Tagline: Innocents lost… sometimes forever.

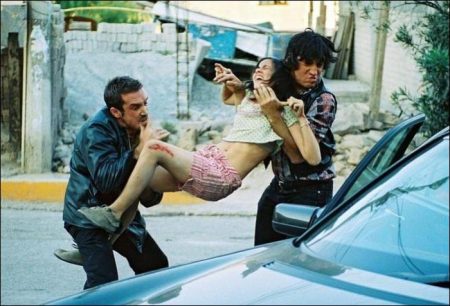

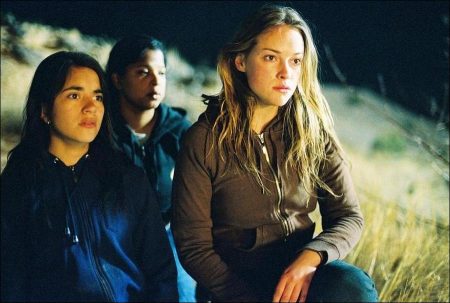

Trade movie storyline. Adriana (Paulina Gaitan) is a 13-year-old girl from Mexico City whose kidnapping by sex traffickers sets in motion a desperate mission by her 17-year-old brother, Jorge (Cesar Ramos), to save her. Trapped and terrified by an underground network of international thugs who earn millions exploiting their human cargo, Adriana’s only friend and protector throughout her ordeal is Veronica (Alicja Bachleda), a young Polish woman tricked into the trade by the same criminal gang.

As Jorge dodges immigration officers and incredible obstacles to track the girls’ abductors, he meets Ray (Kevin Kline), a Texas cop whose own family loss to sex trafficking leads him to become an ally in the boy’s quest. Fighting with courage and hard-tested faith, the characters of Trade negotiate their way through the unspeakable terrain of the sex trade “tunnels” between Mexico and the United States.

From the barrios of Mexico City and the treacherous Rio Grande border, to a secret internet sex slave auction and the final climactic confrontation at a stash house in suburban New Jersey, Ray and Jorge forge a close bond as they give desperate chase to Adriana’s kidnappers before she is sold and disappears forever into this brutal global underworld, a place from which few victims ever return.

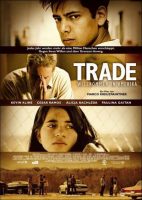

Trade is a 2007 American drama film directed by Marco Kreuzpaintner and starring Kevin Kline. It was produced by Roland Emmerich and Rosilyn Heller. The film premiered January 23, 2007 at the 2007 Sundance Film Festival and opened in limited release on September 28, 2007. It is based on Peter Landesman’s article “The Girls Next Door” about sex slaves, which was featured as the cover story in the January 24, 2004 issue of The New York Times Magazine.

About the Production

The story of Trade begins in 2003, when reporter and writer Peter Landesman spent five months in the barrios of Mexico City reporting a ground-breaking cover story on sex slavery for the New York Times Magazine. Landesman had gained a reputation for tackling provocative stories; he had covered the wars in Kosovo and Afghanistan, and reported on the dealings of global arms traffickers.

But his report from Mexico, Sex Slaves on Main Street, was perhaps the most controversial of all, revealing for the first time the hidden, horrifying crime network of child sex trafficking operating in the U.S., Mexico and Europe. On the Times’ website the article became the most requested story of the year, and was awarded “Best Foreign Reporting on Human Rights Issues” by the Overseas Press Club (the magazine world’s Pulitzer).

“It all began when my wife — Kimberlee Acquaro, the photojournalist on the story — saw a local news story on TV about Mexican girls who had been found prostituting themselves in the reeds outside of San Diego,” he recalls. “When I went down to investigate, immediately it seemed there was something missing in the news story – something hidden, wrong, unsaid.”

Within a week of reporting, the writer found himself inside an “unspeakable” network of sex traffickers who were kidnapping girls, young women and sometimes adolescent boys and smuggling them across the U.S.-Mexican border. From there, they ferreted their sex slaves into secret stash houses littered across the cities and bedroom communities of America. Usually they would drug their victims into submission and hold them hostage for months or years while selling their bodies for outrageous profits. Most were unable to escape these trafficking “tunnels,” and many were never heard from again.

