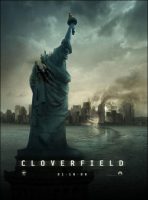

Taglines: Some thing has found us.

Cloverfield movie storyline. On the eve of his departure for Japan, Rob (Michael Stahl-David) sees his going-away party as an opportunity to confess unresolved feelings and tie up loose ends. His agenda takes an unexpected turn when a jolt shakes the revelers. The crowd quiets down to watch news reports of an earthquake, then rushes to the roof to assess the damage. A fireball explodes on the distant horizon. A power failure follows. Confusion gives way to panic as the partygoers stumble through the blackout. Amid the human screams and one inhuman roar, Rob and his friends must traverse a landscape that has changed, overtaken by something otherworldly, terrifying, monstrous…

Cloverfield is a 2008 American found footage monster horror film directed by Matt Reeves, produced by J. J. Abrams and Bryan Burk, and written by Drew Goddard. The film, which is presented as found footage shot with a home camcorder, follows six young New York City residents fleeing from a gigantic monster and various other smaller creatures that attack the city while they are having a farewell party.

Cloverfield opened in 3,411 theaters on January 18, 2008, and grossed a total of $16,930,000 on its opening day in the United States and Canada. It made $40.1 million on its opening weekend, which at the time was the most successful January release (record then taken by Ride Along in 2014 with a weekend gross of $41.5 million).[60] Worldwide, it has grossed $170,602,318, making it the first movie in 2008 to gross over $100 million.

Before the film’s release, Paramount carried out a viral marketing campaign to promote the film which included viral tie-ins similar to Lost Experience. Filmmakers decided to create a teaser trailer that would be a surprise in the light of commonplace media saturation, which they put together during the preparation stage of the production process. The teaser was then used as a basis for the film itself. Paramount Pictures encouraged the teaser to be released without a title attached, and the Motion Picture Association of America approved the move. As Transformers showed high tracking numbers before its release in July 2007, the studio attached the teaser trailer for Cloverfield that showed the release date of January 18, 2008, but not the title.

Making “Cloverfield”

“We live in a time of great fear. Having a movie that is about something as outlandish as a massive creature attacking your city allows people to process and experience that fear in a way that is incredibly entertaining and incredibly safe. I want to have that experience myself — to go to a movie that’s about something larger-than-life and hyper-real, and `Cloverfield’ certainly is.” — J.J. Abrams,

The seed for “Cloverfield” was planted in June 2006 while producer, writer and director J.J. Abrams and his son were on a publicity tour in Japan for Paramount’s “Mission: Impossible III.” The creator of the hit TV series “Felicity,” “Alias” and “Lost,” who made his motion picture directorial debut with “MI: III” and will next direct a “Star Trek” feature, stopped by a local toy store with his son, Henry, and noticed a plethora of Godzilla-themed toys. “It struck me that here was a monster that has endured, culturally, something which we don’t have in the States,” he says.

Shortly thereafter, Abrams conceived the idea of making a movie involving a new monster, though he realized it would require a substantially different approach from the original “Godzilla” and its numerous sequels and remakes. “I began thinking, what if you were to see a monster the size of a skyscraper, but through the point of view of someone, relatively speaking, the size of a grain of sand? To see it not from God’s eye or a director’s or from an omnipotent point of view.”

Abrams contacted frequent collaborator Drew Goddard, the screenwriter with whom he had worked on both “Alias” and “Lost.” “J.J. called me and said, `Drew, I’ve got to talk to you — it’s about something huge,'” the writer recalls. “At that point, all he had was the basic framework of a movie about a giant monster, but shot with a handheld camera. I immediately said, `I’m in.'”

“Drew was the first person I thought of, because he knows how to combine spectacle, genre and monsters with comedy and humanity,” says Abrams.

Adds producer Bryan Burk, “This was definitely going to be a genre piece, but we really wanted it to be about the people going through this experience, to make it an emotional movie. There was no one that we knew in our world who was more perfect for that than Drew.”

Abrams and Goddard met a week later and hammered out the film’s first act in a five-page treatment, which Goddard expanded into a 58-page outline over the Christmas holiday break.

The idea of, as Abrams puts it, “a Cameron Crowe movie meets `Godzilla’ meets `Blair Witch Project'” was then pitched to Paramount senior executives Brad Weston and Brad Grey, who were immediately taken with the concept and gave it the green light. “Everybody at the studio said, `We get it. Really, can you do this?’ and we said, `Yes,'” recalls Burk. Adds Goddard, “It was the exact opposite of everything you hear about Hollywood. Everyone was immediately onboard, and it was really this dream experience.”

“I think it is rare for a movie to live up to your expectations,” notes executive producer Sherryl Clark. “I continue to be as excited about it now that it is finished as I was when it was a 5 page treatment.”

As Goddard proceeded to develop the script, the producers began thinking of a choice for director, eventually settling on Matt Reeves. Abrams and Reeves had been friends — and fellow filmmakers – since childhood. They met at age 13 when both entered an 8mm film festival. The two eventually created the hit TV series “Felicity” in 1998, and have remained close collaborators ever since.

