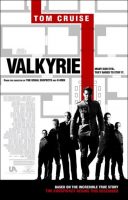

Tagline: Many saw evil. They dared to stop it.

Valkyrie movie storyline. In a country in the grips of evil, in a police state where every move is being watched, in a world where justice and honor have been subverted, a group of men hidden inside the highest reaches of power decide to take action. Tom Cruise stars in the suspense film, “Valkyrie,” based on the true story of Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg and the daring and ingenious plot to eliminate one of the most evil tyrants the world.

A proud military man, Stauffenberg is a loyal officer who serves his country all the while hoping that someone will find a way to stop Hitler before Europe and Germany are destroyed. Realizing that time is running out, he decides that he must take action himself and joins the German resistance. Armed with a cunning strategy to use Hitler’s own emergency plan – known as Operation Valkyrie – these men plot to assassinate the dictator and overthrow his Nazi government from the inside. With everything in place, with the future of the world, the fate of millions and the lives of his wife and children hanging in the balance, von Stauffenberg is thrust from being one of many who oppose Hitler to the one who must kill Hitler himself.

Valkyrie is a 2008 American-German historical thriller film set in Nazi Germany during World War II. The film depicts the 20 July plot in 1944 by German army officers to assassinate Adolf Hitler and to use the Operation Valkyrie national emergency plan to take control of the country. Valkyrie was directed by Bryan Singer for the American studio United Artists, and the film stars Tom Cruise as Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg, one of the key plotters. The cast included Kenneth Branagh, Bill Nighy, Eddie Izzard, Terence Stamp and Tom Wilkinson.

About the Production

Based on a stunning true story, Tom Cruise stars as Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg in the suspense film VALKYRIE, a chronicle of the daring and ingenious plot to eliminate one of the most evil tyrants the world has ever known.

A proud military man, Colonel Stauffenberg is a loyal officer who loves his country but has been forced to watch with horror as the rise of Hitler has led to the events of World War II. He has continued his military service, all the while hoping someone will find a way to stop Hitler before Europe and Germany are destroyed. Realizing time is running out, Stauffenberg decides he must take action himself, and in 1942, on his own initiative, attempts to persuade senior commanders in the East to confront and overthrow Hitler.

Then in 1943, while recovering from injuries suffered in combat, Stauffenberg joins forces with the German Resistance, a long-existing civilian anti-Hitler conspiracy comprised of men hidden inside the highest reaches of power. Armed with a cunning strategy to use Hitler’s own emergency plan to stabilize the government in the event of his demise – Operation Valkyrie – and turn that plan on its head to remove those in power and cripple Hitler’s regime, these men plot to assassinate the dictator and overthrow his Nazi government.

With everything in place, and with the future of the world, the fate of millions, and the lives of his wife and children hanging in the balance, Stauffenberg is thrust from being one of many who oppose Hitler to being the one who must kill Hitler himself.

Director Bryan Singer (The Usual Suspects, X-Men, Superman Returns) re-teams with Academy Award-winning The Usual Suspects screenwriter Christopher McQuarrie to bring to life the story of the men who led the operation to assassinate Hiltler. In addition to Cruise, the film’s acclaimed cast includes Kenneth Branagh, Bill Nighy, Tom Wilkinson, Carice van Houten, Thomas Kretschmann, Eddie Izzard, Christian Berkel and Terence Stamp.

Valkyrie is produced by Bryan Singer, Christopher McQuarrie and Gilbert Adler. McQuarrie co-wrote the original screenplay with Nathan Alexander, who also serves as co-producer. The executive producers are Chris Lee, Ken Kamins, Daniel M. Snyder, Dwight C. Schar, and Mark Shapiro.

The film was shot in Germany at various locations where many of the actual events occurred, including the historic Bendlerblock. Recreating the atmosphere of urgency and paranoia inside the German Resistance is a team that includes Singer’s frequent collaborators Newton Thomas Sigel (Superman Returns, X2, X-Men) as director of photography and editor/composer John Ottman (Superman Returns, X2) as well as production designers Lilly Kilvert (two-time Oscar-nominee for The Last Samurai and Legends of the Fall) and Patrick Lumb (The Omen, Flight of the Phoenix) and costume designer Joanna Johnston (Munich, Saving Private Ryan).

The Story Begins

How a trip to Berlin set Bryan Singer, Christopher McQuarrie and Nathan Alexander on a quest to bring the German Resistance out of the shadows…

Bryan Singer began his filmmaking career with the highly acclaimed suspense thriller The Usual Suspects and went on to bring the comic book worlds of the X-Men and Superman to the screen with a dynamic originality. His direction is known for its edge-of-your-seat tension and gripping storytelling. But with Valkyrie, Singer brings those cinematic skills to a completely different kind of story – a true tale of extreme daring from inside the Nazi regime.

Although the events and heroes depicted in Valkyrie are real, they share much in common with the kinds of stories and characters that have always drawn Singer’s attention. Notes Chris Lee, an executive producer on the film and a long-time collaborator with Singer: “What always sets Bryan’s movies apart are the complexity of their characters, the emotions, and the absence of complete black and white, all married with a sense of pacing and action. Bryan’s ability to balance lots of intriguing characters started with The Usual Suspects and continued with the X-Men movies. Now it contributes something very powerful to the mosaic of remarkable individuals who make up Valkyrie.”

The story of Valkyrie was brought to Singer’s attention by screenwriter Christopher McQuarrie, a previous collaborator who won the Academy Award® for his intricately constructed screenplay for The Usual Suspects. In the winter of 2002, McQuarrie was in Berlin doing research for another project when, during a tour of the city, he came across Stauffenbergstrasse, the street named after German Resistance fighter Claus von Stauffenberg. There he found the Bendlerblock, the site of a monument to the German Resistance that McQuarrie found profoundly moving. “Berlin is a city of monuments,” McQuarrie’s guide told him, “but this is the only monument to any German who served in World War II.”

“Of course, I wanted to know more,” says McQuarrie. “Here was a very complex, remarkable story that most people outside of Germany had never heard before. It was a story that revealed not all Germans supported Hitler, that there were all kinds of resistors, including those in the military, and some who were willing to stand up and say no. The more I learned, the more I knew it would make a fantastic movie.”

And so it began. Continuing his research, McQuarrie was drawn in by Stauffenberg and his key role in planning the July 20, 1944, assassination plot against Hitler – including his ultimately carrying the bomb intended to change the world. McQuarrie became increasingly intrigued as to why some men are driven to acts of such extreme daring and profound conscience when their backs are against the wall. He began to see the story not just as a tale of mounting suspense, but one about the wages of courage and the way courage operates under extreme fire.

