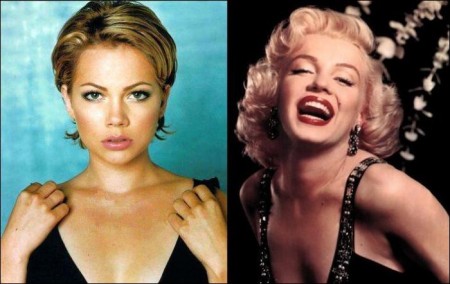

Michelle Williams discusses her months with Marilyn. Pixie powerhouse Michelle Williams, 31, is Oscar-nomination bound for her drop-dead Marilyn Monroe in the whimsical memory-piece “My Week with Marilyn.” The two-time Oscar nominee (“Blue Valentine,” “Brokeback Mountain”) talked to Yahoo! about that famous wiggle — “It was like she was doing a figure eight in a vat of honey” — while making tea. Then she was off to the set of Sam Raimi’s “Oz: The Great and Powerful,” where she’s playing yet another blonde with pop culture baggage: Glinda the Good Witch.

How did you transform into Marilyn?

Michelle Williams: It was a long process. I started my prep maybe ten months in advance of shooting, I started watching her movies over and over again, listening to her voice on headphones, or playing it in the car when I drove carpool. I started to surround myself with her before I even tried to do any thing close to mimicry, before I attempted a walk or a talk. It takes a long time for me to break some thing like that down, to see patterns.

What was the first patterns you discovered?

Marilyn moved in a series of fluid poses. She got her start in modeling. In her films, she’s always referencing her own body, she’s guiding your eyes where to look, she puts her hand to her face, or her hip, or traces up the side of her body. She’s subconsciously guiding your eyes. The way that she moved is like she’s posing, but it’s fluid.

What were her signature poses?

She had a few signature poses: the hand up in between her breasts and her head back in laughter. It looks like she’s just sort of discovered some thing for the first time.

Was it spontaneous?

What’s so impressive about her is that it was a craft. She studied her body, her face. By all accounts, at times she was an ordinary looking girl but she was able to rearrange herself, poses, gestures, persona — but she did it so seamlessly that you couldn’t really guess it was a performance.

How close do you feel you came to solving the riddle that was Marilyn?

Like any thing in life, one thing becomes clear and then you have a whole other thing to deal with. You can never really rest. You’re constantly figuring stuff out but then the next hurdle or challenge comes along. I certainly know more about her than when I started but it could be a lifelong process.

You’ve said that she seemed to lack a strong core…

MW: I thought that she didn’t have a center, a place inside to return to — in a way there was no going home. Every thing had to come from the outside for her: husbands, friends, confidantes, and teachers. She was fed on other people’s belief in her, wisdom, support. There were very few opportunities where she could go inside and find a calm place to rest.

While she may have lacked a strong center of gravity, she had incandescence to burn, right?

It’s superhuman, not entirely natural. Some of that was a learned behavior that got her what she needed, a survival trick. She grew up passed around from distant family member to distantly family member to foster parent to orphanage. She got married at 15 to escape the system. No father would claim her. Her mother couldn’t take care of her. Her incandescence was a way to get love. It was like going to the pound: the dog that licks you, that loves you the most because they want to get out.

With all this electricity, she must have needed to recharge, right?

The photographer Richard Avedon would say she would be ablaze when they were taking pictures, but then would collapse after with a drawn look and wouldn’t want to be photographed any more. It took a lot of energy to be what other people wanted her to be. She was also just touched. She got an extra gift in that area, a freakish amazing talent.

Is it true that you practiced being Marilyn in private moments?

I would. Like when the Fedex lady would come to our house, I would try little things. When the Census Bureau came, I tried on my early Marilyn, just to try to get comfortable and take a risk in front of a stranger. It was a voice change, a posture, this way she had of looking like she was almost a newborn baby, like her body had just woken up.

How much control did Marilyn have over her career and image?

She was living and working in the time of the studio system when you were on salary all year round. The decisions were made by someone else, usually a man, and for a while that was really all that she wanted, constant employment working her way up and developing and playing this character she’d developed: Marilyn Monroe. And then there came a moment where she realized she had built herself a prison and she didn’t just want to play this sex object. She was thirty-years-old and she formed her production company with her friend Milton Green.

Played by Dominic Cooper in the movie, which centers on the English production of “The Prince and the Showgirl,” directed by and co-starring Laurence Olivier…

Marilyn was attempting to break free and become an independent artist instead of a studio system pawn. Strangely the role she picked to break free was that of a daffy showgirl. The character she created — Marilyn Monroe — was so popular that when she talked about her scholastic aspiration or her love of books, that beloved image collided with being a real brainiac.

Was she a brainiac?

Her personal letters, poetry, drawings, recipes, even things thank you notes: that side of her comes thru in her every flick of her pen. She was a real honest-to-goodness artist with a sharp functioning witty mind.

Has her decision to change her course at 30 had an impact on your life-work decisions?

The biggest lesson of my 30’s, that I’m trying to learn is that “no” is not a bad word. “No” will not shut out the world. “No” is not a deafening roar to other people; an adjustment happens, not the end of every thing. “No” is a very powerful word. I’m letting go of the compulsion to be a good girl. Instead, I just have to be me and trust that that person is a good girl and doesn’t have to please to make other people happy. It’s what I say to my daughter Matilda [Ledger, 6] all the time: ‘There’s no such thing as perfect, there’s only real.’

Views: 217