Though Reeves might at first have seemed an unusual candidate, since he had no experience in genre projects or with visual effects, Abrams knew he was the right man for the job. “This movie is completely counter to everything I’ve ever seen Matt do,” Abrams says.

“But the reason I chose Matt is because I know he has always principally been concerned with character, and that he would apply a scrutiny to the heart of each character that many other commercial or video directors might not. So many horror movies we see today are sort of torture-porn, ultra-hyper-violent, but there’s nothing about them you can relate to.”

And truly, the film’s focus is not so much on a giant monster wreaking havoc on New York City, but on a group of people undergoing an extreme crisis. “Cloverfield” centers on a group of friends who, at the start of the evening, have gathered at a bon voyage party for Rob (Michael Stahl-David), who is moving to Japan. Another friend, Hud (T.J. Miller), is assigned to document the event with a camcorder.

“What was intriguing to me about this project,” says Reeves, “is the idea of taking something that has such a huge scale, but filming it on an intimate level. The mood emerges from being with these characters. The challenge then became to figure out a way to take something extraordinary and almost absurd — a monster attack — and deal with it in a way that feels utterly real.”

The solution lay in Abrams’ original concept of shooting a film from the point of view of Hud’s camcorder, through which Reeves and screenwriter Goddard interwove the complicated relationships between the characters and their reaction to the monster’s attack.

The first portion of the film features a 20-minute party sequence, during which those relationships are firmly established. “The idea was that if you started a movie that appeared to be all about character, the audience wouldn’t know it was going to be about anything other than that,” Reeves explains. “Then, all of a sudden, after you’ve established this complex network of friends, how they’re related and what’s important to them, we suddenly intrude on this situation with a crazy monster movie, which completely ups the stakes.”

Adds Goddard, “Once the head comes off the Statue of Liberty, you’re not really going to get much of a chance to stop and check in with the characters. So it was important to set up everything we needed before the world fell out from under us.”

Reeves also skillfully interweaves an important storyline throughout the film, that of Rob and Beth’s (Odette Yustman) earlier relationship. Hud is unknowingly taping over an earlier recording Rob had made with the camera of intimate, quiet time spent with his mate. “You see their loving gaze. It’s this small love story,” says Reeves.

“So I began thinking, `Isn’t there some way to make that kind of a parallel story?'” The film actually begins with some of this footage — much of it shot by Michael Stahl-David himself using a small video camera. But additional portions also appear interspersed throughout the movie, typically after some shocking event has caused Hud to briefly shut off the camera, allowing a brief portion of Rob’s original recording to play for the audience before Hud picks up the current action again.

“We’re seeing the aftermath of two people who have longed to be together, and somehow finally come together, crosscut with this other event,” the director explains. “By going back and forth between these two pieces, you end up heightening the drama. By looking back at this relationship and what it could have been, the audience starts to put the pieces together as to why Rob is so eager to rescue her.”

“One of the things we thought was incredibly important in a movie with so much kineticism,” notes Reeves, “was to have places where you could stop and reconnect with the characters. After going through these extreme experiences, we give them a chance to react to what they’ve been through before moving them to the next level. Having these dramatic interludes was extremely important. Without them, you’d just be watching a video game.”

Continue Reading and View the Theatrical Trailer

Cloverfield (2008)

Directed by: Matt Reeves

Starring: Michael Stahl-David, Mike Vogel, Odette Yustman, Lizzy Caplan, Jessica Lucas, Margot Farley, T. J. Miller, Liza Lapira, Lili Mirojnick, Elena Caruso, Maylen Calienes

Screenplay by: Drew Goddard

Production Design by: Martin Whist

Cinematography by: Michael Bonvillain

Film Editing by: Kevin Stitt

Costume Design by: Ellen Mirojnick

Set Decoration by: Robert Greenfield

Art Direction by: Doug J. Meerdink

Visial Effects by: Double Negative, Tippet Studios

Music by: Johnny Greenwood

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for violence, terror and disturbing images.

Studio: Paramount Pictures

Release Date: January 18, 2008

A Hud’s Eye View of a Monster

The result is an adrenaline-charged roller-coaster ride, with the audience’s connection to the characters maintained through the eye of a single camera. The technique lends itself to keeping us in touch both with the characters and with what’s going on around them, in what has become, in recent years, a most familiar style of image capture: the personal camcorder.

“When I first had the idea for the film, I began thinking about the impact of the YouTube-ification of things,” says Abrams. “Today, if you look online for two minutes, you can find video — whether it’s from Iraq, London, Spain or Manhattan — of people hiding in a store or hiding under a car, and watching other people’s reactions.”

Watching such footage — as seen in countless homemade catastrophe videos — has an unusual effect on the viewer. “In this YouTube era, watching this kind of video has a voyeuristic quality, even if you’re just watching people do mundane things,” notes Goddard. “For some reason, when it’s real, you can watch it forever — it’s like you’re intruding on people’s lives.” And we knew that, for the movie to work, it had to feel real — like you’re watching somebody’s party, peeping in on them — so that when the chaos starts, you would automatically transfer that reality to the monster.

The experience was similarly unique for the actors. “You feel like you’re a part of the movie, as opposed to being an outsider,” says Jessica Lucas, who plays Lily in the film. “You really feel like you’re going through this experience with these characters.”

