Tagline: Once discovered, it was changed forever.

The New World is an epic adventure set amid the encounter of European and Native American cultures following the founding of the Jamestown Settlement in 1607. Inspired by the legend of John Smith and Pocahontas, this classic story into a sweeping exploration of love, loss and discovery, both a celebration and an elegy of the America that was–and the America that was yet to come.

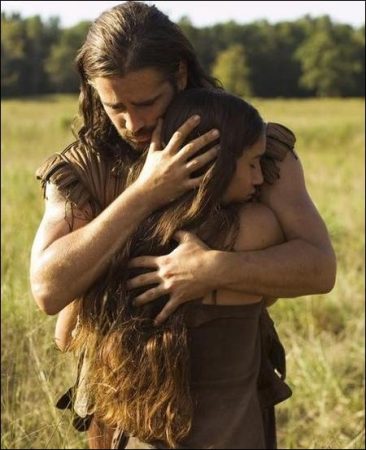

Against a historically accurate Virginia backdrop, Malick has set a dramatized tale of two strong-willed characters-a passionate and noble young native woman and an ambitious soldier of fortune-torn between the undeniable requirements of their civic duty and the inescapable demands of the human heart.

…in the beginning all the World was America, and more so than it is now.” – John Locke, Second Treatise on government (1690)

The New World is an epic adventure set amid the encounter of European and Native American cultures during founding of Jamestown settlement in 1607. Inspired by the legend of John Smith and Pocahontas, acclaimed filmmaker Terrence Malick transforms this classic story into a sweeping exploration of love, loss and discovery, both a celebration and an elegy of the America that was…and the America that was yet to come.

Against the dramatic and historically rich backdrop of a pristine Eden inhabited by a great native civilization, Malick (Badlands, Days of Heaven, The Thin Red Line) has set a dramatized tale of two strong-willed characters, a passionate and noble young native woman and an ambitious soldier of fortune who find themselves torn between the undeniable requirements of civic duty and the inescapable demands of the heart.

In the early years of the 17th century, North America is much as it has been for the previous five thousand years — a vast land of seemingly endless primeval wilderness populated by an intricate network of tribal cultures. Although these nations live in graceful harmony with their environment, their relations with each other are a bit more uneasy. All it will take to upset the balance is an intrusion from the outside.

On a spring day in April of 1607, three diminutive ships bearing 103 men sail into this world from their unimaginably distant home, the island kingdom of England, three thousand miles to the east across a vast ocean. On behalf of their sponsor, the royally chartered Virginia Company, they are seeking to establish a cultural, religious, and economic foothold on the coast of what they regard as the New World.

The lead ship of the tiny flotilla is called the Susan Constant. Shackled below decks is a rebellious 27-year-old named John Smith (Colin Farrell), sentenced to be hanged for insubordination.

A veteran of countless European wars, Smith is a soldier of fortune…though fortune has often turned its back on him. Still, he is too talented and popular to have his neck stretched by his own people, and so he is freed by Captain Christopher Newport (Christopher Plummer) soon after the Susan Constant drops anchor. As Captain Newport knows — and the colonists will soon discover — surviving in this unknown wilderness will require the services of every able-bodied man…particularly one of Smith’s abilities.

Though they don’t realize it at the time, Newport and his band of British settlers have landed in the midst of a sophisticated Native American empire ruled by the powerful chieftain Powhatan (August Schellenberg). To the colonists, it may be a new world. But to Powhatan and his people, it is an ancient world — and the only one they have ever known.

The English, strangers in a strange land, struggle from the beginning, unable — or, in some cases, stubbornly unwilling — to fend for themselves. Smith, searching for assistance from the local tribesmen, chances upon a young woman who at first seems to be more woodland sprite than human being.

A willful and impetuous young woman whose family and friends affectionately call her “Pocahontas” — or “playful one” — she is the favorite of Powhatan’s children. Before long a bond develops between Smith and Pocahontas (Q’Orianka Kilcher) in her feature starring debut), a bond so powerful that it transcends friendship or even romance — and eventually becomes the basis of one of the most enduring American legends of the past 400 years.

About the Production

America did not begin with Columbus and the Nina, the Pinta and the Santa Maria; nor with the Pilgrims and the Mayflower;nor even with the settlers of what became known as Jamestown, the first permanent English settlement, in 1607…which predated the Plymouth Rock landing by some 30 years.

There were 15,000 years of habitation and culture in Virginia by indigenous peoples who found their world turned upside down by the arrival of newcomers from far distant shores. This powerful story, and its central element of the relationship between Captain John Smith and Pocahontas, daughter of the powerful Native chieftain Powhatan, first attracted Terrence Malick’s interest more than two decades ago.

“Terry first wrote The New World about 25 years ago,” explains producer Sarah Green. “He had the idea in the 1970s, and always kept it in his mind and imagination. The New World has, like all of Terry’s films, a very deep understanding of humanity.”

