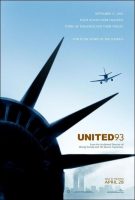

Taglines: The war on terror begins with 40 ordinary people.

United 93 movie storyline. There are lots of ways to find meaning in the events of 9/11. Television can convey events as they happen. A reporter can write history’s rough first draft. Historians can widen the time frame and give us context…Filmmakers have a part to play, too, and I believe that sometimes, if you look clearly and unflinchingly at a single event, you can find in its shape something much larger than the event itself-the DNA of our times…Hence a film about United 93. – Paul Greengrass

Filmmaker Paul Greengrass-the compassionate and socially aware writer/director behind films that study the impact of terrorism in Northern Ireland in Bloody Sunday and Omagh, racial violence in The Murder of Stephen Lawrence and one soldier’s abandonment in Resurrected-now focuses his cameras on the day that changed the world forever.

In United 93, Greengrass creates a gripping, provocative drama that tells the story of the passengers, crew and the flight controllers who watched in dawning horror as United Airlines Flight 93 became the fourth hijacked plane on the day of the worst terrorist attacks on American soil: September 11, 2001.

The filmmaker explores the events of this day by telling the story of a single flight and the ordinary, random sampling of flight crew, businessmen, wives, grandparents, students and others bound for San Francisco aboard a Boeing 757. In the course of the just over 90 minutes that the plane was aloft, the world below entered a new and violent age-viewed through a fog that slowly dissipated to reveal that America herself was under attack.

Faced with the daunting task of re-creating the events that took place onboard the doomed plane and down below, Greengrass and his researchers called upon a myriad of sources, conducting countless hours of face-to-face interviews with the families of the 40 passengers and crew, members of the 9/11 commission, flight controllers and other military and civilian personnel who took part in the events of the day. These interviews were distilled and, along with details from flight recordings, public record and historical fact, became the basis for the film. It was then played out by an ensemble of talented, yet largely unknown actors-democratically presented as random people sharing a flight-whose fact-grounded and acutely directed improvisations provided the highly charged human drama captured by Greengrass’ cameras.

The result is a trenchant study-chronicled and filmed in real time-of the incendiary collision of modern day and old world…and the courage that was born from such a crucible. Greengrass asserts, “One of the reasons why United 93 exerts such a powerful hold on our imaginations is precisely because we don’t know exactly what happened. Who among us doesn’t think about that day and wonder how it must have been and how we might have reacted?”

Painstakingly researched with the support of the families of the passengers and crew who lost their lives, United 93 paints an unforgettable and inspiring portrait of everyday people confronted with an unthinkable situation…who unwittingly become the first denizens in the new era of global terrorism that began that September morning.

In choosing the cast, the filmmakers sought to bring together an ensemble comprised of gifted actors (and, in some cases, real-life flight crew members, controllers and other personnel) who came armed with the talents and skills necessary to create vivid and real snapshots of the actual men and women onboard and involved with United Airlines Flight 93. All approached the subject matter with the utmost sensitivity, keeping two goals at the forefront of their minds-to dignify the memory of those they were portraying and to arrive at, as Greengrass puts it, “a believable truth” of what happened during the 91-minute flight.

About the Production

Paul Greengrass has spent the larger part of his career crafting socially-aware, humane films about some of the thorniest issues of our modern day-the flashpoint at which politics turns to violence, beliefs slip into zealotry-in addition to helming an international blockbuster thriller, 2004’s The Bourne Supremacy.

He is perhaps best remembered for his critically acclaimed, cinéma vérité exploration of the 1972 incident in Londonderry, Northern Ireland, when 13 unarmed civil rights demonstrators were shot by British soldiers-2002’s visceral drama, Bloody Sunday. In his review of the film, Los Angeles Times’ critic Kenneth Turan called it, “A compelling, gut-clutching piece of advocacy cinema that carries you along in a torrent of emotion as it explores the awful complications of one terrifying day. Bloody Sunday shows the power of real events dramatically conveyed. Made by writer-director Paul Greengrass out of a sense of communal outrage that has not gone away, this film never wavers, never loses its focus or its conviction. Bloody Sunday does the spirit of that awful day full and unforgettable justice.”