The challenge for the filmmakers was how to recreate this kind of footage for narrative cinematic purposes. “We asked ourselves, `What does it look like when people are videotaping a spontaneous, horrific event?'” says Abrams. “It was an incredible readjustment,” says Reeves, “because, in trying to create the illusion of only one camera, you were working without the usual cinematic tools. So there’s no big wide shot, no reverse shot to show the other person watching and listening. Everything you see and know comes from Hud’s camera and his point of view.”

A limitation on the types of shots available proved to be a key element in the film’s look of authenticity. “It had to feel like something that was not made by experienced filmmakers,” Reeves continues, “but by people who just found themselves in the midst of this situation.”

Adds Burk, “We wanted the film to look like real life, as if a giant monster was attacking my city and I grabbed my camera and ran out into the street — and this would be exactly the footage I’d have.”

Doing so required the development — or, rather, replication — of a visual grammar that gave the impression of a novice using a video camera and trying to capture the frantic chaos around him. “It had to look amateurish,” says director of photography Michael Bonvillain. “It still had to sell the story points, but in this case, as captured by someone who isn’t a trained operator.”

An important quality of this technique — one which adds incredible terror and tension to many scenes — is having the camera operator “just miss” much of the action, including sightings of the monster. “So much of what’s conveyed in real amateur or documentary footage is what you hear but don’t see — the panic and reactions to what’s happening off-camera and the sounds of things you don’t see,” explains Abrams.

“There’s something very scary about what you can’t see,” adds Reeves. “You’re in there with Hud, and there’s no reverse angle showing you what he’s not seeing. They don’t have any more information than you do. Every moment becomes charged, because you know that, just off-frame, there might be something horrible happening. But you don’t know what it is, because he hasn’t turned the camera there yet. It becomes all about what your mind fills in.”

Portraying intriguing action has a curious effect on the audience, says Sherryl Clark. “Picking those moments, and showing just enough to get the audience frightened and excited, leaves them wanting more.”

In “Cloverfield,” the camera often provides only snippets of what has just passed by — i.e., the monster — accompanied by a comment from one of the characters such as “What was that?” or “Can you see it? What is it?”

“The idea is that it all appears to be haphazard, so that you might catch a glimpse of something out of the corner of your eye and you’re not quite sure what it is,” explains visual effects supervisor Michael Ellis. “Hud is very much led by the direction the other characters are giving him. They usually see something before he does, and he tries to find it; but by then, he’s already too late. He’s just missed it. His friends are already running away.”

One difficulty in creating these “amateurish” shots lay in the fact that there were seasoned professionals behind the camera like Chris Hayes. “Chris is amazing,” says Reeves. “But sometimes he’d operate almost too well. I’d say, `I need this to feel more accidental.’ Because, at the end of the day, we wanted it to feel like anybody with a camera could have made this movie.”

A key solution turned out to be a fairly obvious one: have actor T.J. Miller, who plays Hud, operate the camera himself, which he did for a number of sequences. “T.J. actually operated a lot,” explains Bonvillain. “He was always joking that he should have gotten his union card for all the work he did.”

Having Miller operate the camera had several advantages. “For one thing, he had good instincts of what to do, because he is Hud,” Bonvillain continues. “Also, having him operate helped us make sure we were providing the right eyeline for the other actors in the scene, so that it felt correct when people were talking to him.”

“I wasn’t just an actor,” Miller says. “In some ways, I was a cameraman, and in most ways, I was a voice-over artist.”

The experience was, as one would expect, a bit daunting at times, he admits. “It was hard. You know, I’m thinking about camera movement, and ‘Do I shoot over here?,’ and they’d come in and say ‘Okay, we need you to tilt up and then pan left after her line.’ And I’m thinking ‘Okay, cool. And how about the acting? Was that good?’ It was a lot to juggle.

If one of the professional camera operators was shooting a scene, Miller would often stand behind him with his hands on the operator’s shoulders, again, to provide an appropriately realistic eyeline for his fellow cast members. And, in the instances during which the operator had to physically interact with one of the actors as if he were Hud, he would don Miller’s costume.

Orchestrating entire scenes all shot on one camera – some with extremely long takes – took great skill and planning. In a more typical movie, a scene would be made up of cuts photographed from a variety of angles, shot over several takes, each of which would have provided specific information for the scene. In “Cloverfield,” the frenetic camera movement had to be carefully planned out to capture any activity Reeves wanted the audience to see.

“We had to take a lot of things that were really well-rehearsed and find a way to make them seem accidental,” the director explains. Adds Abrams, “Matt did a lot of things that are incredibly complicated — making shots look as if they were continuous and staging things in a way that felt spontaneous, which they hardly were.”

Many of the film’s shots were planned out ahead of time using “previsualization” animation provided by the Los Angeles-based Third Floor, says Michael Ellis. “It helped give the actors and the cameraman some clue as to where they were supposed to be pointing and what exactly it was they were trying to run away from.” If Miller was operating the camera, Reeves and Bonvillain would walk through the scene rehearsal with him. Sometimes they would shoot the rehearsals with a smaller video camera, then massage the scene until it was to their liking, before proceeding to shoot it for real.