“A theme I am always attracted to is that of someone who is forced to step outside their reality and, by doing so, becoming a far bigger person,” McQuarrie says. “Stauffenberg and his co-conspirators were all men who had wives and children and established reputations. They knew going in they had little chance of success, and they understood if they failed it would mean certain destruction. That’s what we wanted to honor with this story.”

McQuarrie tapped writing partner Nathan Alexander to begin the intensive task of researching Stauffenberg’s complicated life and, most important, the precise machinations of the plot to assassinate Hitler and replace his authoritarian government with a shrewdly planned coup. As Alexander began poring through books, articles, court transcripts, and archival footage, he became increasingly excited about the potential to tell the story in a fresh and compelling way. “Stauffenberg is a fascinating character from the outset, this charismatic German officer with one eye and one hand,” says Alexander. “The more I learned about him, the more fascinated I became by who he was and how he ultimately came to do what he did.”

Initially, McQuarrie and Alexander allowed the research to drive the narrative of Valkyrie. “We didn’t set out with an agenda,” says McQuarrie. “We literally started by following the facts. We increasingly understood this was a controversial story, in that there remain many different opinions about whom each of these men were – from Stauffenberg to Beck to Olbricht – and what they each wanted. So the approach was to tell the story as truthfully as possible in two hours while conveying the pressure and suspense to a contemporary audience. In the midst of telling a gripping story, we wanted to really get the spirit that drove these men.”

As they wrote, the duo developed a unique process: Alexander would write an extremely detailed draft focusing strictly on the historical timeline, then McQuarrie would in turn write a draft zeroing in on maximizing the dramatic effect. “We’d go back and forth between these two poles until the pendulum rested in balance between the two,” says McQuarrie.

Ultimately, they found that the drama and tension of the story were inherent in the truth of what happened during this mission. The only significant changes McQuarrie and Alexander made to the facts of the story were compressing the timeline to fit a sleek, two-hour screenplay structure and compressing the number of characters involved; although some 200 people were hanged for their involvement and around 700 were arrested in direct connection with the July 20th Plot, a tightly-woven film narrative could only follow a handful of key players.

McQuarrie and Alexander did face a unique challenge in sustaining the story’s suspense for modern audiences – after all, Hitler’s ultimate fate is well known. They discovered, however, that the bombing was only half the story. The aftermath and the execution of Operation Valkyrie was filled with so many surprises – from fatal hesitation to soaring bravery – that it would keep the anxiety accelerating.

“The tension in the story is anchored on the affection we develop for these characters,” says McQuarrie. “The suspense lies in witnessing what each and every one of these men goes through in choosing to join the plot, and the decisions they each make in the course of its fateful execution.”

While McQuarrie and Alexander developed a deep respect for those involved in the German Resistance, they also wrestled with how these seemingly principled men of honor served under Hitler in the first place, especially knowing the atrocities of the concentration camps. They note that many of those in the military did not know how inhumane things would become under Hitler until it was too late. These men also took their commitment to the German people – which had been sealed long before Hitler came to power – very seriously. Many of those in the resistance wrestled with how to reconcile their oath with the urgent need to overthrow their country’s leader in a time of war.

“This was a culture where people truly believed that when you gave your word it was for life, and these men had all sworn an oath of loyalty to Hitler,” says McQuarrie. “Yet they ultimately reasoned that Hitler broke his oath to the country with the atrocities he and his ministers were perpetrating. They realized they had to do something for the sake of a different future – even if it meant being vilified as traitors by their fellow countrymen. It was an agonizing moral dilemma.”

Many of the military’s best and brightest hailed from the aristocratic class and were lifelong patriots who had joined the army out of a sense of service during World War I or, like Claus von Stauffenberg in 1926, well before the rise of Hitler. And many of these men were questioning Hitler’s policies by the mid-1930s, as the country’s military aggression and violence against Jews and others expanded. “There was a strong feeling during that time that an aristocrat’s mission should be to serve their country and the people, which is why so many – including Stauffenberg, Tresckow and Olbricht – joined the military,” says McQuarrie. “But many of these men were opposed to the Nazi agenda early on and became increasingly disillusioned with Hitler as the war progressed and they started to learn what was happening to the Jews and the Russians.”

The heinous treatment of Jews, Russian civilians, and POW’s across Europe became a turning point for many, including Stauffenberg. Bryan Singer says, “It was surprising to me to learn from my own research that many members of the military resistance were affected early on and very heavily by the treatment of the Jews and the truth of mass executions. It is what prompted them to feel they had to do something about it no matter the cost.”

Another key to the screenplay’s structure would be revealing the vital importance of Operation Valkyrie, the national emergency plan Hitler himself had established to protect his government from civil unrest if he was cut off or killed. The order called for Germany’s Reserve Army to take command of key government installations until order could be restored – a fact the conspirators cleverly attempted to use to their advantage. By secretly altering this intricate plan, the resistance hoped to assassinate Hitler and take Germany back from the Nazis by installing their own government in the ensuing chaos.

“We wanted to make clear that assassinating Adolf Hitler wasn’t enough, because that wouldn’t guarantee his Nazi government would fall. They also had to find a way to topple his regime,” says McQuarrie. “Stauffenberg and his co-conspirators used Operation Valkyrie to make it look as though Hitler’s closest inner circle had killed him and was trying to take over in Berlin. Posing as the legitimate government, the resistance would quickly mobilize the Reserve Army to arrest Hitler’s cronies and seize control of the government.”

If all had gone off without a hitch, if the plan hadn’t unraveled in so many small but devastating ways, could Operation Valkyrie have succeeded? “I think we can only speculate as to whether it might have worked,” says McQuarrie. “No one can say what exactly would have happened because there were so many different factors at work. But there is evidence to suggest that it could have succeeded. And in the end, I think the conspirators achieved what they had hoped for most: they had shown the world there were Germans willing to make a stand.”

Bryan Singer Takes on a True Story

Many might view Valkyrie as a departure for Singer, but those who know his work best see thematic similarities running through the film. Producer Gilbert Adler, who made Superman Returns with Singer, says, “Stauffenberg is, in a way, a real-life counterpart to what we look for in cinematic heroes: an ordinary man moved to extraordinary actions. Certainly, he was very human and flawed, but I think Bryan brings out that Stauffenberg’s remarkable strength was all grounded in very real things: his dedication to his country, to his family, and especially to what was right.”