But as with all of Malick’s work, the film is about so much more than its simple narrative story. “It’s a story of our history as Americans, our flaws, good points, vrtues and, growing awareness, woven through the simplest element of all—that which makes us human – love,” said Green. “It’s a story in which people betray each other, try to get it right, betray each other again, and ultimately learn that there are many truths, and you can only live your own. There are no real heroes and no real villains. Every character is sympathetic, some more than others, and every character is flawed, also some more than others.”

One of the unique elements of The New World is the way in which Malick melds his personal vision of the events that occurred 400 years ago in Jamestown with painstaking historical research of the era.

“We don’t know a lot of what actually happened in 1607,” notes Sarah Green. “What we have to go by are the writings of a few people who were there at the time, John Smith most prominent among them, some of which contradict each other. What we have tried to do is take the myth of John Smith and Pocahontas and use it to serve Terry’s vision of cultures connecting and finding ways to move alongside each other, and the powerful consequences of misunderstanding.

“Creative license is definitely taken,” adds Green. “Like all historical dramas since the ancient Greek playwrights, The New World uses real events—or as much as we know about them—and makes them work for the story that we’re telling. The details and fates of some real-life characters have been altered to support the flow of the story and the dramatic elements. The sequence of certain events has been compressed. This is dramatic interpretation, and not documentary.”

Designing The New World

One of the earliest challenges faced by the production team was determining where to shoot the film. Initially, they were skeptical they would be able to find an area that could adequately resemble the world which European settlers first encountered in America.

“We thought that in a million years there’s no place left in the United States that looks as untouched as the James and Chickahominy Rivers would have been in 1607,” says Green. “We thought it would be in some mysterious place where no one lives, so we looked at obscure regions in Canada where there were hopefully untouched forests and rivers.

“But (production designer) Jack Fisk, who lives in Virginia, felt that we shouldn’t go anywhere else until we saw where it all started. So Terry, Jack and I traveled to see the original site of James Fort, and to the Jamestown Settlement recreation nearby. Then we took a boat up the Chickahominy River to see how the landscape flowed, and we thought, gosh, there are a whole lot of stretches that weren’t quite as settled as we thought they might be. At one point, we came around a bend in the river and saw a big old concrete fish house with a ‘For Sale’ sign on it. We didn’t think we could afford to shoot in Virginia, but with our collective aversion to runaway productions, and with a lot of help from the State of Virginia, we decided that we had to make it work. There’s a look in Virginia that’s nowhere else.”

Green credits the Virginia government with helping make it feasible for the production to shoot in the state where the story took place so many years ago. “The Virginia Film Office really helped pave the way for us to shoot there,” says Green. “The unions wanted us in Virginia, the crews wanted us in Virginia and the actors wanted us in Virginia. Then Governor Warner really threw his weight behind us, and that was it. It’s one of the rare examples of a historical film shooting in almost the exact place where the events originally occurred, and that fish house became the site of the Jamestown fort.”

Threads of History

Since Terrence Malick’s quest for historical accuracy extended into every department, costume designer Jacqueline West found herself faced with the daunting task of authentically clothing the colonists and Natives. It was a challenge the veteran designed was eager to accept.

“As soon as I learned that I would be meeting with Terry, who I so admire, I started doing research and drawings,” West recalls. “So when I went to the meeting, I put some sketches and vivid references down on the table for him for Native costumes. They had a dark, mysterious quality, which was in alignment with what Terry had in mind.”

For inspiration, West buried herself in pre-production research, much of it from her own extensive library of books on American Indians. “Designing the costumes for the English was mainly research and then getting the clothes of the period to look like they’d been through what they had to have gone through getting from Britain to Virginia,” says West. “But I wanted the Natives to have a feeling that we haven’t seen before.”

In designing the costumes, West paid special attention to the nature of the materials used in the era. “Of course, everything they used came from the natural world, and we felt that it would have been both unrealistic and spiritually insulting to use mass produced, artificial materials,” she says. “We started ordering skins and furs, but only of what already existed. Of course, no animals were killed for our purposes. I also relied on the generosity of strangers, such as Chief Robert Two Eagles Green of the Patawomeck Indians of Virginia. He became a great friend and benefactor, giving us a great many deer antlers, turkey feathers and other materials. Chief Green and also Chief Stephen Adkins of the Chickahominy would later say, after appearing in scenes for the film, that they felt like they had gone back to the time of their ancestors and really felt that we tried to portray how animals were respectfully used, and how nothing was wasted. If we accomplished that, even part way, I feel we were successful.”

West and her department found other natural materials, including shells at the seashore and freshwater pearls, which were used as adornments by a people who lived by and with the waters that surrounded them. The wardrobe department was to turn out some 500 costumes with a staff that only numbered 15 from the start of pre-production, many of them from Virginia.

“I was able to find the most talented, hardworking and creative people,” West says. “We had 15 fabricators, a mask maker, a headdress maker, two jewelry makers, a wonderful leather maker, all from the area.”

