Taglines: The biggest risk in life is not taking one.

Proof opens with Catherine (Gwyneth Paltrow) talking to her father Robert (Anthony Hopkins) after he startles her watching TV in the middle of the night. He gives her a bottle of champagne for her birthday, which she starts drinking from the bottle, commenting on how bad it is. They chat for a while about the nature of insanity and how he is crazy, but then she challenges his admission that he is crazy, pointing out that he had just admitted that the nature of insanity is that you can’t acknowledge your own insanity. He reminds her that he’s not just crazy he died last week and his funeral is tomorrow.

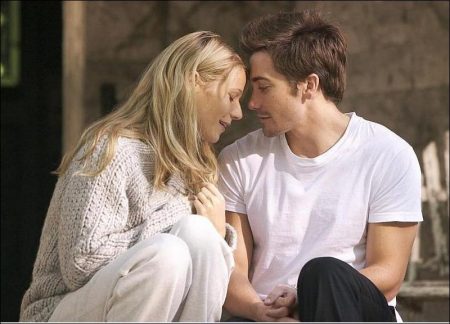

Awoken from this dream, Catherine realizes that there is someone still upstairs — Hal (Jake Gyllenhaal), a former student of Robert’s. Robert was a professor in the University of Chicago’s math department and Hal is a fledgling mathematician, struggling to advance in the field with any sort of developments of his own. In his younger years, Robert had made many advances in mathematics, revolutionizing the field twice before 22, and is quite famous and well regarded for it, but struggled with mental illness for the last 20+ years of his life.

Catherine asks him why he is still there and he confesses that he thinks that somewhere in Robert’s books of notes there has to be additional products of his mathematical genius. Catherine asks him what there has been in the notes he’s made it through. Hal confirms that it was gibberish, but tells her that it would make a career for someone to find even a fraction of the advances Robert made in his early to mid twenties.

She asks if he is trying to steal her father’s work, and he says that, no, he would credit the discovery to her father. She demands to see his backpack and pulls it off of his back, dumping it out while trying to find any of her father’s belongings. Nothing found, she apologizes and he gets ready to leave. As he’s walking out the door she picks up his folded up coat from a chair, thinking he is forgetting the garment, but a notebook falls out. She yells at him, and calls the cops, but he tells her that he was going to give it to her as a present because it has something complimentary written about her in it. He leaves, and the cops pull up, but she sends them away.

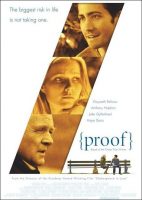

Proof is a 2005 American drama film directed by John Madden and starring Gwyneth Paltrow, Anthony Hopkins, Jake Gyllenhaal, and Hope Davis. It was written by Rebecca Miller, based on David Auburn’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play Proof. The film opened at #35 in its opening weekend with $193,840 and went on to gross a mild $7,535,331 in the USA and $14,189,860 worldwide.

Director’s Statement

In mathematics, solutions to unimaginably complex problems may be found by the application of a rigorous set of rules. Hypotheses are subjected to a sequence of deductions which can lead, if the right route is followed, to an unequivocal result: a proof.

In life we search for solutions, too, but the rules are subjective and fluid and must be negotiated. Who are we? What do we know about ourselves? What can we trust in our relationships with others? We crave certainty and assurance, but have to draw conclusions from incomplete evidence. And as a result those conclusions can seem provisional or invalid.

This film explores a mystery whose solution lies somewhere between the certainties of mathematics and the shifting perspectives of human experience, and deals with intangible values that are difficult to verify: trust, love and sanity.

The Genesis of the Film

David Auburn’s play ‘Proof’ premiered at the Manhattan Theater Club in May 2000, and transferred to Broadway’s Walter Kerr Theater on October 24, 2000. It went on to become the longest running play since ‘Amadeus’.

Jeff Sharp, a partner in New York based production company Hart Sharp Entertainment (‘Boys Don’t Cry’, ‘You Can Count on Me’) first read the play in script form prior to its initial production at the Manhattan Theater Club.

He was immediately taken by Auburn’s writing. “I loved David’s work and I felt that this was the beginning of the major career of a major playwright. I didn’t see it as a film on the page and it wasn’t until I saw the play that I realized its cinematic potential,” said Sharp.

John Hart, Sharp’s producing partner added, “I went to a matinee with Robert Kessel (another of the film’s producers) and immediately fell in love with the play. I thought there was an elegance to it and that we should do everything we could to shepard the play into a film. Many people will option works and then not necessarily make them; we don’t option that much and what we do option, we make.”

To this end Hart and Sharp met David Auburn and outlined their ideas for the film. Sharp explains, “We told David that we saw PROOF as a film much in the tradition of our previous films. David was thrilled that we had produced ‘You Can Count on Me’ as that happened to be his favorite film from the previous year and because it was based on a piece by Kenneth Lonergan, who is also a playwright.”

In the subsequent months, Auburn’s play went on to win the 2001 Pulitzer Prize for Drama and the 2001 Tony Award for Best Play, Best Director (Daniel Sullivan) and Best Actress (Mary Louise Parker).

Hart Sharp Entertainment then set about the task of finding the right director for the material. John Hart said, “We always thought John Madden was the ideal choice for this project. He read the play, and really loved the writing but didn’t initially see it as a movie. But by a unusual sequence of events, he came back to the piece via his own stage production in London, and began to feel differently about its life on the screen”.