Equally important to Singer was capturing the overall atmosphere of Nazi Germany. “Bryan is not only a filmmaker but a real history buff,” says Chris Lee, “and I think those two great passions come through in the level of detail in each frame as well as in the detail in character and emotion.”

For Singer, Valkyrie was a chance not only to take on his first true story but to also explore a period in time that has held a dark fascination for him since childhood, when his Jewish background made him acutely aware of the horrors perpetrated by Hitler and the Nazi government of Germany. “I’ve always had an interest in exploring the Third Reich,” he says. “I touched upon it in a film I did based on a Stephen King novella (Apt Pupil), and again in the first X-Men with the concentration camp scene. But Valkyrie was a chance to segue into a realistic portrayal of that world through an extraordinary true story about a leader who was destroying a country – and much of the world – and the men who decided to try to stop it.”

The very fact that a German resistance existed – and that it even reached into the highest ranks of the military – was something that had long heartened Singer and reminded him of the courage that can come out of basic human decency. “At a very young age, I learned there were Germans who had tried to kill Hitler,” he says. “I didn’t know specifically about Stauffenberg and Olbricht, but I had heard about a bomb in a briefcase, and to me that was always a big deal, to understand that all Germans weren’t Nazis. It would be devastating at such a young age to believe that the whole of a country could be filled with such hate, and it was good to know there were a few who tried to stand against it.”

Singer began doing his own research, reading extensively about every aspect of life during the Third Reich. “One of the first things I did was read The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich by William Shirer, which is an extraordinary book,” he says. “It should really be mandatory reading for anyone trying to understand how an enlightened society can transform very quickly into a killing machine. It goes into the personalities and machinations of Hitler, Göring, Himmler, etc., and it helped give me a deeper understanding of the world the conspirators operated inside. Before I made this movie I needed to understand not just the role of the people trying to remove Hitler, but why Hitler happened in the first place.”

Singer also met with a number of people who could give him an inside perspective. “We had private meetings with members of the Stauffenberg family,” he says. “On the other side, we met with Hitler’s former bodyguard, who, I believe, was the last person to leave the bunker where Hitler committed suicide. These meetings were done specifically to bring new perspectives and ideas to the material. They were very informative, and sometimes transformational in terms of what we learned.”

All of this translated into Singer’s stylistic approach to the film, which would mix nuanced period details of the Third Reich with the lightning pacing and visual dynamism of a modern thriller. Singer says, “We weren’t making a documentary. The important thing was getting the truth of the story across in the most engaging way.”

To this end, Singer made the decision early on to allow each member of the film’s international cast to use his or her own accent. “I’ve navigated through international accents in different ways before, sometimes altering them, sometimes leaving them,” he says. “But with Valkyrie, I had a phenomenal cast playing a fascinating, and sometimes terrifying, group of characters, and I felt it would be stronger to have them use their own natural dialects. When the film begins, you’re transported to this world of German soldiers in the mid-1940s, and the thing that draws you into that world are the characters – these proud military men who saw that they had a monstrous leader and felt they had to get rid of him. The first priority was allowing these characters to come through in strong and very human performances.”

Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg / Tom Cruise

At the center of Valkyrie is Claus von Stauffenberg, the charismatic aristocrat who would ultimately risk everything to carry a bomb into Hitler’s private conference room. But just who was Stauffenberg? After spending months intensively researching his life, screenwriters McQuarrie and Alexander agree he will always remain a somewhat mysterious figure, having been cut down in his prime at the age of 36.

“It’s impossible to fully know Stauffenberg – he’s been left an enigmatic character in history,” says McQuarrie. “Over the years many people have laid claim to Stauffenberg as a poster child or scapegoat for various things, but I think in the end all we can do is look at him for his actions, for the risks he took and what he attempted to do.”

Descended from 700 years of German nobility, Stauffenberg grew up in Bavaria as part of an elite family. Artistically inclined, he loved architecture, music, and poetry, but in the 1920s became a military officer who would soon be noted both for his irascible streak of individualism and his unquestionable heroics. He was said to have been singled out by his superiors for possessing a genius for military organization and logistics, and he rapidly rose in the ranks.

At the beginning of 1943, while fighting in Africa with the Tenth Panzer Division, Stauffenberg sustained severe injuries, losing an eye, his right hand, and several fingers on his left hand. Despite these terrible wounds, he was named Chief of Staff in the General Army Office in the fall of 1943. By then, he had already joined the resistance. On July 1, 1944, Stauffenberg became Chief of the General Staff of the Reserve Army – a job that would take him into direct personal meetings with Hitler. He suddenly found himself in the perfect position to make an assassination attempt on the Führer.

The historian Annedore Leber wrote of Stauffenberg: “[He was] the prototype of those young higher officers who, though their own future careers were never in doubt, nevertheless had the will to take action. They acted from the officer’s sense of responsibility to his troops, the citizen’s sense of responsibility to his people. Even the Gestapo officials who took part in the investigation of the events of July 20 felt a trace of his spirit. They talked of Stauffenberg’s yearning…”

This is also what struck McQuarrie and Alexander about Stauffenberg. Whatever riddles might remain about his life, there is little doubt he was a man of great devotion and ethics. “One of the main things I took away is that Stauffenberg was driven by a deep feeling of obligation to serve his fellow man,” says Alexander. “We can’t know the exact moment he first had grave doubts about Hitler, but once he realized what was going on behind the scenes he clearly believed it was his duty as a German and a human being to take on the responsibility of removing Hitler.”

Stauffenberg is a real-life hero, but in the context of a movie he’s also an incredible character to portray. It’s a daunting role, but the filmmakers felt Tom Cruise was the perfect actor to take it on. “Stauffenberg was an intense, charismatic individual, so we needed an actor who could really portray that,” says director Singer. “I was really excited when Tom came on board. Very few actors are able to pull off those hero roles, but Tom completely does — he’s a highly skilled actor and has such a strong screen presence. Tom also had a passion for this project from the beginning and he believed, like I do, that it’s a story that should be told. He was an important part of getting the movie made, and he and his performance will be a really important part of bringing the story to the world.”

