Tagline: The future is trying to tell us something.

The Last Mimzy tells the story of two siblings who, after discovering a box of toys sent from the future, begin developing some remarkable talents — terrifying and wonderful. As their parents and teacher notice the kids’ changed behavior, they all find themselves drawn into a unique world. Wilson will play a science teacher, and Richardson is the siblings’ mom.

Based on the acclaimed sci-fi short story by Lewis Padgett, “The Last Mimzy” tells the story of two children who discover a mysterious box that contains some strange devices they think are toys. As the children play with these “toys,” they begin to display higher and higher intelligence levels. Their teacher tells their parents that they seem to have grown beyond genius. Their parents, too, realize something extraordinary is happening. Emma, the younger of the two, tells her confused mother that one of the toys, a beat-up stuffed toy rabbit, is named Mimzy and that “she teaches me things.”

As Emma’s mom becomes increasingly concerned, a blackout shuts down the city and the government traces the source of the power surge to Emma’s family’s house. Things quickly spin wildly out of their control. The children are focused on these strange objects, Mimzy, and the important mission on which they seem to have been sent. When the little girl says that Mimzy contains a most serious message from the future, a scientific scan shows that Mimzy is part extremely high level electronic, and part organic! Everyone realizes that they are involved in something incredible… but exactly what?

About The Story

As an average student with a gifted younger sister, 10-year-old Noah Wilder (Chris O’Neil) concludes that “life sucks.” He and his parents have succumbed to the trappings of today’s world, and a humdrum life. Only his 5 year old sister, Emma (Rhiannon Leigh Wryn), resists them. But during a family vacation, Noah and Emma find a strange box that washes up on shore. At once frightened and captivated, Noah wraps the mysterious object in his beach towel and smuggles it home. Inside the box, Noah and Emma find several curious things: a crystal shaped like a large credit card, a “gelatinous mass” that looks like brain coral, a jagged meteorite-like rock (that later breaks into nine “spinners,”) a sea shell and, most alluring of all, a beat-up stuffed rabbit. It seems to whisper in Emma’s ear, “Mimzy.”

The mysterious rabbit Mimzy telepathically communicates with Emma allowing her to develop astonishing skills. As the kids begin to explore the various toys, seemingly impossible abilities develop in them. Emma discovers the spinners twirl to form a vortex that dematerializes objects placed within it; from the sea shell Noah learns to manipulate nature, taking his school’s science fair by storm when he “instructs” spiders to build an elongated web; and from the crystal to develop the ability to move objects through time and space at his mental bidding.

Each new discovery builds upon the last, and soon the children are in a world of wonder, enthralled by the unbelievable possibilities the toys seem to offer. But Noah and Emma’s unusually blissful state doesn’t go unnoticed by their mother, who senses something is up. Jo Wilder’s (Joely Richardson) instincts are correct but she is unable to see, understand, and therefore articulate what her children are experiencing. When Noah first shows his mother the crystal card, she doesn’t see what he sees. She only sees a piece of slate. Noah and Emma, as children, are able to see the potential in the toys; Jo, the adult stuck in fixed thought patterns, fails to see anything besides the obvious. This failure to think creatively leaves Jo frightened and vulnerable, unable to help either herself or her family.

Worse still, Jo finds herself alone with her fears, coping with a hard-working husband, David (Timothy Hutton), who is absent too much of the time to clue into the nuances of his children’s lives. Even when Noah exhibits uncharacteristic intelligence and creativity at his school’s science fair with a project far in excess of his previous capability, David remains stubbornly myopic.

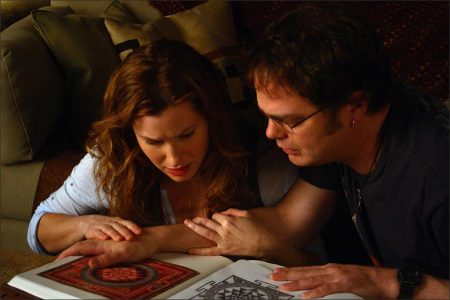

After the fair, Noah’s science teacher, Larry White (Rainn Wilson), is understandably suspicious. White’s curiosity is further piqued when he discovers Noah has been drawing intricate mandalas that mimic the great Buddhist drawings of earlier centuries; and, as if to deepen the mystery, one of Noah’s drawings perfectly mirrors an image that White has seen recurring in his dreams. It’s an astrological configuration representing the past and the future that he first saw during an extended stay in Tibet. But what could possibly be the connection between White, Noah, and ancient Buddhist teachings?

