World Trade Center Movie Trailer. Overseeing the production was Don Lee, a veteran producer and native New Yorker who witnessed 9/11 firsthand. “I live downtown and was on my way to jury duty when I saw the second plane hit,” Lee remembers. “The story of these two men appealed to me because it was about New Yorkers helping New Yorkers – two regular guys who went in and almost lost their lives trying to save people.”

According to Lee, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey gave unprecedented support to the production. With the filmmakers’ commitment to authenticity a top priority, the Port Authority’s cooperation proved invaluable. Not only did they allow the company to film at the Port Authority bus terminal for three weekends – a first for the Authority – but the agency served as advisers to the prop and wardrobe departments on the appropriate gear.

“The PAPD made it possible for us to go directly to their vendors so that everything was authentic,” says propmaster Daniel Boxer. In addition to authentic emergency uniforms, the production was able to purchase 75 FDNY radios, six dozen Scott Air Paks, three dozen PAPD gunbelts, a stock room full of police department batons, plastic replicas of period-correct Smith & Wessons pistols, handcuffs modified for movie use, and ca. 2001 signage and graphics.

One of the first “sets” within the Port Authority was in the cops’ real locker rooms in the basement. In fact, it was in this room where Jimeno, Rodrigues, Pezzulo, and their colleagues gathered every day, before and after work, and talked and razzed each other, a scene Stone recreated in the movie. A portion of the locker room was dressed for the “period” – no iPods, different cell phones, newspapers with appropriate headlines – and otherwise rearranged to accommodate cameras, lights, gear and personnel. However, the perimeter remained untouched, and on the beaten lockers hung memorialized “legacy” photos of the officers who lost their lives on 9/11.

“It was a very moving experience to shoot down in those lockers,” says Jay Hernandez. “I saw Dominick’s locker; his picture was up on it like a shrine and it brought back a lot of the emotions that I experienced on that day.”

“You have to be on top of everything going on around you to be a police officer,” says Peña, who spent time with PAPD officers as he prepared for the role. “Those guys are intense. I remember, we were walking through the bus terminal, and they picked one guy out of the crowd – looked like just another guy to me. They asked him what he was doing and he said, `I’m sorry, man – I’ve been hustling.’ Just tells the cop everything! It doesn’t show up in any arrest statistics, but that cop stopped a lot of crime right there. It was really helpful to see firsthand what those guys do.”

About the Production

To bring McLoughlin’s and Jimeno’s story to the screen, Oliver Stone brought together an outstanding team of professionals. The director of photography is Seamus McGarvey, who filmed the Academy Award nominee for best picture, “The Hours.” Jan Roelfs, the production designer, is a two-time Academy Award nominee and previously worked with Stone on the epic “Alexander.” Editor David Brenner, who won the Oscar for his work on Stone’s “Born on the Fourth of July,” marks his eighth collaboration with the director, joining with his longtime assistant and now fine lead editor in her own right, Julie Monroe. The costumes are designed by Michael Dennison. Composer Craig Armstrong, who has provided the music for such diverse films as “Moulin Rouge” and “Ray,” writes the score.

Although several of Stone’s movies feature operatic camerawork, “World Trade Center,” by comparison, is visually spare. “Seamus and I agreed early on to go more conservatively on this movie, to keep the moves simple, especially in the holes where the men are buried,” says Stone. “And to concentrate on the lighting. We wanted to keep the balance of realistic shadows, yet see into their eyes. Outside the holes, we sought the light as much as possible in the story of the wives and the Marine, to alleviate the dark. In the end, we played off the light and the dark, with variations, seeking to reverse the normal functions of both.”

With that in mind, McGarvey and Stone designed the camera work to convey the characters’ internal emotional journeys. “Oliver’s way of considering the lens is amazing. He is very, very precise with what the camera says and what the camera movement means,” says McGarvey. “He is never flagrant with the moves and he always captures great performances. Although we used a more naturalistic mode, there was a vibration throughout that is the director’s voice, the voice of an auteur and it created a unique quality. As in all his films, Oliver has identified with the protagonists and their dilemmas, their pain and their hope.”