Producer Rosilyn Heller had already heard of Landesman through his prior articles and screenplay commissions when her friend and producing partner, Gloria Steinem, brought him to Heller’s home for a dinner party. After learning he was writing a story about sex trafficking – an issue close to her heart as a long-time advocate for women’s rights – she sensed the groundwork for a compelling film with deeply personal and relevant storylines.

“People are always quick to point their fingers and say this is a problem that exists overseas, in Southeast Asia, Eastern Europe and Africa,” Heller notes. “But that’s not true. It’s also right here in our own backyard.”

Heller then called her close friend and producing partner, the director Roland Emmerich. Would he consider taking on the project? “Roland of course was known for these huge successful studio movies like Independence Day, The Patriot and The Day After Tomorrow,” Heller says. “But I knew he was also deeply committed to doing smaller, more provocative political and personal pieces. I knew he had a tremendous interest in Mexico’s culture and people. I was thrilled that he unequivocally said ‘yes.’”

With Emmerich’s purchase of the rights to Landesman’s story, the director of some of Hollywood’s biggest blockbusters became the de facto godfather of one the most intimate and powerfully-themed projects to hit the independent film community. “This was such an important story for me that I was determined to see this ‘little’ project born,” notes Emmerich.

The Writing of Trade

The next step was to develop a script treatment based on Landesman’s article. Under Emmerich’s and Heller’s supervision, Landesman wrote a treatment about a Texas cop who had fathered a daughter lost to the world of sex trafficking, and a young Mexican street kid whose life is forever changed when he runs away to America to rescue his kidnapped sister from one of the underground trafficking networks.

“I wanted to make this a story about a kid who could have been one of these young traffickers,” Emmerich says. “He was being practically trained for it, yet in an instant his whole life – and his whole mission in life – changes 180 degrees, and that’s what we follow. We didn’t want to make a political or social docudrama about sex trafficking. And we didn’t want to romanticize the story in any way, because it’s so devastating. We simply wanted to make a personal story from the victims’ point of view, because that’s a story an audience can care deeply about.”

With Landesman himself already committed to screenplay projects for Oliver Stone and Michael Mann, Emmerich and Heller approached Puerto Rican-born writer Jose Rivera, who had recently written the acclaimed feature Motorcycle Diaries starring Gael Garcia Bernal. Rivera immediately responded to the subject matter. “We were so lucky because he hadn’t been nominated for the Academy Award yet for Diaries, so it was easier to get him,” says Heller. “As a Latino he had an innate feeling for the world inhabited by these characters.”

In the summer of 2005, Heller and Rivera trekked down to Mexico City on a research trip to visit many of the neighborhoods later portrayed in the film. Among them was the barrio of La Merced, where they witnessed an extraordinary daily ritual chronicled in Landesman’s article. Called “la parabola,” the haunting scene featured a line of prostitutes, aged from about 14 to 60, circling around in an alley, completely surrounded by a ring of men wordlessly picking their favorites. The scene was “especially disturbing,” Heller recalls, because it took place in broad daylight during the men’s lunch break: “For many women this was clearly their livelihood. But you sensed there were girls among them who were not there voluntarily.”

The trip to Mexico had a profound effect on Rivera in particular. “The original material was heartbreaking – you have to be made of stone not to respond to what the article was about,” the screenwriter remarks. “And that was magnified by meeting some of the girls at the women’s shelters we visited in Mexico. There were runaways and some of these kids had been sex slaves, and what was most inspiring was just how trusting they were in sharing their stories.”

One story in particular impressed the screenwriter, that of a 12-year-old girl who, at the age of nine, had been sold into the sex trade by her uncle. “She had been beaten many times, she had been forced to do horrible things like assist in the abortion of a friend’s fetus and then bury it in the middle of Mexico City,” Rivera recalls. “Yet this girl refused to feel sorry for herself or indulge in self pity, and that impressed me enormously. You could see her tenacity and her survivor strength through her tears. This amazing girl became my model for the character of Adriana in the film.”

A little over three weeks after he returned to Los Angeles, Rivera had a first draft of the screenplay, then called The Girls Next Door, ready to show Emmerich and Heller. “I was able to write the draft fairly quickly, thanks in part to the detailed outline, which I also redrafted,” says Rivera. The hardest scene to write was the rape scene of Veronica in the stash house. “In the story the whole act is being videotaped by one of the gang members, and that videotape ends up on a porn website as entertainment. On a moral level, that was the toughest part for me to deal with.”