Scenes in which the monster is spotted took careful strategizing — again, to limit sightings to “glimpses” during sequences earlier in the film, gradually leading to full-on views as the movie progressed. For the most part, the monster is seen only from ground level, since that’s where Hud is for the majority of the film. “And that creates a very unique perspective,” notes Reeves.

Eventually, though, says Goddard, “We realized that you do owe the audience a shot of the monster.” The aerial, “God’s eye” shots of the monster the audience would see in a traditional film are absent in “Cloverfield” — save for one or two carefully-planned sequences, such as a helicopter shot that Reeves worked into the film. “When they’re in an electronics store and people are watching news coverage on TV sets, you see a helicopter shot of the monster as his tail swings and takes a chunk out of the Brooklyn Bridge,” explains the director.

A more intimate view of the monster occurs when our cameraman, Hud, is attacked by the monster, revealing the inside of the creature’s mouth briefly to the camera before it is spit out and lands on the ground. Reeves notes, “Drew said to me, `To a monster movie fan, the idea of being eaten by a monster — there’s nothing cooler.'”

Casting “Cloverfield”

Given the unique, intimate filming style of “Cloverfield,” the filmmakers sought out actors who were not instantly recognizable faces. Reeves and Abrams assembled a diverse group of gifted young actors: Lizzy Caplan, Jessica Lucas, T. J. Miller, Michael Stahl-David, Mike Vogel and Odette Yustman. It was a strategy Abrams had used with great success before when he helped spark the careers of such actors as Keri Russell, Jennifer Garner, Scott Speedman and Evangeline Lily.

“The key to casting this movie well was to cast really great, talented, likeable people that you hadn’t seen before,” Abrams says. The main reason, says director Matt Reeves, is that “even though we were doing a very large-scale monster movie, we were doing it in a very independent way. And that necessitated us purposely bringing in people we didn’t recognize.”

Cast in the pivotal role of Rob in this unique project is Michael Stahl-David, who last appeared on the critically acclaimed series “The Black Donnellys.” Stahl-David immediately struck up a rapport with director Reeves. “What attracted me to the project was that I haven’t really made a lot of movies. But I really got excited about the prospect of working with Matt during the audition process. I got the sense that he was somebody interested in character and nuance. He got very animated when he talked about the dynamics between the characters. He seemed to appreciate the ‘try this and see what we find’ approach, which made me feel very free.”

The unusual, heard-but-rarely-seen character of Hud fell to T.J. Miller. “I had a meeting with the casting director and we talked about the fact that I’m a comedian,” says Miller, a Second City native.

Though the specifics of the project were kept under wraps during the auditions, Miller was assured he would be allowed to filter his humor into the film. His audition material, however, was anything but funny. “I came in to read and they gave me the material and it was this really heartfelt, serious monologue,” he recalls. “So I was completely confused. The casting director stopped at the end of it and said ‘That was awesome, but it’s definitely the wrong script. My assistant gave you the incorrect monologue. We’re going to get you the right sides.’ They gave me sides that were a little more appropriate to my character — who is an excitable, funny guy you only see for three minutes.”

It was important for the filmmakers to find someone with humor and compassion to portray the film’s narrator. He is an “everyman” in a sea of sophisticated, upwardly mobile Manhattan-ites. “T.J. is us,” says executive producer Clark. “When you watch the movie you are T.J. because the character of Hud has humanity and emotion and a sense of humor. He’s totally relatable. He’s not only the voice of the movie, he’s the heart of the movie.”

“Everybody’s got a friend like Hud,” says producer Bryan Burk. “He’s the guy who’s missing the self-edit button. But he’s also the person that is always there for you when you need him. He’s insane, and you love him.” Adds director Reeves, “We thought, `Okay, well, if you feel that presence behind the camera, that’s something you’re going to remember.'”

Jessica Lucas describes her character, Lily, as “the bossy one. She’s the older sister living in control all the time. She’s the only one of the group who really has her life together. That’s why she’s the organizer who instigates this whole night.”

Vancouver native Lucas, who recently joined the “CSI” team on CBS, had an unusual path to “Cloverfield.” “I got a call from my agents saying that I had an audition for a J.J. Abrams movie. I had no script, no character description, no sides, nothing. There was no way I could prepare for it. And I went on tape for it. I didn’t hear anything and after six weeks I went back on tape for them again. Two weeks later I flew down to meet with J.J., Bryan Burk and Matt, and we did a reading, and they actually told me in the room that I got the part, which was very exciting.”

Executive producer Clark explains the six week silence: “Jessica sent in an audition tape and we overlooked it at first. We had gone through hundreds of actresses and couldn’t find anyone who just had everything we wanted for the role. Our unit production manager said he had just worked with this great actress named Jessica Lucas — and for some reason that rang a bell. So we found her tape, called her and flew her down that day. She auditioned and we cast her in the room and sent her to wardrobe. We started shooting just a few days later.”

Clark’s experience with Lucas during production further solidified her confidence in the young actor’s abilities. “She possesses true star quality. She’s beautiful, charming and she’s got heart. She’s everything we wanted for Lily because she’s in the movie almost more than anyone.”

