A Conversation With Director James Gray

The film Two Lovers was directed by James Gray. James Gray (born April 14, 1969) is an American film director and screenwriter. Since his feature debut Little Odessa in 1994, he has made seven other features including We Own the Night (2007), Two Lovers (2008), The Immigrant (2013), The Lost City of Z (2016), Ad Astra (2019) , and Armageddon Time (2022). Five of his films have competed for the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival.

Below you can read an in-depth interview with James Gray about “Two Lovers.”

How does Two Lovers compare to your first three films? What prompted you to shift gears from the crime thriller genre to a romantic drama?

As a filmmaker, you’re always trying to refine and make clearer your ideas. So I guess what I was looking for was a way to make a film that appealed entirely to emotions and not at all to intellectual pursuits or genre convention. Making a romantic drama allowed me to focus on the authenticity of emotion, without having to pay attention to the machinery that goes along with crime dramas.

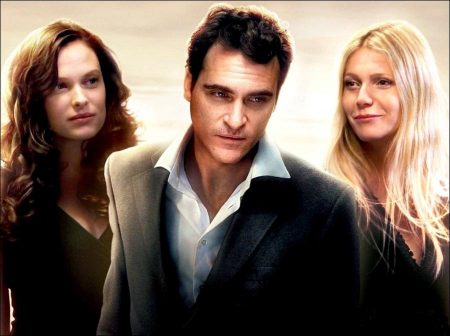

Two Lovers is your third film working with Joaquin Phoenix, and you have worked with him more than any other actor. Can you talk about what attracts you to working with him?

Joaquin and I have very similar ways of looking at the world. We both have a real interest in trying to examine human behavior in a way that.s honest and truthful. Joaquin has a real ability to relate to an audience a complexity and internalized conflict in ways that are not necessarily verbalized. To look at him, you know what he.s thinking. That.s a very important quality for an actor, and as a director, when you find that you have to make sure you hold on to it. Because that.s really the essence of drama—both an external and internal conflict for the main character—that.s the way that complexity gets born. And beyond that, he and I are quite friendly and get along very well. We share many of the same tastes, and I feel very lucky to work with someone like that.

Phoenix gives a brave and vulnerable performance in this film, as does Gwyneth Paltrow. What is your method working with actors in order to elicit this kind of emotional intensity?

The key is really to explain right upfront at the beginning of the process, what your ambitions and goals are for the piece. And I think what I stressed to both Joaquin and Gwyneth on a virtually daily basis, was to not put a wall between themselves and their characters. It is so important to me that they never put themselves above their character, never look down on their character, never think that they.re smarter than their character. I want there to be no separation between my actors and the person they.re playing. And that to me is where one can achieve a certain emotional honesty in a film.

How did you go about casting the three leads?

When you.re casting, you.re looking for people who understand what it is that you.re trying to say. You look for people who are sympathetic and empathetic with your cause.

In Joaquin.s case, of course, I’d worked with him before, and I knew that this pursuit of a certain emotional honesty was what he was interested in. I.d known Gwyneth socially for many years, and we.d talked about working together for some time. So I pretty much wrote the movie with the two of them in mind, feeling like this was a great opportunity to make a picture where there would be no artifice to the emotion. In the case of Vinessa Shaw, I wanted someone who was appealing because to cast someone who was homely would be both a cliché and to miss the point of the story itself, which is that obsession makes one blind to qualities of the other person. And again—that doesn.t mean there.s no artifice to the movie, because movies are always a heightened reality. But it means that the actors are not distancing themselves from the people they.re playing. I think that.s a very important idea, especially today, because that is very rarely done in movies anymore.

Leonard Kraditor is a grown man in his 30s living at home with his parents; Michelle Rausch is another adult wrapped up in an emotionally immature relationship with a married man. Both of these characters seem to be living in a state of arrested development. Can you comment on this?

I think that one the essential struggles that we face in life is reconciling our hopes and dreams that seem so very clear and reachable, with the countless difficulties and injuries to our psyche that keep them from becoming reality. I think it.s very common that people live in states of arrested development, because one of the rarest qualities in the world is emotional intelligence. I know that there are a significant percentage of people who are in their 30s and live with their parents.

The state of being in love is preposterous—we never leave adolescence when we are in love. We say and do such absurd and immature things, so to me, this state of arrested development was important to establish in order to justify the absurdity of being in love. These characters needed to be the ages they are—if they were 20 years old, then the essence of the story would be homogenized pap, because you wouldn.t get a sense that their struggle was one of life and death. Once you get to be a certain age, these puerile conflicts become much more important because essentially it means that your neuroses are becoming encrusted and quite severe.

You deal with very classical themes in your films, especially that of fate and predestination, and notably the seeming impossibility of class mobility. In Two Lovers, Leonard seems tied to a life in the family business and destined to marry the daughter of his father’s business partner. Can you talk about your feelings about fate vs. free will and what this means for the characters in your films?