Before taking on the part Cruise hadn’t known that much about Stauffenberg, but to prepare he learned as much about Stauffenberg as he could, and his research and attention to detail quickly showed him what an impressive man he was. “When I first read the script, it was incredibly compelling on many different levels,” Cruise says, “from a historical perspective but also as a great thriller. I was fascinated by the conspiracy. It was dynamic and suspenseful from the opening to the end. Then finding out it was based on a true story – it’s even more mind-blowing. That combination made it very interesting for me.”

The opportunity to work with Bryan Singer is another thing that attracted Cruise to the project. “Bryan is someone I’ve always wanted to work with,” he says. “I think he’s an extraordinary filmmaker. Bryan is someone who even as a kid was making World War II movies. He had an obvious fascination with this time period, and with that kind of interest and dedication you could feel all of us coming together and saying, ‘Okay, let’s make this.'”

Cruise was incredibly moved by what took place inside the German Resistance. “To experience it from Stauffenberg’s perspective and see what these men risked – not just their own lives but their families’ lives – it’s tremendous,” he says. “It’s amazing to see someone under such tremendous pressure stand up for what he felt was right, to have that kind of integrity in those circumstances.”

The actor also found that Stauffenberg’s heroism also hit home in a personal way. “You think, ‘How would I handle that?’, and that’s what makes it very powerful. It’s a timeless movie because it deals with things that are timeless: integrity, heroism, cowardice, compromise. What are you willing to stand up for or not do anything about? These are questions that we as human beings evaluate in our own lives.”

“Ultimately, I don’t think Stauffenberg saw himself as a hero,” he continues. “He saw it as the correct thing to do, to try to end the war and spare human lives. Stauffenberg is someone who really always drove himself towards a higher moral ground and searched for moral correctness and rightness for himself, and he wanted that for his country. He was one of the few that had the courage to stand up to Hitler and even be willing to sacrifice his own life to try and get that done.”

To play Stauffenberg, one of the challenges Cruise had to face was Stauffenberg’s physical scarring from his injuries in North Africa, including wearing an eye patch. “The eye patch was very difficult,” he says. “At first it threw my balance off, and I would imagine the kind of physical discomfort he had to live with. It was also challenging from a performance point of view, how to communicate as an actor with part of your face gone.”

Wearing Stauffenberg’s uniform also proved difficult. “Putting on that uniform and looking at the world from that perspective was disturbing,” he says. “I didn’t like it at all. It definitely changes your viewpoint. Then looking at it from Stauffenberg’s viewpoint and what it meant to him to wear that uniform and the conflict he had – it helped me very much.”

In addition to the real-life aspects of his character, shooting in Berlin was very powerful for Cruise, as well as the entire cast and crew. “It’s hard to describe what it was like standing there at the Benderblock,” he says. “It affected all of us to be there and think about what had actually happened where we were standing.”

“Tom brings an incredible intensity, poise, and focus to the role, and more than anything, he brings the charisma I think the character required,” says McQuarrie. “When Tom Cruise walks into a room, you have a sense of the charisma Stauffenberg might have had. What Tom also brings is his experience as a filmmaker and storyteller. The script only got better, the character only became clearer, our understanding of the history and our understanding of where we were in this universe, it all only became clearer as a result of Tom being involved.”

In the end, with all the hard work that went into the film and the incredible experience of making it, Cruise is very pleased with the end result. “The film is a ticking clock,” he says. “This is a dynamic suspense thriller that will keep you on the edge of your seat all the way through. I’m proud that we got the film made, and I’m very proud of what everyone accomplished.”

When she married handsome, aristocratic Claus von Stauffenberg in 1933, Nina von Stauffenberg, a baroness, could not have known the sacrifices she would ultimately make for her beloved husband and country. Though she was never directly involved in the plot against Hitler, she and her family were among her husband’s strongest inspirations and she remained his confidante and unwavering supporter throughout the build-up to the assassination attempt.

Ultimately, Nina would be one of the few to survive the events of July 20. She was imprisoned in the Ravensbrück concentration camp (where she gave birth to her fifth child with Claus), then after the war she and her family built new lives in West Germany where she lived until her death in 2006 at the age of 92.

While researching the screenplay, McQuarrie and Alexander wanted to determine whether or not Nina knew what Claus was about to do that fateful summer. “It became pretty clear that she did know and supported his plan in every way that she could,” says Alexander. “Nina wasn’t involved in the details, but I think you still have to look at her as an important member of the conspiracy. She had as much to lose as any of them. Later, when we spoke to members of her family, we were left with the impression that while Nina and Claus never spoke directly about the plot, in a sense it was all they talked about. Their love story is crucial because at its center lies what was truly at stake for Stauffenberg: his children and the future of Germany.”

Playing Nina is Carice van Houten, the stunning Dutch actress who came to global attention with her award-winning role in Paul Verhoeven’s thriller Black Book. “We were all immediately struck with Carice when we saw Black Book and said, ‘That’s Nina,'” says McQuarrie. “She has these scenes where she says very little yet completely fills the screen with her presence. She’s an extraordinarily generous actress.”

What intrigued van Houten was the chance to bring a woman’s perspective to the heroics of the July 20th plot. “I loved that in the midst of this exciting story of conspiracy, you also see Claus and Nina’s family life,” she says. “Nina might not have a lot of words in this story, but she brings a lot of feelings.” Van Houten also sees Nina as revealing a different face of courage and commitment. “I think she had to find her own strength to show this unconditional love and give her husband the freedom to do this incredible thing without fear,” she says. “Nina understood what they were doing was not only about trying to save their family but also the country and the world.”

Major-General Henning von Tresckow / Kenneth Branagh

Today, Henning von Tresckow is renowned as one of the most driven and unrelenting enemies of Hitler inside the German armed forces. A member of a noble Prussian family with a long military history, he was considered a brilliant strategist with a long record of distinguished service in Germany. But as early as 1938, Tresckow began seeking out other military insiders as well as civilians who opposed Hitler to start exploring means of overthrowing the government. He is perhaps best known for his attempt, seen in Valkyrie, to smuggle captured British adhesive mines (“clams”) disguised as two bottles of Cointreau onto Hitler’s airplane.

Tresckow’s role in the screenplay was key. “Before Stauffenberg became involved, Tresckow was the engine driving the military resistance to Hitler and it was important that be emphasized,” says Alexander. “His beliefs and ideals help shape the heart of the movie, as he always maintained it didn’t matter if the conspirators failed, what mattered was that they try.”