Odette Yustman had a similarly serendipitous journey to “Cloverfield” portraying Beth, Rob’s love interest. As Clark remembers it, “Matt Reeves, Bryan Burk and I were walking out of another meeting and we decided to stop by the casting office. Odette was sitting in the waiting room, and Alyssa, our casting director, said, `Do you mind sitting in? There’s this girl and I think she’s great.’ We were blown away. We saw her and we knew she was Beth. She’s lovely and so talented and bright.”

The two more recognizable faces in “Cloverfield” belong to Lizzy Caplan (Marlena) and Mike Vogel (Jason). Caplan has had no problem disappearing into roles such as the Goth-like, cynical Janis Ian character in “Mean Girls” or as Kat Warbler in the critically acclaimed series “The Class.” She tackled the role of Marlena with similar gusto. “The thing that attracted me to this movie was J.J. Abrams. I’ve always been really impressed with `Lost,'” she admits. So she wasn’t thrown by the veil of secrecy surrounding her audition. “We didn’t know anything about the movie other than that J.J. was involved. What we read were not scenes from the movie, but from TV shows like ‘Alias.'”

Caplan speculates that Abrams and Reeves were perhaps returning to their roots — the two had first collaborated on “Felicity.” The actors’ first taste of the script was from the early part of the movie, scenes in which six 20-something characters are involved in various unrequited crushes and friendships. “At first I thought it was a coming-of-age movie, sort of like `Reality Bites,'” Caplan recalls. “But then they gave us a second audition scene at the last minute in which I had to stab T.J. Miller in the heart with a shot of adrenaline. The producers were just laughing and loving the fact that we had no idea what was going on.”

The chemistry between Miller and Caplan was critical, says Reeves. “Having T.J. and Lizzy play off each other was what sold us on that relationship. So it was critical that we cast them and develop that relationship.”

Vogel previously starred with Kurt Russell in “Poseidon,” with Jennifer Aniston in “Rumor Has It…” and opposite Jessica Biel in the recent remake of “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.” “Mike has a lot more movie credits under his belt than most of the rest of the cast,”

Clark says. “He was probably the most familiar actor when he came in and read with Michael (Stahl-David). We were trying to pair actors and look for chemistry. There’s a scene in which these two brothers are talking and having a beer. He brought in two beers, and they drank during the audition and it was sort of charming, and real. We just fell in love with Mike, and felt like he really was acting kind of like that older brother. We hired him based on that audition.”

For these six talented actors, the excitement of being cast in a huge science fiction thriller produced by J.J. Abrams came with a proviso: they were forbidden to breathe a word about the movie to anyone, and even had to sign non-disclosure forms.

Building a Better Monster

The visual effects for “Cloverfield” were produced under the direction of visual effects supervisors Kevin Blank, Eric Leven of Tippett Studio and Michael Ellis of London-based Double Negative. Tippett created all the shots that include the monsters, while Double Negative was responsible for all of the other destruction and sequences which did not include the monster.

The concept for the monster (affectionately known simply as “Clover” in-house) is simple, says Abrams. “He’s a baby. He’s brand-new. He’s confused, disoriented and irritable. And he’s been down there in the water for thousands and thousands of years.”

And where is he from? “We don’t say — deliberately,” notes Goddard. “Our movie doesn’t have the scientist in the white lab coat who shows up and explains things like that. We don’t have that scene.”

Not only is the creature disoriented — he’s downright angry. “There are a bunch of smaller things — humans — that are annoying him and shooting at him like a swarm of bees,” observes Reeves. “None of these things are going to kill the monster, but they hurt it and it doesn’t understand. It’s this new environment that it finds frightening.”

For the monster’s design, Abrams engaged veteran creature designer Neville Page, who had just finished creating characters for James Cameron’s upcoming “Avatar” (and is currently working on Abrams’ “Star Trek”).

“So much has been done in so many different movies with large creatures that the trick was to find a way to create a unique character,” explains Abrams. The producer had first become familiar with Page’s work through the designer’s series of instructional DVDs for The Gnoman Workshop. “One of the things that struck me about Neville’s instructional videos was the way he approaches everything from a realistic point of view. He develops non-existing creatures, but can explain to you their physical makeup, musculature and skeletal structure.”

Adds producer Burk, “Neville was the first person we met with. And he’s amazing. He doesn’t just think about designing the creature, he thinks in terms of how it would walk, how it would breathe, what its skin would be like, how it lives — everything.”

Once Page’s designs were complete, it was up to Tippett Studio to implement and refine the monster for inclusion in the few — but crucial — shots in which he appears. “We did a test, where we inserted him into some background plate shot in downtown L.A.,” explains Leven. “We experimented with different looks, in terms of not only the creature itself, but how it would interact with the camera and with light.”

Another facet of the design was added at director Reeves’ suggestion. “I wanted him to have that sort of spooked feeling, the way, when a horse is spooked, you can see the white of its eyes along the bottom. And you see that when the military is firing on him, where he becomes completely agitated and confused.”

As part of a “post-birth ritual,” as Abrams describes it, the monster is seen early on scratching his back on a building (destroying it in the process), to remove a layer of parasites that are set loose to wreak their own havoc on the city.

