Prelude to a Kiss movie synopsis. Despite her pessimistic outlook on life, Rita Boyle, a liberal, free-spirited, aspiring graphic designer working part-time as a bartender, falls in love with Peter Hoskins, the conservative employee of a Chicago publishing house. At their wedding, they are approached by Julius, a lonely elderly man who requests permission to kiss Rita.

When he does, their spirits somehow switch places, leaving Peter with the aged man’s soul residing in his newlywed bride, and her soul in his cancer-riddled body. Peter eventually sees beyond the physical and embraces the beautiful soul he loves. Only after convincing both Rita and Julius why they switched (she was afraid of life and wanted to be an old person who had already gone through the fears life would throw at her, he was afraid of dying and wanted to be young again), and how they did not have these fears anymore, are they able to return to their rightful bodies.

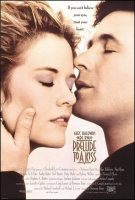

Prelude to a Kiss is a 1992 American romantic fantasy film directed by Norman René and starring Alec Baldwin, Meg Ryan, and Sydney Walker. It is based on the 1988 play of the same title. The film grossed $20,006,730 in the US and $2,690,961 internationally for a total worldwide box office of $22,697,691.

The film’s title is derived from the Duke Ellington / Irving Gordon/Irving Mills tune of the same name, which is heard performed by Deborah Harry during the opening credits. The soundtrack also includes the Cole Porter song “Every Time We Say Goodbye” performed by Annie Lennox, “The More I See You” and “I Had the Craziest Dream” by Harry Warren and Mack Gordon, “A Certain Smile” by Sammy Fain and Paul Francis Webster, “The Very Thought of You” by Ray Noble, “Sweet Jane” by the Cowboy Junkies, and “Someone Like You” by Van Morrison. In the beginning, Rita dances to the song “I Touch Myself” by Divinyls.

Film Review for Prelude to a Kiss

“Prelude to a Kiss,” adapted by Craig Lucas from his successful play and directed by Norman Rene, who directed the stage production, is a contemporary romantic comedy with the heart of a very dark fable. It’s “Beauty and the Beast” with a wicked twist, in which Beauty becomes a beast and it’s the prince’s love, not Beauty’s, that is put to the test.

Peter Hoskins (Alec Baldwin) works in a Chicago publishing house. Rita Boyle (Meg Ryan) is an aspiring graphics designer who makes her living as a bartender. A product of a broken home, he is self-aware, solid, comparatively conservative. Rita, whose parents are loving, eccentric and protective, is a determinedly free spirit. They meet at a party and, after a brief idyllic affair, decide to marry.

Up to this point, Peter and Rita are exemplars of the contented American middle class. Then something dumbfounding happens. A strange old man (Sydney Walker) appears at their wedding reception, held outdoors overlooking Lake Michigan at her parents’ house in Lake Forest. Nobody knows the old man, who seems to be a bit addled.

Yet it’s a glorious day, and Rita is inexplicably as drawn to the old man as he is drawn to her. He asks to kiss the bride. She laughs and says she would be pleased.

In the moment it takes for a cloud to pass in front of the sun, Rita and the old man exchange souls. The bewildered bride finds herself inhabiting the body of an old man who is dying of lung cancer. At the same time, the old man enthusiastically accepts his second chance, even if it means living a life he has never dreamed of.

The novelist Thorne Smith once used such gender switches for gently ribald comic effect, especially in “Turnabout.” Mr. Lucas is interested in more serious things, though he doesn’t entirely dismiss the humor. The Jamaican honeymoon turns out to be a disaster for Peter. His beloved Rita, a self-described former socialist, becomes a typically acquisitive American tourist. Further, she would rather chat up boring vacationers than have sex. Very quickly Peter suspects that Rita is not herself and that, in fact, she’s not Rita at all.

If I’ve taken rather a lot of space to set up the central situation, it’s because the film does too. The sad news about this movie adaptation is that it functions as a cruel critique of the problems that, for whatever reason, did not seem important in the stage production. This “Prelude to a Kiss” is not only without charm and wit, but it’s also clumsily set forth: many people seeing it may wonder what, in heaven’s name, is going on.

The center of “Prelude to a Kiss” is a single extraordinary scene. Late one night after the terrible honeymoon, after Rita has run home to her parents, Peter wanders into the Chicago bar where she used to work. Fiddling with his drink, feeling bereft, he looks up to see a strangely familiar old man sitting on the other side of the bar. Behind the old man’s ravaged, forlorn and frightened face, Peter suddenly recognizes the vital young woman he said he would love and cherish until the end of time.

It’s a coup de theatre of exalting order, a scene of almost indescribable sweetness and humor followed by desolation. Peter and the transmigrated Rita are initially joyous at rediscovering each other, but then they consider their options, which are few. They can’t even hold hands in public.

As staged in the theater by Mr. Rene, this scene was so spellbinding that it had the effect of enriching all that came before and all that was to come after. It was the heart of the matter the play was about: a love so rare and profound that it transcends physical decay and imminent loss. Not incidentally, it was also a poignant reflection on the trials of love in the era of AIDS.

Mr. Rene, in his capacity as film director, somehow flubs this scene so completely that the movie never gathers the emotional momentum that would make everything else work. Its failure is more easily reported than blame can be attributed.

Unlike the play, which takes place within a unit set and can move with the speed of light, the opened-up film lumbers like someone on crutches.Against the literal surroundings of Chicago, the North Shore and Jamaica, Peter, Rita and the old man become perfunctory characters, interesting only for the bizarre situation in which they are caught. They lack any convincing particularity or idiosyncrasy.

The same dialogue that served well enough on the stage now sounds arch and coy or metaphysically flat. The explanation for the turnabout has its roots in early Walt Disney, specifically in a song from “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.” It seems that at the wedding reception the old man so envied Rita’s happiness, and she was so moved by his loneliness, that they became the unknowing instruments of the switch. “All you have to do is want it bad enough,” says the old man, paraphrasing the Disney dictum that “wishing will make it so.”

The performances are colorless, though Mr. Baldwin’s hair looks so unnaturally black that it seems that it’s going to be a plot point, which it isn’t. The camera doesn’t reveal characters. The close-ups corner the actors to expose banalities. Mr. Baldwin, who played Peter on the stage in New York, can be a terrifically tough and funny actor but seems drab in the movie. The harder Ms. Ryan works to be engaging, the less effective the results. Mr. Walker, who played the old man in the play’s West Coast production, is simply sorrowful.

Kathy Bates, Ned Beatty and Patty Duke give some substance to the smaller roles. It can be assumed that Mr. Rene and Mr. Lucas, whose first movie collaboration was “Longtime Companion,” were allowed a free hand in the production of “Prelude to a Kiss.” The film becomes an unfortunate argument against allowing a play’s true auteurs to wish on stars.

Prelude to a Kiss (1992)

Directed by: Norman René

Starring: Alec Baldwin, Meg Ryan, Kathy Bates, Ned Beatty, Patty Duke, Sydney Walker, Stanley Tucci, Debra Monk, Annie Golden, Frank Carillo, Sally Murphy, Lucina Paquet, Jane Alderman

Screenplay by: Craig Lucas

Production Design by: Andrew Jackness

Cinematography by: Stefan Czapsky

Film Editing by: Stephen A. Rotter

Costume Design by: Walker Hicklin

Set Decoration by: Jennifer Chang Binns, Cindy Carr

Art Direction by: W. Steven Graham

Music by: Howard Shore

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for language (sex related dialogue.

Distributed by: 20th Century Fox

Release Date: July 10, 1992

Views: 178