Playing Tresckow is four-time Academy Award nominee Kenneth Branagh. “Branagh has this incredible bearing that really sets the tone of all that’s at stake in carrying out the plot to overthrow Hitler,” says Chris Lee. It was the script that lured Branagh, himself a highly accomplished screenwriter. “My palms were sweating with excitement over what might happen next,” he recalls of his first reading. “And the characters, including Tresckow, were so compelling and hypnotic. It reveals a secret part of World War II – that there were those who were philosophically, intellectually, and militarily in disagreement with Hitler and that, though they were often suppressed, their voices were there.”

Branagh was impressed with the distinctive tone of Valkyrie. “Chris McQuarrie and Nathan Alexander have a very strong, naturalistic style of dialogue and Bryan Singer was very attuned to that naturalism,” he says. “What he wanted from the performances is that these men be human beings. Not archetypes or stock characters, but flesh and blood heroes represented as truthfully as possible.”

Branagh was also thrilled to be a part of an incredibly accomplished international cast. “The strength and depth of this cast made it a real privilege to be a part of it,” he concludes. “But it’s no surprise. The story is so strong and Bryan Singer is such a terrific director, it’s no wonder so many very talented people joined up.”

Like Henning von Tresckow, Friedrich Olbricht was a military hero who had been awarded the Iron Cross and served as leader of the General Army Office in the Army Leadership High Command. By 1940, he had joined the resistance and was secretly working to overthrow Hitler. It was Olbricht who was given the daunting responsibility of putting Operation Valkyrie into motion on July 20. On the eve of his death, Olbricht would write to his son-in-law: “I will be dying for a good cause; of that I am firmly convinced. Should we now make out that we have sinned? No, we have dared to do the utmost for Germany.”

In the film, Olbricht’s moment of hesitation under fire becomes one of several twists of fate that threaten the plan to use Operation Valkyrie to overthrow Hitler’s government. Yet, Olbricht remains a highly sympathetic character.

“We wanted to avoid making Olbricht into the fall guy,” says McQuarrie. “He was a human being who had reasons for acting the way he did and we felt it would have been crass to use him merely as a device. It was real challenge to do this, and the casting of Bill Nighy completed it because he is such an eminently sympathetic person and he was really able to convey Olbricht’s extreme stress and anxiety.”

Olbricht is brought to life by Golden Globe winner Bill Nighy, whose alternately comic and nuanced performances in such films as Love Actually, The Girl in the Café, The Constant Gardener and Notes on a Scandal have made him one of today’s most diverse and sought-after screen actors. Nighy says he found the story of Valkyrie, “astonishing in itself but also in its dramatization. It worked on several levels, not least of all as a nail-biting thriller, all made even more fascinating by dint of the fact that it’s true.”

Nighy was intrigued to learn just how deep the resistance to Hitler actually ran among some German officers like Olbricht. “People like Olbricht were deeply ashamed to be associated with this buffoon and they also deeply grieved the loss of men caused by these reckless military campaigns,” he observes. “But it is one thing to observe and complain about it, and another to decide to do something about it, which is an extraordinarily brave thing given how efficiently the Nazis dispatched their enemies.”

As for Olbricht himself, Nighy wanted to reveal his finest qualities as well as the questioning nature that might have fatefully delayed Operation Valkyrie. “The challenge for me was to show an honorable, brave, clever man who, at just one single point, is undermined by the situation to the point where he can’t quite act. It was important to me to show a great amount of respect to him and to give his situation dignity and humanity,” says the actor.

For the filmmakers, Nighy was an inspired piece of casting. “We’re used to seeing him in lighter parts, but here he plays a hard-edged man with a hint of real vulnerability. I have to admit the first time I saw him in uniform as Olbricht I had chills. He really became the part,” says Gilbert Adler.

General Ludwig Beck / Terence Stamp

Though he served as Chief of Staff for the German Army from 1933 to 1938, General Ludwig Beck quickly became an open and unusually vocal critic of Hitler’s military strategies. Following his conscience, he wrote a memorandum taking a strong stand against Hitler’s policy of aggression and resigned his post. Unsuccessful in a plan to get other military higher-ups to resign in a group and thus launch a coup d’état, he then began developing an underground network of military and civilian agents who helped to form the central German opposition. It is believed that Beck would have been head of state if a coup had succeeded.

“Beck recognized Hitler very early on for what he was,” says McQuarrie. “He disagreed with his policies and chose not be a part of his Army. He became something of an advisor and counselor to those who were dealing with a crisis of faith, who were struggling with the oath they had taken to their leader. And a great many of those people who came to him for counsel ended up as members of the plot to remove Hitler from power.”

To portray Beck, the filmmakers chose Academy Award nominee Terence Stamp, known for decades of richly layered performances (and most recently a comic turn in Get Smart). Stamp says that Beck interested him because “he was one of the first people to not only see that Hitler was a lunatic, but to do something about it.”

Stamp was also drawn in by the film’s extraordinary ensemble. “Every one of these actors has really earned their spurs,” he says. “They’ve all done every kind of role, they’re totally confident, and the casting was spot on.”

General Friedrich Fromm / Tom Wilkinson

Claus von Stauffenberg’s superior throughout the events of 1944 was Friedrich Fromm, the Commander in Chief of the Reserve Army. Though there is little doubt that Fromm knew men beneath him were planning an assassination of Hitler, he remained silent and did nothing to stop it. Yet when the conspiracy failed, it was Fromm who betrayed Stauffenberg and the others.

In order to portray Fromm, the filmmakers cast two-time Academy Award nominee Tom Wilkinson in the role. “Tom Wilkinson took a role that could have very easily been portrayed as a villain and instead portrayed him as a product of an extremely duplicitous, treacherous environment. He is a political maneuverer trying to survive in this world, and he’s played brilliantly,” says Christopher McQuarrie.

General Erich Fellgiebel / Eddie Izzard

A career officer, Erich Fellgiebel was chief of the Army Signal Corps and thus privy to many of the most sensitive secrets of the Nazi government. Recruited into the resistance by his senior officer Ludwig Beck, Fellgiebel became an integral link in the conspiracy plot of July 20th – and was handed the vital task of cutting communication from Hitler’s Wolf’s Lair to the rest of Germany. He would later be one of the first conspirators arrested.

Taking on this role is British actor Eddie Izzard, who recently made his U.S. TV debut with The Riches. “Eddie is far from the most likely choice to play this character, but that’s what we liked,” notes McQuarrie. “His performance was quite unexpected. Fellgiebel is struggling with a decision, and we wanted him to be hard to read so you wouldn’t know his decision until the moment he made it. Eddie was able to do that.”