Emmerich found Rivera’s first draft of the script so compelling that he committed to direct the project the following March. But then came the inevitable and lengthy complications of cobbling together the roughly $12 million budget for the movie, and the movie’s start date kept getting pushed back. Though it would have been easier to find funding through a studio, both Heller and Emmerich were adamant that the movie be made independently in order to preserve as much control over it as possible.

Other major commitments began beckoning the director, too. One project, in preproduction at Warner Bros., was the action-adventure epic 10,000 B.C. It was looking increasingly uncertain whether production schedules would allow him to direct all the projects on his plate.

Peter Landesman Talks About the Sex Slave Trade

Peter Landesman’s groundbreaking article in The New York Times Magazine, “Sex Slaves on Main Street,” inspired a national conversation on a topic left largely unspoken in the American media. Since the story’s publication in January 2004, news articles, documentaries and websites worldwide have finally begun to shed light on the human and social costs of this multibillion- dollar, multinational slave trade. And the federal government has initiated legislation and law enforcement programs to help stop the trade.

Now, with the release of Trade from Lionsgate Films, the shocking underworld first exposed by Landesman finds its most compelling expression in the deeply human story of a boy and a policeman’s unlikely journey to reunite their families that have disappeared into the “tunnels” of international sex traffickers.

With tens of thousands of women and children kidnapped each year by these prostitution and drug rings, Landesman contends that Americans can no longer remain bystanders to the global growth of sex trafficking, because these crimes are happening in their own backyard.

“People who live in these towns I wrote about responded to the story with disbelief, rejection, horror at what was taking place next door,” he remarks from his home in Los Angeles. “It’s a little like battered wife syndrome; they know it’s happening to them, but they don’t want to know. I don’t think it’s a matter of not accepting it. I just think people had no idea.”

Landesman’s five-month investigation of the “tunnels” of sex slavery across the U.S.- Mexican border lead him through a labyrinth of organized crime whose scope was as daunting as its motives.

“It’s an extraordinary economy, primarily because the capital it takes to start up a business is zero,” he reports. “You kidnap a girl, you pay her nothing. You don’t pay anyone else for that human being. So you can make hundreds of thousands of dollars a year off a single girl.”

Of the estimated 600,000 to 800,000 men, women, and children trafficked across international borders each year, approximately 80% are women and girls, and about 50% are minors, according to recent State Department reports. Landesman estimates that about 100,000 or more men, women and minors are trafficked into the U.S. every year. Still, he cautions that any numbers are merely a best guess when it comes to the trafficking of drugs, weapons, or humans: “After all, traffickers don’t file with the IRS, and no one’s at the border with a clicker counting who’s coming across.”

In his own reporting for The New York Times, Landesman discovered that many of these girls, some as young as 11 or 12, are forced to have sex with up to 30 men a day. The going rate starts at around $20, with clients paying as high as $100 if the girl is a virgin. “Just do the math,” says Landesman. “With each trafficker controlling five, 10 or 20 girls for 365 days a year, it’s an enormous business.”

Within the U.S., the sex slave market is stratified between low-end prostitutes brought in by Mexican field hands, and girls targeted for the high-end prostitution market who are kidnapped from countries like Ukraine, Moldova and Poland, the home country of Veronica in Trade. Many of these victims are enticed into the network by “travel agents” who lure them with exotic tales of becoming movie stars and supermodels, of living the good life under the waving palms and beckoning sun of Hollywood.

Their dreams inevitably shattered, these girls can be seen entertaining clients in almost any local strip joint across America. Many are found “offering” their high-end services on the web, while still others are sold outright as chattel for tens of thousands of dollars each, via secret, password-protected Internet auctions. If any of the girls try to escape from these tunnels of sex slavery, they and their families back home can be physically threatened, harmed and even killed.

“The horrifying nature of sex slavery is the invisibility of it,” Landesman continues. “The reality is that if you drive down Hollywood Blvd. in Los Angeles or Roosevelt Ave. in Queens (New York) or Michigan Ave. in Detroit, you’ll see girls on the streets in hot pants, some of them strung out on drugs, some looking perfectly healthy. And you know they’re hookers and whores. But what you don’t know – what you can’t see and what is so deeply disturbing – is that many of them are not those girls but these girls, girls who are forced into slavery under the threat of death.”