As White and the parents try to decipher exactly what is happening, Larry’s girlfriend Naomi (Kathryn Hahn) develops a theory that perhaps Noah is a “tulkus,” a child believed to be imbued with special knowledge and extraordinary abilities. But to their surprise, it is not Noah, but Emma, who exhibits the telltale signs: “I’ve never seen anything so pure,” exclaims Naomi when she examines Emma’s hand.

Events escalate in the wake of this discovery. Just how far out of everyone’s league this is becomes apparent when the Department of Homeland Security in Seattle, led by Agent Broadman (Michael Clarke Duncan) suspects an act of terrorism, storms the Wilder home and sequesters the family under the Patriot Act. Days earlier, Noah, while experimenting with the toys, had created some form of “generator” that, when accidentally activated, let out a pulse so intense it caused a major blackout through much of the state. Alarmed, the authorities investigate and trace the source of the blackout to the Wilder home. The family is taken to a research facility where agents question them.

The toys are confiscated and put under intense scientific scrutiny, revealing a technology more advanced than anything in existence. Then Emma reveals that their mission is to return Mimzy with something from our genes, to the future, to save humanity. Thwarted in their mission by the authorities, and with Mimzy and the other toys slowly beginning to deteriorate, a desperate Noah and Emma use the skills they have acquired to execute a daring escape from the research facility.

Stealing a van – which Noah has “learned” to drive in a video game – they intend to go to the cottage where two undamaged spinners lay hidden beneath Noah’s bed. Despite having outwitted the authorities, Noah and Emma find themselves stymied by a more mundane foe: the van runs out of gas. But Emma isn’t worried, for she has learned to communicate telepathically, sending a message to Larry in his dreams. Pushed by Naomi into responding, Larry agrees to drive out to the place in his dream, a roadside restaurant where Emma and Noah are waiting.

After being picked up by Naomi and Larry, a distraught Emma cries for the impending loss of Mimzy. She cries and in Emma’s tears is the key for future humanity’s rescue: her DNA. This is because in Emma’s unpolluted DNA are the genes to restore a vital emotion to humanity, a emotion that the future has lost.

At the cottage, Emma and Noah set about creating the time/space bridge that will take Mimzy back to her world, combining what they have learned from the toys to generate a “mandala cocoon” for Mimzy’s flight. But as soon as they achieve this, the authorities and their parents arrive on the scene. Luckily, all arrive too late to stop the process, but to everyone’s shock, Emma is swept up into the energy field that surrounds the cocoon.

Frantic adults all try to penetrate the field but are thrown back by its energy—any moment now Emma will be lost. As the penumbra rises ever higher, Noah suddenly sees a way to save his sister: He wiggles his young body beneath the rising energy field, grabs hold of his sister’s leg and pulls her free just as a wormhole appears above the cocoon and sucks it up. One last blinding burst of energy and Mimzy is gone.

As Jo and David embrace their children, Agent Broadman, unable to comprehend what he has just witnessed, admits that he doesn’t understand but he is sorry for his intrusion into their strange private life. For Larry and Naomi, the night’s events bring resolution and a happy strange coincidence.

Meanwhile, in the future, we see the ultimate impact of Mimzy’s return. Emma’s DNA ultimately unlocks the dormant genes that comprise innocence. Emma, with the help of Mimzy, has returned humanity to mankind.

About The Production

The origins of The Last Mimzy can actually be traced back to 1943. That’s when prolific science fiction author Lewis Padgett (a pen name for the sci-fi writing couple of Henry Kuttner and C.L. Moore) published the short story Mimzy Were The Borogoves in a collection titled Astounding. The story, a simple tale about two children who discover a mysterious box of toys, would eventually provide the inspiration for The Last Mimzy.