“Drew and I were struggling with, `When you have a monster that size how do you keep the characters from seeming totally irrelevant?'” says Abrams. “How do you have any one-on-one struggle?” Explains Goddard, “Because he’s so big, we knew it was going to be difficult to have intimate sequences. It’s not like any of the characters could fight him or that anyone could even figure out a way to hurt him.”

And because of that, the idea of the parasites was born. “They’re these horrifying, dog-sized creatures that just scatter around the city and add to the nightmare of the evening,” Abrams says.

“The parasites have a voracious, rabid, bounding nature, but they also have a crab-like crawl,” Reeves explains. “They have the viciousness of a dog, but with the ability to climb walls and stick to things.”

In addition, the parasites also move more rapidly than their giant host counterpart. “Tippett Studio has a lot of expertise with these kinds of fast-moving creatures that can destroy people and rip them to shreds, which is always a lot of fun to work on,” says Leven. “They’re like little whirling dervishes that just destroy anything in their path. They’re totally deadly.”

Crushing The Big Apple

One of the first hints of the destruction brought on by the monster’s devastating tantrums comes early in the film, as the core group of young friends leaves Rob’s party to find out what the commotion outside is all about — only to be greeted by the head of the Statue of Liberty bouncing down the street.

The shot was originally featured in a two-minute teaser trailer filmed in late May 2007, which appeared just a few weeks later attached to Michael Bay’s summer blockbuster “TRANSFORMERS.” The trailer contained a variety of shots, including party scenes, Miss Liberty’s head and other depictions of destruction, all of which were shot prior to the start of production on the film.

“The Liberty head sequence was a huge leap of faith from the studio,” explains Burk. But the trailer had an immediate impact on genre fans. “The reaction was just what we’d hoped for,” notes Abrams. “No one had heard of this movie yet. We didn’t even put a title on it, something the MPAA had never seen before.”

The title of the film, though seemingly cryptic, actually came out of the producers’ desire to keep news of the production quiet until the time was right. “We wanted to make a movie that no one knew about and then let them discover it, the way we used to discover movies growing up,” says Abrams.

Interest in the film, based on just the trailer, has been, to say the least, remarkable. “I certainly didn’t expect the outpouring of curiosity and intense scrutiny of this project,” says executive producer Clark, “or people sneaking onto the set and taking photos and video. It’s been intense. People are very interested in J.J. and what he has to say.”

It was, in fact, one of Abrams’ and Burk’s agents, John Fogelman, who, having seen the word “monster” one too many times in private e-mail correspondence, suggested calling the project “Cloverfield,” after a main street near Abrams’ office in West Los Angeles. “We started working on the movie, and it became like a nickname. But we thought, `There’s no way that’s going to be the title of the movie,'”

Abrams recalls. “We even had another title, `Greyshot,’ the name of the bridge that Rob and Beth are hiding under in Central Park at the end of the film, which we were all set to announce at Comic-Con. But, by that time, the name `Cloverfield’ had already leaked out, and the fans already knew it by that name, so we just decided to stick with that.”

The shocking Liberty head shot was filmed on the Paramount back lot and created originally by Studio City-based Hammerhead Productions (the shot, later reused in the feature film, was advanced by Double Negative to include more detail). It’s Abrams’ homage to John Carpenter’s 1981 film “Escape From New York,” which featured a similar image in its original theatrical poster. “I loved that movie as a kid,” he says, “but one of the things that drove me crazy is the poster had this picture of the head of the Statue of Liberty sitting in the middle of a New York street — but it was never in the movie,” says Abrams. “And I always felt that was such a crazy, scary image, that it had to be in our movie.”

Difficult as it was to give a fictional 25-story monster a sense of authenticity (which for Reeves was crucial to the success of the film), Tippett Studio and Double Negative were further challenged to create scenes of destruction that had to look real to an audience for whom scenes of falling buildings in New York are all too well-etched in their minds.

A few years ago, few people had any idea of what a building looked like when it collapsed. “Now,” says Michael Ellis, “when a building collapses in a particular way and throws off a huge amount of dust, it’s recognizable to everybody.” “Again,” notes Leven, “YouTube has changed the game in terms of visual effects references.”

Double Negative already had experience with similar destruction shots. In this case, though, Ellis notes, “the building is collapsing as a result of being knocked down by an enormous monster, so it has to fall in a specific way.” The cloud dust that results from the buildings’ collapse was created specifically to meet Reeves and Abrams’ requirements. “We did research and development in recreating that kind of dust bowl coming down a street,” says Ellis. The dust cloud’s movement was simulated using fluid dynamics, recreating the specific way in which a huge amount of dust and debris behaves when it’s sent cascading along a canyon of buildings.”

For the actual collapse of the buildings, the two teams worked tirelessly to fulfill Reeves’ desire for realism. “We would model floors of the building on an exterior structure, and then just destroy the building layer by layer,” Leven explains. “We’d start with the glass outside, and then the floors inside. We even built bits of furniture. It’s super time consuming, but everyone involved in this project loves this kind of work — it’s every little boy’s dream to blow stuff up!”