Greengrass is, therefore, uniquely qualified to tackle a film that concerns the events that occurred on September 11, 2001, possessing both sensitivity to the subject matter (and its larger themes) and the cinematic talent to handle such a project (with its multiple story threads and constantly shifting viewpoint). Since that autumn day nearly five years ago, the filmmaker has been intent upon telling a story of the epochal events of 9/11, with the question being, “At what point is it okay to put such a painful time on the screen?”

According to Greengrass-informed with interviews from more than 100 family members and friends of the 40 fallen passengers and crew-the right time is when the families say, “Yes.”

Greengrass says, “There are all sorts of films made. We make films to divert us, to entertain us and to make us laugh-to take us to fantasy worlds and to make us understand love. But also, there’s a place for films that explore the way the world is. And Hollywood has a long and honorable track record of making those types of films as well.”

What Greengrass believes is that in examining the story of United 93, we see, in shocking microcosm and within the span of a mere half-hour, the challenges that now face our world as a whole. He continues, “Forty ordinary people had 30 minutes to confront the reality of the way that we’re living now, decide on the best course of action and act. They were the first people to inhabit the post 9/11 world-at a time when the rest of us were watching television dumbstruck, unable to understand what was going on. At that moment, those people onboard that airplane knew very well-they could see exactly what they were dealing with-and were faced with a dreadful choice. Do we sit here and do nothing and hope for the best, hope it turns out all right? Or do we do something about it? And if so, what can we do?

“It seems to me that those are the two choices that face us today and have faced us ever since that day. When you look at what happened on that airplane, you can see that there was a debate, an anguished debate in the most terrible of circumstances. That group of people weighed those choices, made a decision and acted upon it. And I think that if we look at what happened, we find a story of immense courage and fortitude-those people were very, very brave. But we also find wisdom.”

With regard to the timing of a motion picture about 9/11, Allison Vadhan, daughter of UA 93 passenger Kristin White Gould, offers, “It’s never going to be over for us families who’ve lost loved ones. It’s never going to be over for the country, anyone who witnessed it on TV. It’s always going to be touchy, awkward…and something that a part of us don’t want to see again. But I feel the more films, the better. We can’t forget. We have to remember what happened, why it happened. And we can’t fool ourselves into thinking that it won’t happen again if we forget about it.”

Sandy Felt, who lost husband Edward P. Felt on the flight, explains, “There are lots of things in life that are difficult to do, and we do them because they’re the right thing to do. This is one of those situations-I got involved in this because it was the right thing to do. I can’t deny its existence. I don’t know that it’s going to be any different for me a year from now, two years from now-it’s happened, we deal with it. So I’d rather give you the story, and I’d rather remember the man that he was and be able to keep him alive for myself that way.”

Kenny Nacke, brother of passenger Louis J. Nacke, II, shares, “I’m glad it’s being made because it’s the fifth year anniversary of it-and I would hate to see those 40 individuals forgotten. What if roles were reversed? I’ve done that, I’ve said, `Well, what if I was on Flight 93, and my brother was here today?’ And that’s why I’m involved. I think he would have the loudest voice. He would say, These individuals need to be honored, cherished and remembered.’ And I’m going do my part to see that they are, and they’re given the credit that they’re due-not only for who they were, but what they did that day.”

Genesis of the Film

Well before his contact with the families had bolstered Greengrass’ intention to make a 9/11 film, the writer/director had been vigilantly following the media’s coverage of the day and its aftermath. After the completion of The Bourne Supremacy and the interruption of a subsequent studio project, the filmmaker’s thoughts about making the film returned, “But I wasn’t sure it was the right time.”