Landesman recounts one particular visit he paid to a neighborhood nestled among the maple trees and flapping flags of Plainfield, New Jersey – the setting of the final, dramatic rendezvous in Trade. Next door to a convenience store “where you and I would go to shop,” the reporter found a stash house where 13 underage Mexican girls were trapped, raped and starved for months and years at a time.

“The scene looked like a slave ship,” he recalls. “There was almost nothing in it except mattresses on the floor. There were tranquilizers and narcotics and chemicals that if you ingest will induce spontaneous abortions. The girls were chained. If you could have imagined your worst nightmare of what would happen to your daughter or sister or mother, this was it. And this was in Plainfield, New Jersey.”

Perhaps the most devastating story Landesman heard in all of his weeks of research was that of young American girl – a girl he referred to as “a cutter” – who had been held captive in a basement crammed with children in southern California. She had been trafficked back and forth across the Mexico-US. border from the age of four until she escaped, at age 17.

Her story was “almost impossible to listen to” over the course of three days, Landesman reports. It was so extraordinarily hard for her to tell that every couple of hours “she would stand up and leave the room to go to the bathroom, where she would cut herself with a knife just to relieve the tension of talking about it.”

The reason her story is unique is because girls like this are usually dead by the time Landesman gets to them. “Of all the things I’ve seen and covered, hers was the most difficult to hear, and yet in some ways also the most heartwarming because she’s alive and still kicking.”

* * *

Landesman acknowledges that all the controversy and awareness generated by his exposé of the sex slave underworld may not, by itself, be enough to arouse governments or communities to fight the good fight to change that world.

“The complicity of these governments on the local level – and especially Mexico on a national level – is undeniable and, in many ways, unstoppable,” he observes. “To most of us, sex trafficking is the most abhorrent phenomenon. But when it comes to the agendas of national governments of international institutions like the UN, sex trafficking doesn’t even make it onto the top twelve. After all, the last thing the U.S. wants is to make an enemy of the Fox administration in Mexico, so they’re not going to press very hard on this issue. They’ll make public hay with a press item about this piece of legislation or that border raid, but that’s about it.”

To follow these trafficking tunnels deep into their political and social bulwarks leads inevitably to a single source: poverty. In the countries of origin of these kidnapped children — Moldava, Ukraine, Russia, Nigeria, Mexico and Thailand, to name but a few – the policemen are among the poorest paid of any profession. How, Landesman asks, are these cops to put food on the table to feed their kids? Partly by dealing with traffickers.

“The traffickers themselves don’t want to kill people, but they do want to identify themselves with something they can belong to – a network, different kind of family, barbaric as that is.”

Landesman says that in America, the biggest problem in stopping trafficking may be the police themselves, but not because of corruption. “When an ordinary cop sees these girls on the street, they don’t know what they’re looking at. Most of the girls themselves don’t know how to speak English; they can’t ask for help, and since in their own countries the cops are the bad guys, they don’t go to the police. They turn around and run the other way.”

In the end, Landesman believes it is conundrums like these which make it virtually impossible to stop, or even significantly stem, the tide of sex trafficking. “The only way to stop this on a global level is to stop local corruption and reel in the local police,” he ventures. “And how do you do that? You would have to stop the whole phenomenon of poverty. Call it cynicism, pessimism or just hardened reality, but that we will probably never do.”

Trade (2007)

Directed by: Marco Kreuzpaintner

Starring: Kevin Kline, Cesar Ramos, Alicja Bachleda, Paulina Gaitan, Marco Perez, Linda Emond, Zack Ward, Kate Del Castillo, Guillermo Iván, Christian Vazquez

Screenplay by: Jose Rivera

Production Design by: Bernt Amadeus Capra

Cinematography by: Daniel Gottschalk

Film Editing by: Hansjörg Weißbrich

Costume Design by: Carol Oditz

Music by: Leonardo Heiblum, Jacobo Lieberman

MPAA Rating: R for disturbing sexual material involving minors, violence including a rape, language and some drug content.

Distributed by: Sony ScreenGems

Release Date: September 28, 2007

Views: 139