Izzard, long a history buff, was intrigued by Fellgiebel. “He’s a career officer who’s done well and is brilliant at setting up the new technology for communications,” he says. “By the time we meet him in 1944, he is in charge of all of Hitler’s communications, so he knows everything that’s coming and going – which means that Stauffenberg needs him. I think it was a chance for Fellgiebel to clear his conscience somewhat by being part of this action.”

Once on the set, Izzard was thrown right into the fire – his first scene was the gut-wrenchingly tense moment when Tom Cruise as Stauffenberg takes a chance by inviting Fellgiebel to join the secret conspiracy. “I had the uniform on and the hair and the glasses and then Tom comes in and he has so much intensity, I had to find a way to spin into all of that,” he says. “It was a tough first day because every line Tom has is just batting it back to me – every angle Fellgiebel tries to use, Stauffenberg has already thought of a counter-argument.”

Lieutenant Werner von Haeften / Jamie Parker

The person who quite possibly had the most intimate view of Claus von Stauffenberg in the days before July 20th was his personal aide. Werner von Haeften began working for Stauffenberg in 1943 and soon became an integral part of the resistance himself. Haeften had studied law before joining the army in the early days of the war. Like Stauffenberg, he was severely injured in battle. To play Haeften, the filmmakers turned to rising young British star Jamie Parker, who recently came to the fore onscreen reprising his Broadway role in “The History Boys.”

“Jamie is a terrific young actor who plays a sort of Everyman in the movie very well,” says Chris Lee. “He becomes a kind of surrogate for the audience as the new kid on the block who gets to know the resistance as we watch.”

Parker liked having the chance to show his character’s path to becoming part of the conspiracy. “At first, he’s just listening and observing all that’s going on around him, but as he becomes more and more involved, you get to see that process,” says Parker.

Working with Tom Cruise was also an incredible experience for Parker. “When I first got to the set, I had a sort of minor meltdown, thinking ‘that’s Tom Cruise, who I’ve seen in an awful lot of films,'” he says. “But he turned out to be an extraordinary bloke. He has unlimited energy and he’s willing to go for it right from the word go. He brought a real focus to the work ethic every day and you can’t help but be affected by that. It requires that you’re always switched on, and it was an exciting experience.”

Recreating the Berlin of 1944: The Design of Valkyrie

From the beginning, Bryan Singer knew he wanted VALKRYIE to defy the usual look and feel of a film set in the World War II era. He envisioned a visual style that would echo the moody beauty and intensity of classic films of the 1940s yet would rocket with the pace and tempo of a modern action-thriller. Quite early on he began consulting with long-time creative collaborator director of photography Newton Thomas Sigel on how they would create this on screen.

Sigel most recently worked with Singer creating the comic-book worlds of X-Men and Superman Returns and he was excited to face a completely different challenge. “Instead of worrying about green screens and wire removal, we were going to be capturing history,” Sigel says. “I was very excited because I’m fascinated by history and politics and the social mechanics of the world, and it was great to make a film with Bryan about all of those things.”

There was also a strong personal connection in Valkyrie for Sigel. “My mother was born in Berlin and fled in 1938 right before Kristallnacht, so on an emotional level the story resonated very deeply for me,” he says. “Working on this film gave me an opportunity to talk to her about things I’d never heard from her before.”

Sigel and Singer discussed finding a distinctive but understated look for the film that would allow the anxiety and emotions of what these imperiled conspirators were experiencing to come to the fore. “We mixed the classical look you see in some of the films from that period – with their more formal framing and weird oblique angles – with elements of a contemporary thriller,” he says. “I’m usually very impressionistic in my style, but we held back more on this film. We felt strongly that we wanted the visual style of the film to be very respectful of the reality of these events and the sacrifices made. The lighting, the angles, the relationship between camera and subject – they always had to be one of singular and simple truth.”

They also determined the camerawork would subtly evolve from the first half of the film when the plot is in its planning stages to the latter half when the plan to assassinate Hitler is in full motion and stakes are ratcheted to relentless levels. “The beginning of the film, before the bomb goes off in Hitler’s [conference hut], is done in a more classical way, with cranes and dollies and more formal, fluid compositions,” Sigel says. “But after that, it’s almost entirely hand-held. We used a particular kind of hand-held work with the cameras on the shoulders that feels almost like a hand-held dolly. The result creates a kind of subtle nervous energy, a feeling of uncertainty, increasing the suspense and anxiety.”

To delve deeper into recreating the inner world of the Third Reich, Sigel watched lots of old footage, including recently discovered color film from World War II and eerie home movies shot by Hitler’s mistress, Eva Braun. “The footage was very helpful in giving me a sense of the way people moved and dressed and the feeling of the atmosphere, which is something we wanted to authentically capture,” he comments.

In terms of palette, Sigel focused on varying shades of red. “Red was really the symbolic color of the Nazi Party and I think it represents the primal bloodthirstiness of this regime,” he says. “Like the camerawork, the colors get more intense as the film progresses, and you also see some of the warmth and optimism of the conspirators start to fade.”

Lighting challenges were another major element of the photography, particularly because Singer and Sigel hoped to recreate the tense, shadowy feel of Berlin at night, where citizens were told to keep all lights out and curtains drawn in case of sudden bombing raids. “That was one of our biggest challenges, because the city had to be very dark at night,” says Sigel. “In fact, the city was so dark they actually were said to have used a car’s headlights for the executions at the Bendlerblock, so that’s what we tried to recreate for those scenes.”

Some of Sigel’s greatest inspiration came from working in Berlin itself, surrounded by the ghosts of history. “To be in Berlin where these events really happened was incredible, because it wasn’t like you were one step removed. Even though most of locations from 1944 no longer exist, you still feel the presence of the war everywhere. It gave us a great sense of awe over the principles people laid their lives on the line for,” he says.

Shooting in Germany, and especially at the Bendlerblock – the military headquarters where Operation Valkyrie was born and came to its fateful conclusion – was a highly emotional experience for everyone in the cast and crew. “It was truly moving to shoot in the Bendlerblock,” says McQuarrie. “We first had a moment of silence in honor of the men who died there before reading a letter written by one of the conspirators. In it, he expressed his hope that they would be seen as patriots and not as traitors. We were surrounded by deep emotions over what we were commemorating.”