He discussed his idea with producer Lloyd Levin: to use United 93 as a focal point, a prism through which to view the events of the day, to give the audience “an extraordinary way into 9/11.” Greengrass then sat down and, drawing on his previous work and research, composed a document that included his feelings and ideas about the project, which eventually became a 21-page treatment. Completed, it contained his reasons for making the film, as well as a time-coded, scene-by-scene plot, telling the general story of the morning as viewed by those in the flight towers and centers on the ground and those aboard the plane itself. This, in turn, was used to pitch the project; eventually, production and distribution deals were secured in the summer of 2005.

Greengrass’ aim to keep the story among the flight controllers and the flight’s passengers and crew was intentional. Quoting from the treatment, he says, “It’s not a film with neat character arcs. What it does do is pick up 44 individuals as they congregate at the airport for a plane journey, follow them as they enter the plane, and take their 90-minute journey in real time, cutting away only to the various air traffic control centers that follow their progress, on whose screens the entire horror of the full 9/11 operation is played out.”

In August, Greengrass tapped associate Kate Solomon to act as researcher and family liaison. Solomon began by sending a letter to all of the families of United 93’s passengers and crew. In the letter, Greengrass’ goals for the project were discussed, and he asked for their cooperation in helping to establish profiles of all of those onboard. Ultimately, nearly all of the families participated in the process. What followed in September and October was seven weeks of face-to-face interviews with the families and friends-more than 100 were conducted in all.

Solomon provides, “They wished to be involved, to honor and remember their loved ones. It’s still a painful subject, but many felt that their involvement would help us get it right.”

The families were also kept involved all through production of United 93. They were notified once casting had been completed, and were sent a full cast list and a cast picture of the actors who would portray their family members-some of the actors personally met with the families, while others got in touch on the phone. Solomon also sent out bi-weekly newsletters, which kept them informed of the production’s progress and brought them inside the filming process with articles about Greengrass’ methods of filming and things like set construction, sound recording and other aspects of moviemaking. The director also recorded a video message for the families that was viewable in a privately accessible area of the web site. The result was an open channel of communication between filmmakers and families, which not only kept all mindful of the film’s goals, but also allowed for an ongoing exchange of information. (“Some of the families have taken to calling it `our film,’” Solomon adds.)

To cover the ground personnel who paid witness to the unfolding tragedy that September day, Greengrass enlisted writer and former 60 Minutes II producer Michael Bronner to conduct a second series of interviews-this time with a wide-ranging group of civilian and military personnel. As the big picture of the day only began to come clear once geographically dispersed puzzle pieces were assembled, Greengrass knew his narrative would include sequences in several key sites: the control tower at Newark International Airport (where UA Flight 93 originated and which, because of its location, provides a bird’s-eye-view of Manhattan); Control Centers in Boston (where the hijacked AA Flights 11 and 175 originated) and New York; the Federal Aviation Administration’s operations command center in Herndon, Virginia (under the command of national operations manager Ben Sliney, experiencing his first day in that position on 9/11/01); and the military’s operations center at the Northeast Air Defense Sector (NEADS) in upstate New York. Bronner’s detailed recounting of the events that morning would play a major part in the construction of Greengrass’ script.

Additionally, Bronner researched other factual information on everything from the hijackers to the other planes (commercial, military and private) in the air that morning. Valuable information was also gained from the 9/11 Commission Report; members of that Commission advised on the film prior to start of principal photography and were present on the set during filming.

Greengrass explains, “What we did on this film was to gather together an extraordinary array of people wanting to get this film right-aircrew from United Airlines; pilots; the families of the people who were onboard, who gave us their sense of what their family member might have done given the type of person he or she was in any given situation; controllers and members of the military; the 9/11 Commission. We had a lot of expertise that, in the end, allows you to get a good sense of the general shape of events.”

Research and Fact Gathering

The filmmakers’ decision to shoot at Pinewood was carefully considered. Greengrass’ film would be the product of some improvisation, all based on the known facts, and it was felt that in order for the cast to arrive at their own truths about their characters and the events on the plane, there would need to be a removal from the culture where the impact of 9/11 is still keenly and painfully felt-much as a jury in deliberation is separated from the media and immediate influences of the outside world. During the intense, pre-shoot rehearsal process, as well as during principal photography, a majority of the actors stayed in a hotel near the studio (a few, who were U.K.-based, did return to their homes).