Particularly tricky was creating “shaky” visual effects as seen through what is supposed to be a roughly-handled camcorder. While it is now commonplace for effects houses to employ a team of “match movers,” who track the jump of each frame to the next so the computer-generated characters will move to match, “Cloverfield’s” handheld footage multiplied that challenge exponentially.

“Normally our software can solve most tracking problems with a degree of automation,” says Ellis. “But many of these shots proved too complex. It was a humongous task; we had people tracking the shots by hand, frame-by-frame. Zooming shots are always hard to track, but these shots with their increased jerky handheld nature were very difficult. No gentle smooth movement — the camera was all over the place.”

Among the more familiar landmarks destroyed by the monster was the 125-year-old Brooklyn Bridge, which gets swiped by the monster’s tail. A 50-ft. section of the bridge was constructed at The Downey Stages in Downey, California, surrounded by a 360-degree green screen, which was later replaced by background plate shots taken at the real bridge. The horde of extras hired to portray the stampede of panicking New Yorkers trying to escape the creature through stopped traffic on the bridge actually parked their own cars on the “deck” level of the specially constructed structure to fill out the shot.

To reproduce the rest of the bridge, Ellis’s team photographed and measured the real Brooklyn Bridge, from which a full computer-generated bridge was then built. Ellis and his animators also studied footage of real suspension bridge collapses such as the infamous 1940 collapse of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge in Washington. “We studied it carefully to see how suspension bridges break up and tried to get as much excitement as possible into the shot,” he explains.

While the filmmakers wanted to create as much of that excitement and realism as possible for the audience’s enjoyment, they were also extremely conscientious about the implications of these sequences. “In a lot of ways,” says Reeves, “the monster is kind of a metaphor for our times and the kind of terror we all face. So it was important to find a way to approach those feelings without diminishing or exploiting them, and to do so in a way that wouldn’t be disrespectful.”

The film carefully avoids crossing the line from realistic scares to all-too-painful reminders of recent events — through a unique point-of-view experience, humor, and Reeves’ reconnection of the audience with the characters throughout the film. The visual effects teams even took care that the collapsing buildings in the film were older-looking structures that did not evoke the style of the structures that were attacked six years earlier.

Stirring up uncomfortable feelings is not entirely without purpose for a monster movie, Abrams notes. It’s a standard of the genre. “‘Godzilla’ came out in 1954 in the shadow of the bomb being dropped in Japan. Culturally, you had people living with this terror they had experienced — but in the guise of something absurd and preposterous. My guess is that it enabled people in Japan to have a catharsis.”

“To me, that’s one of the most potentially impactful aspects of this movie,” he continues. “It takes so many images that are so familiar, that are potentially horrifyingly scary, and puts them in a context that is ludicrous and laughable, so that people can experience catharsis in a way that doesn’t feel like they’re going through therapy. People have a hunger to experience that, and to process the terror we all live with in a way that doesn’t feel like you’re getting a social studies lesson. And at the end of the day, whether or not that’s something they’re aware of, this movie allows them to have that release. And for younger kids,” he says, “you just have one heck of a great monster movie.”

Fear Itself: Monsters At the Movies

“In the same way that ‘Godzilla’ was about the anxiety of the nuclear age, and the atomic bomb and Hiroshima, the monster in `Cloverfield’ is a metaphor for our times and being able to find a way to approach those feelings without diminishing or exploiting them.” — Matt Reeves, Director, “Cloverfield”

Dracula. Godzilla. Freddy Krueger. Foreboding, violent monsters (in human, animal or alien form) who wreak havoc on an innocent public, have been drawing audiences to theaters since the silent era, offering catharsis from personal anxiety and serving as metaphors for the general fears plaguing the culture during a particular era.

Some of the earliest movie monsters hail from the German expressionist film movement that began during World War I and continued through the 1920s. The central fiends in such films as Paul Wegener’s “The Golem,” Robert Wiene’s “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari” and F.W. Murnau’s “Nosferatu” were controversial depictions of the malaise in war-devastated Germany. Those films were a direct influence on iconic American movie monsters of the `20s and `30s, including “Frankenstein,” “Dracula,” “The Phantom of the Opera” and “The Invisible Man” — exotic foreign demons during an era of pronounced xenophobia and isolationism in the U.S. Not coincidentally, the film’s villains often preyed upon scantily clad females at a time when the country’s inbred Puritanism was being challenged by the “Roaring `20s,” a period of change for women, who not only won the right to vote, but also to bob their hair, raise their hemlines and dance the Charleston.

In the 1940s and 1950s, the monsters became even more menacing, expressing the paranoia and sense of impending doom that characterized the Cold War period. Despite Franklin Roosevelt’s soothing Depression-era promise, there seemed to be something more to fear than fear itself. Movies like “The Thing” and “The War of the Worlds” were populated by mutant beings or evil extraterrestrials bent on destroying the American way of life. The alien invaders in “The Day the Earth Stood Still” could be seen to represent the threat of ideological takeover by communist Russia, while “Invasion of the Body Snatchers” was a thinly-veiled critique of Joseph McCarthy’s “communist under every bed” hysteria. Ironically, the country’s greatest weapons were of little use against creatures like “Godzilla,” a horrifying by-product of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, while the giant ants in “Them!” raised serious questions about the safety of using nuclear power.