Fast forwarding to the 1990s, Academy Award-winning producer Michael Phillips (The Sting, Close Encounters of the Third Kind) came across the original Padgett story as he searched through anthologies of famous science fiction shorts for film ideas.

“I always felt there was undiscovered treasure in there. We went through about a thousand stories, but Mimsy Were the Borogoves immediately captured my imagination,” says Phillips. “My personal taste as a filmmaker is escapist entertainment. I like to go places I’ve never been before, and this story had the kernel of an idea – the idea of two kids finding a box of toys from the future – that was really promising.”

Phillips also saw potential in the story to create a motion picture that was reminiscent of the great sci-fi films of the late 1970s and early 1980s. “This film is, in a way, a throwback to films like ET and Close Encounters in that it’s really about wonder, the wonder of the universe and the incredible things that can be there,” says Phillips. “And it’s about who we are as a species, where we’re going, and how we can determine our destiny by getting back on track – we have gifts and potential we may never have dreamed of. The film presents a really lovely future for us as a species.”

Phillips continues, “So I acquired the rights and brought the idea to Bob Shaye, the head of New Line, who said, ‘I know this story. I’ve loved it ever since I was a kid.’ It was an easy handshake.”

It turned out that Shaye was so intrigued by the serendipity of one of his favorite childhood stories now being pitched to him years later that he not only wanted to make the film at New Line, but he wanted to direct it himself as well.

“It was one of my favorite science fiction stories when I was a kid,” explains Shaye. “After Michael left my office I thought, I’d like to direct this. It just seemed something that would be a lot of fun, especially since I had such passion for the story for so many years. That was the beginning of it.”

Shaye was also drawn to the story because of its timely theme which addresses humanity’s loss of innocence as technology’s influence on our lives grows. “There is scientific evidence that as man becomes more reliant on technology, we could eventually end up losing the gene or combination of genes that create emotionality,” says Shaye. “If we stop using certain genes, they get turned off, and it’s easy to see that if we stop needing innocence that gene could slowly be replaced over many generations. We could forget how to be innocent all together.”

The news of Shaye’s desire to direct the film came as quite a surprise to Phillips, who had previously only dealt with Shaye as an executive. “To be honest, I didn’t know whether that was good news or bad news because I didn’t know Bob as a director, I knew him as an executive,” says Phillips. “It really wasn’t until we started serious pre-production that I saw how incredibly focused he was, that he has the language of film in his blood. And he did an incredible job. This was a tougher film to make than any of us thought. There was the challenge of working in almost every scene with two young children, 340 effects shots, and more than half the scenes required the actors to interact with special effects that would be added later. But Bob was more than up to the challenge.”

In order to tackle the film’s numerous complicated effects sequences, the production actually turned to a trio of companies that specialize in visual effects and assigned each firm its own particular sequence to work on. Visual effects outfit The Orphanage (A Night at the Museum, Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest, Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire) was charged with creating most of the effects, while Rising Sun Pictures (Superman Returns, Batman Begins, The Lord of the Rings: Return of the King) developed the effects for the spiders sequence, and Gentle Giant Studios (X-Men: The Last Stand, The Da Vinci Code, The Chronicles of Narnia) tackled the challenging bridge sequence.

With Shaye on board as director, he and Phillips began to develop the project. Combining Phillips producing savvy with Shaye’s decades of development experience proved useful as the two set out to conquer the challenges inherent in turning a short story into a major motion picture.

“As many short stories do, it didn’t really lend itself to a full-blown feature film,” says Shaye. “The story had to be fleshed out. We wanted a story that grown-ups would respond to and that kids would respond to because there was really something passionate about it. So we took an option on the material and hired a very good writer named James Hart to do a first draft.”

That draft was first commissioned in 1993 and was the launching point for what would eventually become The Last Mimzy. “I’ve been a producer for 35 years, and this was unusual in my experience,” says Phillips. “This film was in development – continuous development – for 12 years.