Once they had been signed to their parts, each actor was given a dossier (the product of the researchers and the family input) on the person they would be portraying. These files contained photos, information from the family (What kind of person was he/she?) and practical facts (How did this person get to the airport? What clothing was he/she wearing?). Some of the actors’ research processes included their own personal outreach to the family, while some preferred to develop the character simply with the research provided.

There was an acknowledgement-from the actors and the families-of the difficulty of re-creating a real person who, in the final moments of life, had been subjected to an unthinkable ordeal. Both groups were respectful of the burdens and responsibilities of the other and only interacted if the willingness to communicate was shared by all.

Lorna Dallas, cast as passenger Linda Gronlund, exchanged several phone calls with Linda’s sister, Elsa, and later met with her and Gronlund’s mother, who closed their meeting with a toast to her “new daughter.” Dallas says, after given permission to make the call to Elsa, “I felt at that point that I was talking to my own sister. She made me feel very comfortable. We laughed and cried on the phone-she wanted to know about me, and I told her a few things, told her about my background. And then, it started coming out from her, about Linda. And it was just spilling out-the time on the phone didn’t matter. The minutes just flew by. I had several phone calls with Elsa, and each time, new things came up.”

A trusting bond built, Elsa later shared her sister’s last call with Dallas: “When I heard it, it was rather harrowing and rather humbling to know that someone who knew that the end was very near could have such forethought, such strength to say what she did. She told Elsa exactly where to go for her will. And she ended that phone call with `I love you.’ It took great guts to say what she did on that phone. And it took great guts for Elsa to play it for me…and it will haunt me for the rest of my life. But I will also treasure the thought, and be grateful of the strength of that woman that was shared with me.”

Peter Hermann, signed to play passenger Jeremy Glick, comments, “This is incredibly tender territory that’s been entrusted to us. I mean, it’s an incredible act of trust, as a family member who lost someone on United 93, to give this over, to say, `Yes, you can portray my husband.’ That’s a huge thing. And I think it really helped to be isolated as a cast, that we didn’t disperse at night…and I don’t know what it would have been like to make this movie in the States.”

For Cheyenne Jackson, portraying passenger Mark Bingham brought great responsibility and challenges. He explains, “Early on, they gave us the option to contact family members, and I was really torn about that decision. On one hand, it was a great opportunity to talk to the people that knew these people better than anybody. And on the other hand, it seemed rather daunting. I was pretty trepidatious. But, I did decide to reach out via e-mail to Mark’s mom, and she was lovely. And it was just what I needed. It was supportive, and it was open-she’s a no-nonsense kind of gal, and I really appreciated that. Also I talked to a former partner of his, and also his dad. The whole idea of trying to capture somebody’s spirit, somebody’s essence, though, has been overwhelming.”

Of the phone calls those on United 93 made-like the one from Linda Gronlund to her sister (scripts for which were provided to the actors for use during filming)-Christian Clemenson (who plays passenger Thomas E. Burnett, Jr.) comments, “I’ve read the transcripts or what people recollect of all the phone calls and what strikes me about all of them is how calm these people were. That is astounding to me. Tolstoy wrote that the aim of art is to state the question clearly-it’s not to provide answers. And I think that’s what Paul is doing with this movie.”

The practical research by both Solomon and Bronner also played a part in the costuming of the film, with history helping to determine what the flight crews on United Airlines planes wore in 2001. The type of person each passenger was (again determined from information provided by the family members) was factored into clothing choices for their characters. And as with the outfitting of the plane, reality was the overriding concern for determining the final clothing looks for all.

Once assembled at Pinewood, the cast who comprised United 93’s passengers and crew began their arduous journey together by embarking upon an intensive, two-week rehearsal process. Having digested the background research on their characters, they were now to become those characters involved in a harrowing situation. Much like a stage play (only without a majority of dialogue scripted), the actors would board the plane-the reconstructed, re-dressed Boeing 757-and sit in their assigned seats.