The gloomy foreboding of the `50s monster movies was mitigated by the public’s faith in the power of the central government to pull together to tackle these threats. They had, after all, proved victorious in World War II, which was followed by one of the biggest economic booms in our history. Concurrently, as in the 1920s, the country’s conservative, puritanical streak resurfaced in Alfred Hitchcock’s “Psycho” and “The Birds,” which spotlighted two very different kinds of monsters, who exacted revenge on women who too freely expressed their desire for independence.

But by the 1960s and 1970s, that safety net was frayed and the public’s blind belief in their leaders’ ability to save them in a time of crisis came under serious scrutiny. In these films, if disaster struck, it was every man for himself. The monsters in “Jaws” and “Alien” were all the more frightening because they prospered through greed with little regard for public safety. What was good for General Motors…

As the Vietnam War shook the country’s faith in their government, it also influenced writers, philosophers and theologians to question the metaphysical implications of these events. A significant trend in horror movies dealt indirectly with the war (George A. Romero’s landmark 1968 zombie thriller “Night of the Living Dead” — which also included references to the civil rights movement), while Tobe Hooper’s 1974 classic “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre played on fears about the dissolution of the traditional American family. In these movies, we saw the enemy — and it was us.

The idea of God turning away from society surfaced during movies of the era, introducing the scariest monster of them all — Satan. Roman Polanski’s “Rosemary’s Baby,” William Friedkin’s “The Exorcist” and Richard Donner’s “The Omen” made this villain of all villains more tangible (and horrifying) by having him inhabit the body of a child.

If the devil himself could appear in the most unlikely of places, then clearly no one was safe — not even suburbanites. By the 1980s, the exodus away from the dangers of city life (drugs, racial tension, sexual license) to the controlled family-friendly environment of planned communities proved to be no panacea for the happy family in “Poltergeist,” who had unwittingly upset the natural order (again due to greedy, unscrupulous land developers) by moving into a house built on a sacred Native American burial ground. Again, revenge was taken out on the most vulnerable among us — the children.

The sexually maladjusted Norman Bates in Alfred Hitchcock’s “Psycho” evolved into an army of crazed and tormented monsters like Jason in the “Friday the 13th” series, Michael Meyers in “Halloween” and “Nightmare on Elm Street’s” Freddie Krueger. The message to the teens who populated (and watched) these movies couldn’t have been clearer: You have sex, you die. Things went from bad to worse in films like “The Hunger” and David Cronenberg’s remake of “The Fly,” which evoked the AIDS epidemic and the explosion of other sexually transmitted diseases.

With the end of the Cold War, the monsters of the 1990s turned out to be the seemingly normal next-door neighbor who turned out to be a pedophile, a crazed fan or a cannibalistic mass murderer: Dr. Hannibal Lecter of “The Silence of the Lambs,”; Annie Wilkes in “Misery”; and John Doe in “Se7en.”

But, just as the new millennium began, incomprehensible real-life horror overshadowed anything that was being shown in theaters. Not only was the country’s always-fragile sense of vulnerability truly challenged for the first time since Pearl Harbor, but it seemed like a prelude to the end of days. Everywhere one turned there was another potential devastation — Ebola, SARS, bird flu, anthrax and global warming.

And movies responded with films like “28 Days Later,” a contemporary remake of “Body Snatchers” called “The Invasion” and, most recently, “I Am Legend.” Xenophobia resurfaced in a more diabolical manner in films like “Hostel,” “Saw” and “Touristas” — torture fests that eerily coincided with a heated debate over the use of torture in wartime. And in another remake, “Poseidon,” the monster was a tsunami-like wave, not unlike the one that had overwhelmed Southeast Asia only months before.

In Steven Spielberg’s frightening remake of “War of the Worlds” aliens, without provocation, lay waste to the earth — and we are unable to stop them. It’s the earth’s atmosphere — replete with bacteria and viruses — that finally destroys them. Mother Nature came to our rescue, but there wasn’t much to be happy about, since she also gave us the cold shoulder in “The Day After Tomorrow.” Most of North America is covered with a blanket of ice and, as in “War of the Worlds,” it has happened without so much as a warning (or maybe we weren’t listening), making the U.S. largely uninhabitable.

The nature of new, previously unforeseen threats to our way of life, has led to a new breed of monster movie that reflects not only the uncertainty of our era, but our sense of powerlessness in the face of such daunting obstacles.

Cloverfield (2008)

Directed by: Matt Reeves

Starring: Michael Stahl-David, Mike Vogel, Odette Yustman, Lizzy Caplan, Jessica Lucas, Margot Farley, T. J. Miller, Liza Lapira, Lili Mirojnick, Elena Caruso, Maylen Calienes

Screenplay by: Drew Goddard

Production Design by: Martin Whist

Cinematography by: Michael Bonvillain

Film Editing by: Kevin Stitt

Costume Design by: Ellen Mirojnick

Set Decoration by: Robert Greenfield

Art Direction by: Doug J. Meerdink

Visial Effects by: Double Negative, Tippet Studios

Music by: Johnny Greenwood

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for violence, terror and disturbing images.

Studio: Paramount Pictures

Release Date: January 18, 2008

Views: 83