The film’s production design was overseen by two-time Academy Award® nominee Lilly Kilvert and co-production designer Patrick Lumb, who had an unusual mandate: maintaining a look accurate to the period while keeping it dynamically alive with tension. They were also faced with the substantial task of recreating Nazi-era Germany in a Berlin that had to be entirely rebuilt after the war because of extensive bombing – and because Germans were very careful nothing from the era survived to become a shrine.

The production was able to find some civilian and government buildings in the story still in existence. Filming was done at the former Luftwaffe headquarters, now the Ministry of Finance; at Tempelhof Airport, where there is a large structure that was used by the Nazis; and also at the Messe Berlin, which was originally built by the Nazis for the World’s Fair in 1933. They were also able to shoot the exterior of the house where Stauffenberg lived with his brother, which remains standing.

For locations that had to be recreated from scratch, the team looked to the works of Hitler’s architect, Albert Speer, who would later be the only senior Nazi government official to express remorse. Speer was commissioned by Hitler to create grandiose, imposing buildings that would reflect the Nazi philosophy in stone, so it was a challenge to recreate interior rooms that showcased the impressive scale he preferred.

Among the most difficult buildings to recreate was Hitler’s home and headquarters in the Bavarian Alps, known as “The Berghof.” Using home movies shot by Eva Braun, the design team was able to simulate the interiors of the chalet-style retreat that was devastated by the allies and ultimately torn down. For the recreation of the Wolf’s Lair, Hilter’s massive hideout in East Prussia where the July 20th plot took place, it took the crew about 12 weeks to build the set from scratch in a forest. All recreations were done with an eye towards making things as accurate and true-to-history as possible.

The result was transporting. “Looking at what the designers had done, for a minute I felt I was there where Hitler and Stauffenberg took their historic picture together. I was thinking to myself ‘this is not real, we built this,’ but it felt completely real,” says Gilbert Adler.

Meanwhile, the interior of the War Ministry, including the offices of Stauffenberg, Olbricht, and Fromm where the plot is first hatched, was built on a soundstage at Berlin’s Babelsberg Studios.

Dressing the film’s interiors involved further detective work. It’s illegal to have anything with a swastika on it in today’s Germany, but set decorator Bernhard Heinrich managed to collect artifacts from collectors and museum all over the world, including authentic pieces that were actually on Hitler’s desk.

Dressing the Third Reich: Joanna Johnston’s Costumes

Equally key to the design of Valkyrie would be the costumes, which Bryan Singer wanted to be as authentic to the Nazi Era as possible while still being richly cinematic. He brought aboard costume designer Joanna Johnston, who is renowned for her work with Steven Spielberg, including the costumes for his WWII epic Saving Private Ryan.

Johnston knew going into Valkyrie that films involving historical military uniforms are an experience unto themselves. “It takes you into a whole different mind set,” she says. “But with Valkyrie, I was especially excited about the challenges because there was an opportunity to learn so much about this fascinating time period.”

Johnston worked closely with military uniforms advisor David Crossman, and also delved into her own research, which she culled from the Museum of the Resistance in Berlin as well as from the limited but indispensable photography available of most the real-life characters depicted in the film. In the photos, she found crucial insights into the characters’ personalities. “I studied the textures and nuances of each of the characters very closely,” she says. “What was intriguing to me is that you might expect they would look very cookie-cutter and similar. But in fact, German officers had great leeway in their dress. They each went to their own personal tailors and thus each had their own individual quirks. Tresckow might do one thing with his uniform and Olbricht another. My springboard was blowing up these tiny photos and using small, subtle textures to reflect the differences in tone and character.”

She received great support for her approach. “Bryan and Tom were as keen as I was to do something that hadn’t really been done before, to give this period and place a texture and life that audiences haven’t seen,” she says.

Most of the exquisitely detailed clothing for the main characters was made by hand for the film with the help of Michael Sloan, whom Johnston calls “a brilliant cutter.” But vintage uniforms were also proffered for the large, secondary cast. “It was very useful to have so many original garments,” says Johnston. “You really can’t beat the originals, because they have a certain cut and shape to them, and they also resonate of enormous gravitas when you think of who might have worn them and what they might have witnessed in them.”

The core of Johnston’s work was creating Stauffenberg’s wardrobe, which she notes runs a wide gamut from his Africa Corps uniform to his standard field grays to his lighter summer grays and the highly ornamented outfit he wears when going to meet Hitler. “We only had a few photographs to work from, so we designed everything based on what we suspected he would have worn,” she explains. “We kept in mind a word that was used to describe his style: irreverent. He often didn’t wear all his insignia. He took the stature out of his clothing by keeping it bare bones to not draw attention to himself.”

Stauffenberg’s injuries, especially his missing hand, added an additional layer of difficulty. “At first, there was a lot of complicated discussion about how to authentically depict the hand,” she says. “Ultimately, we decided to use digital special effects, but there were still issues we had to address. I had to pay great attention to the behavior of his sleeves, because there always had to be a sense of emptiness there. Tom was a tremendous help here because he was effective at keeping his arm so still and dead.”

Johnston took a bit more creative license with Nina. “She was certainly a beautiful woman who had a great sense of style,” she says, “but I also wanted to do something a little romantic with Nina. I used a greater richness of color to play against the stark background of German uniforms, and also emphasized movement whenever she is running or dancing.”

The most daunting character of all for Johnston was Hitler, played by David Bamber. Throughout cinematic history, Hitler has often been depicted as a cartoonish caricature. Johnston wanted to avoid all the clichés, while also reflecting the reality of Hitler in 1944. “We are in Hitler’s decline at this point in time,” she points out, “so he’s starting to crumble. He’s thickened out a bit and he doesn’t have quite the same strong presence he had in the early days of his power. Bryan was really keen to get that aspect of him right. We had a lot of meetings and fittings with David Bamber to assure it would feel very real.”

When Bamber appeared on set in the final uniform, the effect was chilling. “It was pretty unsettling,” admits the designer. “When you’re designing, you look past the big historical picture in order to focus on the intimate details, but then when you see this reality in front of you it creates a lot of emotions.”

The process of clothing each member of the resistance was similar, with the clothes transforming the actor and vice versa. “The German uniforms have a very strong look – with the britches and boots, with their sense of both power and tragedy – and each actor brought it off quite differently, in his own way, which was a fascinating exercise to observe,” says Johnston.

Says Bill Nighy, “The importance of the clothing can’t be overstressed. To put on something as deeply unsetting and formal as a military uniform makes you hold yourself in a different way, and your behavior is profoundly informed by what you’re wearing.”