Gwyneth Paltrow had some time before been approached by Hart Sharp to play the role of Catherine. She had a wonderful experience playing Catherine on stage at the Donmar under John Madden’s direction in her London theater debut, and the performance was universally acclaimed by a sceptical critical community.

Because it was all such a positive experience, she agreed to take it on, explaining: “We didn’t know what schedules would allow and John wanted to see whether it was crackable as a screenplay, but we were both so attached to the material and had such an amazing experience doing the play that we were determined to try and make it work as a film.”

Later in the process, when it had been decided to shoot a good deal of the film in the U.K., Alison Owen (‘Sylvia’, ‘Elizabeth’) became involved in the project as part of the production team.

Owen had this to say about working with John, “John cares so much – it’s extraordinary. I’ve never worked with anybody who’s more passionate and intense about his work. He has thought everything through and despite the fact that he plans everything so meticulously and has thought about everything in such detail he still keeps a real fluidity and spontaneity about what he does. He is a master of his art – I’d be happy to never work with anybody else – he’s glorious to work with.”

Hope Davis who plays Claire agreed, “I hope that John asks me to do something else with him in the future. He is really energetic and focused and understands every single word of this material having also worked on the play; he even seems to know the dialogue by heart. It’s wonderful to see him when I’m watching filming – he’s sitting by the monitor and he’s mouthing the words with the actors as they go through it. He’s so involved in it and he just loves shooting and he’s been so much fun to work with. It’s been one of those rare opportunities that every time the director approaches you to give you a note, you know that it’s going to help you.”

Proof marks Gwyneth Paltrow’s third collaboration with director John Madden. “I think that John is just extraordinary because he always finds the truth and he really has an idea and an instinct for what the emotional truth is, and how to tell it. His images are very beautiful and he’s a really great story teller and such a lovely man – so nice to be around every day,” said Paltrow.

From Stage to Screen

In April of 2002, Madden wasn’t thinking so much about how to adapt Proof as a film; he was more pre-occupied with directing the play.

Madden explains, “The Donmar is a small, intimate space, and we had decided to strip the physical world of the play back to its essentials, to the deck of the porch and its roof, pretty much. The set revolved between the scenes, isolating Catherine in a kind of subjective space – it suggested someone turning an idea around in their head. This also had the effect of pushing the actors forward, exposing them, making them almost tangible– the front rows could literally reach out and touch them. It struck me that I kept being told how cinematic the experience was – that it felt somehow like watching a film.”

Madden started to think about the essential elements, “The writing is so good, the emotional landscape so intense, the characterization very rich and accurate, the story is in a way simple yet full of surprises, and there is a really uncanny degree of naturalism to it. It’s also an extremely subjective piece. And it jumps around in time. And it’s a mystery story. And it’s about people’s feelings, very close up. Naturalism, subjectivity, timejumps, mystery, close-ups: all things a movie can do really well. The issue was to figure out how.”

The usual tasks of cinematic adaptation applied, of course – how to open the world up – but paradoxically part of its strength came from the singularity of its focus. The exciting challenge, Madden felt, was structural: to find a cinematic language that could honor the play’s surprises, and develop the mystery so that head and heart were engaged all the way to the end: to synchronize the emotional resolution of the story and the solution to its central mystery. He started the think about the film in mathematical terms, building on the thematic ideas of the play: problem and solution, conjecture and proof.

Madden explains, “David and I discussed a bunch of fundamental issues: how much to open it out? Whether to retain the envelope of time in which the play occurs? Whether to work with the long paragraphs of theatrical composition, or the shorter ones more usual in cinema?”

David saw immediately that there were opportunities to include things the play had only been able to hint at: the funeral, for instance, and the party, but in opening it up did not want to lose the intensity of the original. Rebecca Miller’s contribution was to ask some structural questions, and to come up with some good answers. And perhaps the breakthrough was to realize they could focus on the act that precedes the beginning of the play: what circumstances led Catherine to lock this proof in the drawer in her father’s desk.

Madden offers, “ I felt that if the film could be targeted in a way on that moment, the structure was much easier to sort out. You have one narrative in the present that reveals a mystery, and another in the past which explains it. The one in the past ends by explaining the moment which began the story in the present. Realizing that you could see that moment suggested the structure. What made the story exciting to imagine as a film was that the audience could be engaged with Catherine’s experience at two levels simultaneously: the objective level of the narrative – what exactly happened when – and the subjective – what might be true and what might be imagined.”

Proof (2005)

Directed by: John Madden

Starring: Gwyneth Paltrow, Jake Gyllenhaal, Anthony Hopkins, Hope Davis, Anne Witmann, Leigh Zimmerman, Tobiasz Daszkiewicz, Danny McCarthy, Leigh Zimmerman

Screenplay by: David Auburn, Rebecca Miller

Production Design by: Alice Normington

Cinematography by: Alwin H. Küchler

Film Editing by: Mick Audsley

Costume Design by: Jill Taylor

Set Decoration by: Barbara Herman-Skelding

Art Direction by: Keith Slote

Music by: Stephen Warbeck

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for some sexual content, and language.

Distributed by: Miramax Films

Release Date: September 16, 2005

Views: 75