To achieve that vision, McGarvey embarked on a testing process on the best ways to pick up emotion through shifts in light and focus. “On every film, you find something that offers a way of expressing emotion photographically. I asked Panavision, `I’m trying to focus in on a single plane, on an eye or a mouth, trying to explore the landscape of the face without a camera move. Have you anything like that? They told me, `We’ve got the perfect thing.’”

The perfect thing turned out to be a prototype of a lens invented by Steve Hylen, the designer at Panavision, which allowed McGarvey to control and train the lens on certain points of the face as the emotion of the scene dictated. “We used it sparingly, at fairly critical junctures, where we were on the protagonists’ faces and as we close in on an eye or a mouth, we can redirect the audience’s attention. It was incredibly subtle when we’re signaling a memory,” McGarvey says.

“I find that most scripts have a photographic heart and this one certainly had a very strong visual identity,” McGarvey concludes. “It’s spare, not highly stylized. Also, there are parts of the story that have a very subjective quality, in that you see it from the characters’ perspectives. Increasingly, as the story progresses, it becomes more transcendent. We devised ways of expressing that visually.”

The construction department began resurrecting the World Trade Center while the shooting crew filmed in New York, in order to have it ready by the time Stone returned to California. Devising the set was a challenge for production designer Jan Roelfs because the collapsed towers were very well documented in photographs and on television. While this offered a plethora of research material, it meant that everyone in the world had seen and remembered the original and no mistakes could be made. Moreover, Roelfs had to configure a construction that could accommodate the needs of the camera and lighting crews, as well as the creative requirements of Oliver Stone.

“I knew what Ground Zero looked like, but how to make it into a set that was shootable and affordable? That was one of the biggest challenges,” Roelfs says. “There was so much documentation of the Ground Zero site so that was very helpful, but, it spanned over 16 acres and that was too massive to build to scale. We started with models. As the set began to take shape, it was clear that there were certain iconic pieces that we would use as landmarks, stark pieces of the buildings that remained standing that were in many of the photographs. Then we had to build it and make it camera ready but also safe.”

Roelfs and his team constructed the set at the former home of Hughes Aircraft in Playa Vista. They began with Styrofoam reinforced with a urethane coating to make it strong but supple. Then, the art department was able to augment the Styrofoam beams with pieces of twisted metal procured from area scrap metal dealers. By the end of construction, the set contained 200 tons of scrap metal and 900 individual sculpted pieces and spanned about an acre, 1/16th of the original rubble field.

One of Roelfs’s ingenious moves was driven by necessity: because Stone’s artistic vision demanded that the set be lit and shot from below and above, the massive set could not be built on the ground; it had to be perched on some structure. Instead of building an elaborate base, he decided to rent a large quantity of shipping containers and built the set on top of them. “Because we were in Playa Vista, we had easy access to the port of Long Beach, which is the biggest container harbor in America,” Roelfs recalls.

The combination of containers, wood and steel struts, and platforms not only provided a level, sturdy plane for a giant crane, dolly tracks and other assorted camera necessities, it also created a labyrinth of tunnels and walkways beneath the shooting area. This offered shortcuts across the set and places to stow gear and, importantly, it enabled Chief Lighting Technician Randy J. Woodside to light it.

“We shot much of Ground Zero at night, because that’s when Will was rescued. That first night, after the Towers collapsed, there wasn’t much light; the site was mostly lit from the ground and some emergency equipment. We had to light a movie set, but essentially, it was the same concept: the set was lit from low angles and we had one large backlight from behind to provide shards of light,” Woodside says.

Woodside, like all the cast and crew, says that when he first saw the sets, “I was at a loss – they really impacted me emotionally, more than I expected, more than any other movie I’ve ever done. It was hard to direct my crew where to go on the set – we just had north, south, east, and west as reference points. I can only imagine what the rescuers when through when they were combing the real place, looking for survivors.”

When designing this set, Roelfs queried McLoughlin, Jimeno, Strauss and McGee, but because they saw this hole from different vantagepoints, they all had slightly different recollections of how it looked and felt.