The planes’ doors would be shut and those aboard would re-enact the 91-minute flight in real time…from take off to the descent over Pennsylvania. These improvisations were executed within certain parameters, such as the times of known events (e.g., the mundane first 46 minutes of the flight, the takeover of the plane, air-to-ground communications) and the “makeup” of their characters (e.g., leader or follower). Times were called out during improv and filming, to give the actors a framework on which to shape their communal drama. Executed repeatedly, with various sequences of the improv revisited over and over during the course of the two weeks, Greengrass’ goal of the “plausible truth” began to emerge.

Greengrass explains, “We improvised based on the known events. And all the time we were engaged in a debate about how believable it was. How might a group of young men have reacted in this situation? How might more elderly people on that airplane have reacted? How might the flight attendants have reacted? You know, those are the questions that we discussed, and tried to arrive at a workable solution in an improvisatory style.”

Olivia Thirlby (playing passenger Nicole Carol Miller) reasons, “Working with improvisation has been appropriate for this project and for this subject matter. We just have no way of knowing the events that happened on the plane. There would be no way to script it in a way that would end up seeming realistic. This is such touchy subject matter-and I think that if it’s not going to be truthful and it’s not going to seem real, then there’s just no point in doing it.”

Susan Blommaert (playing passenger Jane Folger) adds, “I feel like Paul is anti-sensationalist and an anti-sentimentalist. It was always about trying to create, as honestly as we possibly can, what could have happened on that plane. There was no pretense to make it anything other than that. I think that has really been inspirational to all of us, and I think the only way that you can feel justified in doing this movie.”

Marceline Hugot (playing passenger Georgine Rose Corrigan) offers, “Paul basically wanted us to respect profoundly who we were representing. Learn as much or as little as was available about the person and embody that, making decisions within that framework. `It became a marriage between an actor and a person who lived, breathed, had a full life and tragically ended up in a horrible, horrible situation. So it was about trying to re-create that for myself, and then, way beyond…for the family. It’s surprising how simple, not simplistic, a process it really is. And to have a director encourage that clarity and simpleness of heart is rare…and I’m hoping the film’s as powerful to see as it has been to do.”

Greengrass sought to keep the rehearsal process truthful. Since the onboard conflict was literally a deadly contest of “us against them,” the director kept the four U.K.-based actors who were cast as the plane’s young hijackers separate from the 40 passengers and crew-and introduced them as late in the game as he could. These actors had also been provided with factual information about their characters, including the written instructions for their mission from the leader of the 9/11 plot, Mohamed Atta. Additionally, they were given intense, accelerated physical training from martial arts experts.

All through pre-production and rehearsal, Greengrass had been developing a “shooting script” which listed scenes and action. Also, verified dialogue of ground and flight personnel was included. After the culmination of the rehearsal process, the scenes aboard the plane were fleshed out with a great deal of description of the action, but only a few bits of key dialogue-the remainder would be provided during the filmed sequences out of the reality created during on-camera improvisation.

Principal Photography

Principal photography of United 93 began in mid-November, on the sets that the actors had come to know very well during the time spent in rehearsal. The first scenes shot involved the entire plane. As previously, the plane was boarded with the doors sealed-and filmed takes varied in duration, from anywhere between a few to as many as 40 minutes. Filming was executed by two camera operators who, along with sound men and assistant director, would run up and down the length of the set at the direction of Greengrass, communicating with them from outside the plane through microphones and earpieces. (The final task of making a seamless film from these different segments would fall to Greengrass and his team of three editors.)

Next, scenes were completed in the separate cabins-first economy, then first-class. The harrowing last minutes fighting for control of the plane were shot separately, with the cockpit fixed to a computer-controlled hydraulic gimbal, designed in cooperation with the special effects department, which pitched and rolled in simulation of a plane spiraling out of control.

Even with all of the rehearsal, scenarios and objectives still continued to be refined. Peter Hermann remembers a take at the end of a full day: “By the time that we’d got to shooting the final scenes in that contained space, we were incredibly tired and there was a lot of accumulated adrenaline. I think that, in a sense, it’s those moments that become a real luxury, because the objective is so clear: get in that door, and get anybody who’s in the way out of the way. It just becomes so basic and so clear.”