It went through 19 drafts by five writers. We started with Jim Hart, then Toby Emmerich (who happens to be New Line’s current President of Production, but at the time was the head of its Music division and the writer of the sci-fi feature Frequency), then finally Bruce Joel Rubin. I feel like Jim gave us a body, Toby brought life and a heartbeat to the project, and Bruce gave it wings. It’s been an incredible journey, a roller coaster.”

When Rubin was first approached to write the script, he immediately recognized the story, though he didn’t know its name. “When I was 10-years-old, I watched a television show – I believe it was Science Fiction Theater – and there was an episode about these two children who discover toys from another world,” remembers Rubin. “I thought, ‘This is the most exciting thing I’ve ever seen in my life.’ My little brother Gary and I were glued to the screen, waiting to see what they did with these toys. And then it was over. I looked at my brother and said, ‘This must have been part one. Next week, part two.’ So the next week, Saturday morning, we were in front of the television waiting. Nothing. We were so confused. Years went by and I kept wondering, whatever happened to those kids and those toys and why did I miss that second episode?

“Then, one day Bob Shaye called me about a story called ‘Mimsy Were the Borogoves,’ and I realized, ‘Oh my God, this is that story! Now I’m going to find out what happens at the end.’ But there was no ending. Nothing happens with the toys.”

The open ended story proved so frustrating for Rubin that he initially turned down the opportunity to work on the feature film adaptation. But several drafts later, a version of the screenplay once again came to Rubin’s attention. “Bob sent me a draft that Toby Emmerich had written and it was really good,” says Rubin. “But the ending remained a problem and I kept thinking, ‘What can I do to make this work?’

“I spent a lot of years traveling in Asia, and in Tibet they have a very interesting tradition where when a religious teacher dies, they look for his reincarnation through various mechanisms, one of which is to gather all the toys the teacher had when he was a child and bring them to possible candidates. The toys are mixed in with others and the proof of which child is the true reincarnation is the one that goes to the old toys. I thought this could be the key to the movie’s story. I didn’t know exactly how yet, but this would be the key to this movie. There are toys from the future, and yet these children know what to do with them.”

Summing up his approach to the screenplay, Rubin adds, “This was a movie that I wanted to be about the exploration and discovery of a purity in the human spirit that is something people can look at and touch and watch as it moves through time and space. It is something that is worth preserving. I thought this movie would be a wonderful vehicle for a metaphysical, spiritual, and fable-like mythic story. It has all those possibilities in it. It’s such a simple tale but it goes deep. I only want to write movies that have some reason for being in our culture – most of the stories out there just take your mind away for two hours and give nothing back. I don’t want to tell those stories. I want a movie where you get something that lingers, that embeds itself inside you and changes you a little bit. I think The Last Mimzy is that story.”

Michael Phillips sums up the production that began more than a decade ago with him scouring classic sci-fi literature. “This has been a labor of love for me,” says Phillips. “I think it’s got a chance of being a film that endures. The barometer for me is originality; as a producer that’s what I really look for. I believe that if you find an original, imaginative idea, and you’re able to present it well, the audience will respond.”

About The Ensemble

Finding children, especially very young children, who are talented enough to meet the needs of their characters and the demands of a production is difficult enough when they are peripheral characters, and even more so when they must carry the film. For help, Shaye and Phillips turned to casting director Margery Simkin, who has considerable experience casting children.

“Margery encouraged me to reach out, to broaden my imagination, to aim for quality actors,” says Shaye. “To truly go for an ensemble that would bring real heart and comedy and depth to the story.”

Simkin set up casting centers in four major cities, screened the candidates and then presented the best to Shaye and Phillips. “From the beginning, Rhiannon was really pretty terrific,” remembers Shaye. “There was just something about her, not only her physical demeanor, but her puckishness that I really liked.”

The search for Rhiannon’s brother in the film led the filmmakers to the discovery a new talent in Chris O’Neil. “It was just one of those moments of destiny, I guess,” says Shaye. “We had seen a number of boys, and we selected four to do a final reading. The day before that happened, Margery said she had just met a kid who was literally almost off the street, and she thought I should see him. So Chris came in and he had already memorized all his lines – said it took him only 20 or 30 minutes because he has a very good memory. So right away, I sensed this kid was unusual. He did an incredible reading. The next day, even though the others were very good, he blew them all away and got the role.”