“Listening to all the rescue workers stories, we got a pretty good idea of it spatially. The problem was that they took shifts and changed positions every twenty minutes, so nobody had a clear picture,” says Roelfs. “Between them all, and talking to Will and John, we pieced together the way they were positioned.”

Roelfs notes that he took his cues in the structure and design of the set from the way McLoughlin and Jimeno were positioned in the collapse. “When John realized the tower was collapsing, he ordered his guys to make a run for the service elevator – he thought that was the strongest spot,” says Roelfs. “He was miraculously correct; it stayed intact. After the tower came down, somehow John ended up lower and Dominick and Will ended up higher. So, we built that: a three-story elevator shaft set on wheels and a track, so that Oliver could position it and the camera as it suited him. The set had two floors, to show Dominick and Will above John. Pieces of debris hung in on a semi-circle track from the ceiling and we could lower or raise them.”

Roelfs’s Ground Zero and hole sets passed the ultimate litmus test: In January, Stone brought John McLoughlin, Will Jimeno, Scott Strauss, Paddy McGee, John Busching, Scott Fox, Tommy Asher, many of the cops and firemen who helped rescue McLoughlin and Jimeno and all of their families to Los Angeles for four to six weeks. They served as technical advisors and, in some cases, recreated what they did on the pile and in the hole, playing themselves.

Roelfs’s sets were so realistic that it gave them pause. Upon arrival to Los Angeles, McLoughlin, Jimeno, Strauss, McGee and Asher came directly to the Ground Zero set, on the first night the crew filmed there. In all, over 50 real-life PAPD, NYPD, and FDNY members who were at Ground Zero came to Los Angeles to appear in the film. In the end, all the prominent police and fireman extras in the film would be played by these real-life heroes.

In addition, they played a valuable role in helping the filmmakers ensure accuracy in the film’s dialogue. If the dialogue sounded sketchy to the men – as in, “New York firemen/policemen/ESU officers would never say that!” – they’d pipe up and script changes quickly resulted.

The sight of the set was particularly disquieting for Strauss, McGee and Asher, who intimately knew and vividly remembered the awful site, in a way that was different from McLoughlin and Jimeno, who mainly recalled coming out of the rubble. Like most of the world, McLoughlin and Jimeno saw Ground Zero on television, albeit months later, in a hospital. The hole set unsettled everyone.

Roelfs’s attention to detail in constructing the set impressed and unsettled McLoughlin and Jimeno, who arrived in Los Angeles on the first night that the crew filmed on the Ground Zero set. “I had no preconceptions about what I would see, but my first impressions of the rubble pile and especially of the hole were a little unnerving,” McLoughlin says. “I didn’t feel comfortable and kind of stayed back. It had the same effect on the firemen and police officers that were there that night. It was good for all of us to be together, with that kind of emotion – a kind of reunion that we never had.”

Revisiting these events became a form of therapy for the real men. McLoughlin had many conversations over the course of production with the firemen and ESU officers who rescued him. They had not seen each other as a group since 9/11 and after filming, they convened at the hotel and talked about the tragic events of that day, something they had never done previously. McLoughlin thinks the re-enactment became cathartic for all of them.

Peña says that acting in the hole presented a unique set of challenges and opportunities as an actor. “With all that twisted metal around us, the dust and debris, there were only so many choices you could make as an actor,” he says. “I tried to paint a picture with the dialogue, to form and have a real sense of Will’s family, and his obvious connection to John. Being in the hole felt real – my body was definitely telling me to get out of there. Obviously, it was not as painful as what Will went through, but it gave me a sense of it.”