The first-class section was later fitted into a rotating gimbal, which could turn the cabin 180 degrees during the filming of the final scenes, as the plane is making its last (and very steep) dive. To lessen the chances of injury, the seat frames, backs and armrests were refitted with soft foam in place of the hard plastic and metal. Stunt performers were originally intended to stand in for the cast in these scenes, but the actors wished to execute the work themselves. With extra padding built into their costumes, they successfully completed their own stunts.

Greengrass observes, “That final image haunts me-a physical struggle for the controls of a gasoline-fueled 21st-century flying machine between a band of suicidal religious fanatics and a group of innocents drawn at random from amongst us all…I think of it often. It’s really, in a way, the struggle for our world today.”

On the filming of the final sequences between the hijackers and the hijacked, Kate Jennings Grant (playing passenger Lauren Catuzzi Grandcolas) observes, “It was astounding to me that as actors (and we know what’s going to happen), there was still something in us that I think was also in those passengers: the undeniably human-and I’d like to think American-urge to cling to hope. You cling and you fight because life is extraordinary. One life is extraordinary and worth it. In those moments where I started to collapse from exhaustion crawling up that aisle, I would think of Lauren, and I would think of my family and all those I would be flying home to…and I kept going and going and going.”

Filming on the sets of the control centers and towers was given the same attention to improvisational truth and detail-all executed within the parameters of actual timing and known fact. Whether Greengrass’ cameras were focused on one screen, one individual or the entire facility, all actors were engaged, performing and reacting in every take-even if what they did was clearly out of frame.

Sometimes, the convergence of the filmic world and the real world proved to be a near overwhelming experience for those involved. As a real-life flight attendant for United, Trish Gates had been pulled from her original assignment to work a Newark/Los Angeles flight two days before September 11. The day prior, she had worked a trip up to Portland, where she was grounded for five days following. She remembered a poster that showed the faces of the crew members killed on September 11-in particular, the face of Sandra Bradshaw, the woman she was cast to portray. Gates tells, “The first two weeks of rehearsal, I was busy trying to make sure that everything looked real and that all of the attendants were doing the right thing. Then, I felt the responsibility that she was an actual person the day we started shooting-it hit me. I looked again at all the information and the pictures, and I felt this enormous responsibility to do right by her…to do the best job that I could. Before every take, I would look at this little family portrait, and think about her children-the youngest one doesn’t have a memory of her, and that just broke my heart.”

It is that very convergence of realities-resulting in a communally discovered truth-that compels Paul Greengrass to make films like United 93. He closes, “I hope that people see that this film has been made in a serious way by serious people trying to do a difficult thing, which is to explore a very painful event-and that it’s been done in a dignified way and that what we present is a believable truth. If we do that, well, I will feel that we’ve done as best we can. September 11, no matter where you are on the political spectrum, changed our world. It forced us to confront the way our world is going, and it presented us with some hard choices. That’s what a film needs to do, to help us understand some of those things…but also, of course, to take us to the heart of the human stories of those involved.”

United 93 (2006)

Directed by: Paul Greengrass

Starring: J. J. Johnson, Gary Commock, Polly Adams, Opal Alladin, Nancy McDoniel, Trish Gates, Khalid Abdalla, Susan Blommaert, Liza Colón-Zayas, Lorna Dallas, Starla Benford

Screenplay by: Paul Greengrass

Production Design by: Dominic Watkins

Cinematography by; Barry Ackroyd

Film Editing by; Clare Douglas, Richard Pearson, Christopher Rouse

Costume Design by: Dinah Collin

Set Decoration by: Michael Standish

Art Direction by: Romek Delmata, Joanna Foley, Alan Gilmore

Music by: John Powell

MPAA Rating: R for some intense sequences of terror and violence.

Distributed by: Universal Pictures

Release Date: April 28, 2006

Views: 80