I would prefer of course for the audience to draw their own conclusions when they see the work, but my own view is that we overstate the importance of free will. There is, of course an element of free will in all behavior. But at the same time, we are all products of our cultural and ideological boxes, and so our ability to make what is deemed the “correct” decision by society is usually totally informed, if not forced upon us by our own position in the world. Our ability to choose is inextricable from our culture, ideology, social class, economics, history—all the factors that go into making us who we are.

The idea that you can pull yourself up by your bootstraps is a very entertaining one, but I think it would be grossly negligent not to question this. Obviously some people really can rise above their original circumstances—this country is essentially founded on that idea. But I think many more people are totally unable to do that. This is an unpleasant and unpopular notion because it means that we don.t have as much control over ourselves as we.d like to believe we have, but to me it seems like a more honest way of dealing with the way the world works. And I think it.s important to question what differentiates people who are able to rise above their circumstances from those who cannot.

Some of your previous films are notable for their ambiguous endings. How does the ending of TWO LOVERS compare?

I think it.s ambiguous as well. Outside of musicals and comedies, happy, upbeat endings can feel phony. Unhappy endings can feel indulgent and over-the-top. My ideal is an ending that hews closer to real life experience, which has both the bitter and the sweet. I think an ending that has both of those components comes closer to capturing the richness and complexity of life as we experience it. I.m not saying we pulled it off with Two Lovers—that.s for the viewer to decide, but that.s definitely what we were going for. I hope you can perceive multiple meanings from the ending.

Two Lovers has a tremendous sense of place and atmosphere. As a filmmaker, how do you go about creating such vivid moods and powerful imagery?

Several things go into what you.re talking about. If you know the neighborhood and the surroundings, then a certain verisimilitude accompanies the images and gets an emotional response from the audience because it feels real and honest. Another important element for establishing tone and mood has to do with sound and silence—with music or lack thereof. Also the duration of a shot, what the focus is, and what.s in the background. All of these decisions go into defining the tone and atmosphere of a film. So what I try to do is focus on my sensory memory of the places I.ve been, lived, or like to depict, and impart all of these principles to that. And hope that establishes a firm sense of environment for the characters.

Two Lovers is loosely based on a story by Dostoyevsky which was also adapted by Luchino Visconti into a film called “White Nights.” Can you talk about how you drew inspiration from the Dostoyevsky, and how your film is different from or inspired by Visconti’s?

Well, I had pulled “White Nights” off the shelf one night looking for something to read, and what stuck me about it was its psychological complexity, its total commitment to the protagonist, and its direct assault on the subject of love.

What do you mean by a “direct assault on the subject of love”?

Well, in a sense, love is preposterous and a lie. That doesn.t mean it.s a lie to you. In other words, you may think you.re in love with another person, but really, what you love about that person tends to be what you project upon that person, and what you love in them that you feel you lack yourself. So the love is real to you, but it.s not necessarily objectively real—it.s subjectively real. The character in “White Nights” thinks he’s in love, but really, he knows nothing about the woman he.s in love with. But just because we think his position is absurd, that doesn.t mean it.s absurd for him, for him it.s real, because he feels it.

So I stole some elements of the plot from “White Nights.” But you couldn.t really do a Dostoyevsky story in present day, because many of his protagonists would be recognized rather quickly as having any number of psychological problems, which in present day would be mitigated, or result in the character being put in an institution. So I stole elements that seemed to work in a modern framework, then tried to update it as best as I could.

Visconti’s White Nights is a marvelous movie, but it.s very surreal—from the Dostoyevsky story he achieves a beauty through heightened reality. It was all shot on a soundstage and it.s a very lovely film, but obviously a formally adventurous one, and I was not anxious to repeat that here. So the two films feel very different, I think.

What other films inspired you while you were making Two Lovers?

I was looking at Vertigo, because that.s a wonderful film about love and obsession and fetish. And I was inspired here by a lot of Fellini, not the least of which was Nights of Cabiria and La Strada—in fact I stole the ending of the beach from that movie. And to speak more generally, I was certainly influenced by the kind of expressive, unapologetically emotional elements of European cinema of the „50s and „60s, and a lot of the American pictures from the early „70s, because those movies seem to be very committed to storytelling, but also committed to emotional honesty, without what you could call the hip or ironic tone that accompanies much of independent cinema today.

Two Lovers (2009)

Directed by: James Gray

Starring: Joaquin Phoenix, Gwyneth Paltrow, Vinessa Shaw, Isabella Rossellini, Elias Koteas, Moni Moshonov, Elliot Villar, Christian Albrizo, Donald John Hewitt, Samantha Ivers, Anne Joyce

Screenplay by: James Gray, Ric Menello

Production Design by: Happy Massee

Cinematography by: Joaquín Baca-Asay

Film Editing by: John Axelrad

Costume Design by: Michael Clancy

Set Decoration by: Carol Silverman

Art Direction by: Marc Benacerraf, Pete Zumba

MPAA Rating: R for language, some sexuality and brief drug use.

Distributed by: Magnolia Pictures

Release Date: February 13, 2009

Views: 151