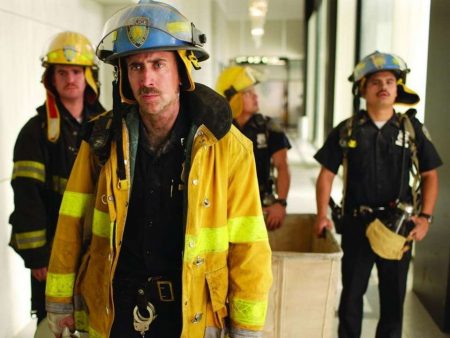

Like every department on the film, Michael Dennison’s costumes had to be 100% accurate. Dennison and his crew did extensive interviews with the actual people involved to ascertain what kind of clothes they would wear. He also worked closely with the Port Authority and a multitude of police and fire departments to get the correct cut and line of the uniforms, which were purchased from the vendors that supply the real uniforms to the Port Authority.

“Doing all the research and finding all the divisions, units, cities, and townships that responded, as well as all the minutia of the uniforms and what exactly was worn on that day, it was an enormously detailed job,” says Dennison. “But, everybody from everywhere responded and helped us. I’m thrilled that there were so many representations in the movie, that we got the chance to honor as many people as possible.”

In creating a color scheme for the film, Dennison, with Roelfs, McGarvey and Stone, worked out a color scheme that would begin very vibrant, but become more muted at the Trade Center itself. “The color scheme was based on concentric circles, with Ground Zero as the center point,” explains Dennison. “Most of the color in the movie happens at the outside perimeter; as we start moving into the city, the color starts to desaturate. We pulled more and more color out of the clothing so that you begin to see the core accent colors start to come forward. By the time we get to Ground Zero, there is almost no hue at all, with blaring pops of the emergency colors. You can see it in the set dressing as well as the costumes.”

For the colors themselves, Dennison looked to the people and departments that the film would honor. “We decided to base the colors of the film on the colors of the Emergency Response Units in New York City, which are blue, yellow, bright orange, white, and green. We also used the silver tape that firemen wear. Sometimes these colors were very prominent, other times subliminal, but they are always somewhere in the movie,” Dennison says.

Dennison adds that the women also have their signature colors – Maria Bello mostly wore blue and Maggie Gyllenhaal donned reddish hues. “We came up with those colors to reflect the women’s personalities,” he says. “Allison is very dynamic and straightforward, so we had her in bolder tones. Donna, on the other hand, is soft-spoken, but John’s rock; she is the glue of her family. In real life, she favors blues and soft pinks and turquoises, so we went with those for her character.”

As in every production, collaboration between departments was critical. This cooperation is exemplified by one scene in particular. In one sequence, Will Jimeno, a devout Catholic on the border of consciousness, is awed by an apparition of Jesus Christ, which he says was crucial in giving him inspiration to survive. To film the event exactly as Jimeno experienced it – and not as an interpretation – required a collaboration between costumes and camera.

“I’d done a shot in a short film that involved this 3M Scotchlite tape, the kind that firemen wear on their uniforms,” says McGarvey. “I had a mad idea to shoot this scene with Jesus through a half-silvered mirror, and this tape would figure into Jesus’ costume. Michael Dennison immediately grasped this notion and designed this extraordinary costume using this material,” McGarvey recalls.

“All emergency uniforms have, in some way, a sort of reflective property to them. I had 3M Scotchlite create that reflective tape in fabric so that I could drape it and I made a robe for Jesus out of that,” says Dennison. “That tape is famous for reflecting 500 times the amount of the light source that hits it. Seamus then took his light and bounced it off this refractive mirror and hit the costume dead on. When the beam of light hit the costume, it completely exploded in light. We got a special effect without it really being a special effect.”

World Trade Center (2006)

Directed by: Oliver Stone

Starring: Nicolas Cage, Michael Peña, Maria Bello, Jay Hernandez, Maggie Gyllenhaal, Alexa Gerasimovich, Morgan Flynn, Armando Riesco, William Jimeno, Martin Pfefferkorn

Screenplay by: Andrea Berloff

Production Design by: Jan Roelfs

Cinematography by: Seamus McGarvey

Film Editing by: David Brenner, Julie Monroe

Costume Design by: Michael Dennison

Set Decoration by: Beth A. Rubino

Art Direction by: Richard L. Johnson

Music by: Craig Armstrong

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for intense and emotional content, some disturbing images and language.

Distributed by: Paramount Pictures

Release Date: August 9, 2006

Views: 142