Johnston says, “As with Saving Private Ryan, it was a privilege to be part of something that felt like more than just a film. It’s a story that honors incredible people and gives you a broader perspective on life.”

A Brief History of the German Resistance to Hitler

One of the lingering myths of the World War II era is that all Germans were Nazis loyal to Adolf Hitler. This was not the case, as there were a number of groups who both secretly and openly opposed the regime of Adolf Hitler after he first came to power in 1933. These included student groups (including the famous White Rose resistance group, who risked and gave their lives to distribute leaflets condemning the Nazi Government and calling for its overthrow), religious groups, and a variety of political groups, including socialists and communists, who defied the rise of Nazism, inviting imprisonment and execution. Sophie Scholl and her brother, Hans, were beheaded for their roles in the White Rose.

As Hitler’s ambitions for the country broadened and the grotesque machinations of the Holocaust were put into motion, there were also a number of brave, conscientious individuals who committed singular acts of resistance, hiding and helping Jews to escape and providing intelligence to the Allies as well as refusing to cooperate with Nazi orders. Some such as Oskar Schindler and Pastor Niemöller became legendary.

But perhaps the least known, and most powerful, members of the German Resistance remain those who were committed to fighting Hitler from inside the system – military and high political office holders who dreaded what was happening to their country and attempted to hatch conspiracies to do the only thing that could alter the future: overthrow the government. The motives of those involved were probably quite varied. Some merely hoped to install a less dangerous dictator, others hoped to change Germany’s entire political system, and still others were driven largely by humanitarian concerns. Yet each was convinced that Hitler was a disaster for the country and needed to be stopped no matter the cost.

As early as 1936, there is evidence that German officers under the leadership of then Lieutenant-Colonel Hans Oster were planning to assassinate Hitler. In 1938, a group of conspirators including General Ludwig Beck (who would later be a key player in the July 20th plot) planned to arrest and imprison Hitler on the eve of war, but the plan fell apart. A significant attempt on Hitler’s life came in 1939 when Georg Elser, a carpenter, stole explosives from his workplace and built a powerful time-bomb, which he hid in a pillar near a podium where he knew Hitler was to speak. The plan nearly worked. But when Hitler’s speech ended earlier than expected, the bomb went off too late, killing eight bystanders. Elser was arrested in November 1939 and executed at Dachau two weeks before its liberation.

Another assassination attempt in 1943, depicted in the film, was plotted by Henning von Tresckow. Tresckow had persuaded a member of Hitler’s staff, Lieutenant-Colonel Heinz Brandt, to carry a package onto Hitler’s airplane containing two adhesive mines (“Clams”) with a time-delay fuse, disguised as two bottles of Cointreau. But once again, luck was on Hitler’s side, as the bomb failed to go off, probably because the freezing conditions in the cargo bay left its chemical detonator powerless. Tresckow was undetected as the source of the bomb, allowing him to continue to seek a method and means to assassinate Hitler.

This ultimately culminated in the July 20th plot, which was by far the most ambitious of all the conspiracies against Hitler, not just because it was a plan for assassination but because it was a blueprint for overthrowing and replacing the entire Nazi government. In the short term, the plot’s fateful end destroyed the entire network of anti-Nazi conspirators within the government machinery. Approximately 200 persons were hanged for their involvement, 700 were arrested in direct connection, and 5000 were arrested in August 1944 as potential “enemies” of the Reich. (Executions of those who took part in the plot continued right up to the very last days of the war.) In the long term, however, the plot revealed a side of Germany that had been largely unknown, inside and out. Although regarded as traitors for many years, those who planned the July 20th plot are recognized in Germany for their courage and sacrifice. In 2004, then German chancellor Gerhard Schröder laid a wreath for Claus von Stauffenberg and his co-conspirators, saying that their actions were a reminder that a nation must “again and again defend the values of freedom and tolerance that we consider self-evident today.”

Timeline

January 30, 1933 Hitler is appointed chancellor of Germany.

June 30, 1934 Night of the Long Knives: Hitler has SA leaders murdered when they threaten his control, and other political opponents are killed in the same sweep.

August 18, 1938 Chief of General Staff Ludwig Beck resigns, protesting Hitler’s military aggression and warning of catastrophe.

Summer 1938 Lieutenant-Colonel Hans Oster organizes a military and civilian network focused on assassinating Hitler. Their plans, however, fail.

November 9, 1938 Kristallnacht: Widespread violence spreads against German Jews.

September 1, 1939 World War II begins as Germany invades Poland.

November 8, 1939 Georg Elser attempts to kill Hitler with a bomb, but fails.

Summer 1941 Henning von Tresckow begins organizing a resistance within the Army Group Center.

March 13, 1943 Tresckow’s timebomb in Hitler’s airplane fails to explode.

April 7, 1943 Claus von Stauffenberg is severely injured in Tunisia.

January 24, 1943 Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill demand the “unconditional surrender” of Germany.

Summer 1943 Tresckow, Friedrich Olbricht, and Claus von Stauffenberg begin to alter Hitler’s Operation Valkyrie in preparation for a coup.

October 1943 Stauffenberg named chief of staff of the General Army Office under Olbricht.

July 11, 1944 First plan to assassinate Hitler by Stauffenberg is aborted.

July 15, 1944 Second attempt to assassinate Hitler at the Wolf’s Lair is aborted.

July 20, 1944 Stauffenberg sets off a bomb at the Wolf’s Lair and the coup attempt begins.

That same night, Stauffenberg, Olbricht, Albrecht Mertz von Quirnheim, and Werner von Haeften are executed by firing squad in the courtyard on Bendlerstrasse.

April 30, 1945 With the war all but over, Hitler commits suicide.

May 8, 1945 Germany surrenders unconditionally.

Valkyrie (2008)

Starring: Tom Cruise, Kenneth Branagh, Bill Nighy, Tom Wilkinson, Carice van Houten, Halina Reijn, Christian Berkel, Terence Stamp, Thomas Kretschmann, Kevin McNally, Tom Hollander

Directed by: Bryan Singer

Screenplay by: Nathan Alexander, Christopher McQuarrie

Production Design by: Lilly Kilvert, Tom Meyer

Cinematography by: Newton Thomas Sigel

Film Editing by: John Ottman

Costume Design by: Joanna Johnston

Set Decoration by: Bernhard Henrich

Music by: John Ottman

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for violence and brief strong language.

Distributed by: Metro Goldwyn Mayer

Release Date: December 25, 2008

Views: 131