director and get those calls from the producer. I would dread them, but they were useful because the advice is helpful and you become better at what you do. It’s difficult to use the palette of one movie while trying to step away from it to make your own mark, but Jonathan has done just that with The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Beginning. It’s a new look at a favorite, time-honored masterpiece of horror.”

The filmmakers anticipate that audiences will be excited and terrified to discover how the Hewitts became a clan of crazed murderers, and hope that lovers of their 2003 film and the 1974 original will embrace this new story and enjoy a new chapter of brutality and terror so emblematic of the genre.

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Beginning (2006)

Directed by: Jonathan Liebesman

Starring: Jordana Brewster, Andrew Bryniarski, R. Lee Ermey, Taylor Handley, Matthew Bomer, Diora Baird, Heather Kafka, Marietta Marich, Terrence Evans

Screenplay by: David J. Schow

Production Design by: Marco Rubeo

Cinematography by; Lukas Ettlin

Film Editing by: Jonathan Chibnall, Jim May, Joel Negron

Costume Design by: Mari-An Ceo

Set Decoration by: Randy Huke

Art Direction by: John Frick

Music by: Steve Jablonsky

MPAA Rating: R for strong horror violence/gore, language, sexual content.

Distributed by: New Line Cinema

Release Date: October 4, 2006

Views: 334