Shaye continues, “This is Chris’ very first time acting. He never had any experience, except some kind of school district dramatic monologue competition which he won. A Hollywood manager happened to be there, and she got so excited about Chris that she proposed to his father that they come to Los Angeles. The day before our final audition they went to see a well-known agent who handles children, who then called up Margery and said, ‘You’ve got to see this kid.’ And that’s how it all happened.”

But equally important to O’Neil’s individual talent, was the chemistry he had with Wryn. As producer Michael Phillips says, “They were a perfect match. During casting, Bob put them through one of the most difficult scenes and they were spellbinding. We all sat there with our jaws open.”

Director Shaye concurs, adding, “These kids are genuine actors. It’s amazing to see people who are so young and so inexperienced be able to conjure up emotions and characterizations that are so full of life.”

Working with child actors in such pivotal roles was also an interesting experience for their adult co-stars. “I’ve done quite a few films with children, but the pressure wasn’t on them in the same way it was in this film,” says Joely Richardson. “I can tell you Rhiannon and Chris were both phenomenally professional in a way that you wouldn’t expect with children. They coped incredibly well. And when people talk about working with children, what they never tell you is the upside. Children can be incredibly instinctive, which is a beautiful thing to play with. It keeps it very natural – technique goes out the door. These are huge bonuses and one of the reasons I personally love working with children.”

The family dynamic also paid off in the relationship between Timothy Hutton and Joely Richardson. “The parents’ roles are very tricky, because they are just reacting to everything that’s happening with the kids,” remarks Rainn Wilson, who plays Noah’s science teacher. “What’s so great about Joely and Tim is that they’re very complicated people who make these characters a lot richer than they are on the page. You really get a sense of their hopes and dreams and what’s driving them.”

About The Music

The cast of The Last Mimzy were not the only “stars” involved in the film’s production. The original music featured in the film was composed by an all-star team that included legendary Pink Floyd singer Roger Waters and Oscar and Grammy-winning composer Howard Shore (The Lord of the Rings trilogy).

With more than 100 film and television scores to his credit, Shore is one of the leading composers working today. In addition to his work on the Lord of the Rings trilogy whose soundtrack has sold more than six million copies worldwide, Shore has scored such remarkable films as The Departed, A History of Violence, The Aviator, Silence of the Lambs, Philadelphia and The Fly.

Waters recorded the original song “Hello (I Love You),” specifically for the film, marking only the second time the rock icon has ever recorded an original song for a motion picture, while Shore composed the film’s score. Waters collaborated with Shore and Grammy Award-winning Pink Floyd producer James Guthrie (The Wall) to record the song, which also features a team of leading musicians including drummer Steve Gadd (Eric Clapton, Paul Simon), guitarist Gerry Leonard (music director/guitarist for David Bowie), and Waters on bass and vocals. The Last Mimzy’s 6-year-old star Rhiannon Leigh Wrynn also appears on the track, singing along with Waters on the song’s chorus.

“It was great collaborating with Bob Shaye and Howard Shore on this film,” says Waters. “I think together we’ve come up with a song that captures the themes of the movie, the clash between humanity’s best and worst instincts, and how a child’s innocence wins the day.”

The Last Mimzy (2007)

Directed by: Bob Shaye

Starring: Joely Richardson, Timothy Hutton, Michael Clark Duncan, Chris O’Neil, Rainn Wilson, Rhiannon Leigh Wryn, Kathryn Hahn, Kirsten Alter, Nicole Muñoz, Megan McKinnon

Screenplay by: James V. Har

Production Design by: Barry Chusid

Cinematography by: J. Michael Muro

Film Editing by: Alan Heim

Costume Design by: Karen L. Matthews

Set Decoration by: Shannon Gottlieb

Art Direction by: Ross Dempster

Music by: Howard Shore

MPAA Rating: PG for thematic elements, mild peril and language.

Distributed by: New Line Cinema

Release Date: March 23, 2007

Views: 58