For the English costumes, West teamed with her longtime collaborator Suzi TurnbulI. “I’ve done three movies with her and I call her my secret weapon,” says West. “Suzi did research in England while I was doing research in the U.S., and we put it all together. The period of James I is not one you often see on film. After exchanging drawings that I would sketch and pre-approve with Terry, Suzi went on a search of all the costume houses of Europe, including England, Spain, France and Italy, to find enough wardrobe for this movie. Then we had two agers working with us full time to make them look worn and used. We’ve built a lot of the English shirts, and made lots of britches as well. I insisted that we prep these clothes in England, where we could obtain homespun fabrics. There’s still a great deal of handmade work being done, and you’ve got to go to the source.”

West’s costumes for the protagonists of the film were carefully designed as extensions of their characters and personalities. “Captain John Smith was tricky, because men in tights can be scary,” says West. “I got my inspiration for his costumes from the swashbuckling adventures, but with authentic period feeling. Men in that time usually had one suit of clothing, because for someone of John Smith’s level in society, it would cost almost as much as if you’d had your portrait done by a painter. Clothing was so at a premium that articles like a leather doublet would be bequeathed to someone in your family…it was that valuable. So John Smith had one outfit, and we had to do a variety of things with it. We also gave him elements of things he’d collected in his world adventures and travels: a Transylvanian dragon earring and a Moorish cape, for example.”

Dressing Pocahontas presented a different set of challenges. “For Pocahontas, Terry wanted the costume to be quite simple at first, indicating a free spirit unencumbered by possessions,” says West. “After she meets John Smith, Pocahontas’ character evolves as she becomes more self conscious, so very gradually she gives up her breech cloth and then her buckskin dress. When the Puritanism of the English is imposed on her, we see her in Western wardrobe with a very constrictive bodice, sleeves, lots of padding, crinolines and petticoats. She almost seems to be imprisoned by her clothing. And that gradually transforms in her wardrobe to almost middle-class English later in the story.”

For Kilcher, her character’s wardrobe proved to be a great help in getting touch with the character. “My costumes were so authentic,which helped to make me feel more like the character,” Kilcher says. “There was a total contrast between what Pocahontas wears in Werowocomoco and then later in the film, with corsets, long dresses and high heels.”

John Smith and Pocahontas were far from the only characters whose costumes received elaborate touches. For the “consummate king” Powhatan, West made an opulent mantle which consisted of four deerskins and 30,000 hand-sewn beads depicting the king’s 34 realms. The piece was re-created mathematically from the original, which is currently on display in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, England. Meanwhile Christian Bale’s John Rolfe was dressed in tweed suits of the period that were befitting a Middle Class Englishman, a cut above the first wave of colonists.

Just as it was important for West to use authentic materials for the English and Native American costumes, she also sought absolute realism in the armor that was required.

“Armor didn’t change much from Elizabethan times until the English Civil Wars in the 1620s, but there’s not a lot of really lovely armor that exists that’s really authentic,” says West. “The period-correct armor was either fabricated by us or was discovered in Italy. I loved Terry’s image of the English coming up from the shore in ungainly, clanking armor into this virgin, pastoral, pristine, utopian landscape and its barely adorned people. The visual analogy is amazing.”

In addition to the costumes, a particularly crucial aspect of The New World’s characters were the hair and makeup designs which called for a variety of looks ranging from colonists in various stages of health to Natives who were walking works of art with elaborate body paint, tattoos and unusual hairstyles.

Responsible for such meticulous work was makeup designer Paul Engelen and his staff, particularly department head makeup John Bayless and key makeup artist David Atherton, as well as hair designer Joani Yarbrough and key hair artist Phillip “Mr. P.” Ivey. Atherton and Yarbrough had long experience working on Native American film projects, including Dances With Wolves, but The New World would push them to the limits of their creativity.

The elaborate designs came about after much trial and error. “We had about four weeks of solid experimentation,” notes Engelen, “developing different techniques, textures and ingredients for the paint.”

Adds John Bayless, “Terry loves texture, and not necessarily anything that looks freshly painted. In The New World, you see a look that has probably not been seen on screen before. We want a look of worn paint that isn’t touched up all of the time so as to look pristine. If we’re shooting in the rain, we want it to look as though the paint had to deal with the rain, so we’ll leave it alone and give it a more natural look.

“Terry wanted us to stay with organic colors, trying to stay away from bright reds, or colors that you can’t find in the nature that surrounded the Natives,” says Bayless. “We’ve actually added clays, sand and mud to get more texture than what you’re normally accustomed to seeing, with the idea that the paint comes from the ground, from the leaves and flowers, very organic in terms of application—by hand or by stick, and not by brushes.”

It got to a point where the Native cast, Core and Zone One warriors began to apply their paint themselves each morning. “They got their hands in there and started developing their own designs, as part of their overall spiritual preparation,” notes Bayless.

Extraordinarily, several warriors said that they discovered their particular patterns while dreaming. “On this movie, one of our primary costumes is our makeup,” says actor Michael Greyeyes. “And every time my character appears in the film, he has a different look. I thought it was a brave move, because it shows a community that was dynamic and not set in stone.

The Natives of The New World

The remarkable diversity of The New World cast includes the Virginia Natives appearing in the film. Actors flocked to the production from all over the United States with representatives of the Kiowa, Seminole, Lakota, Pawnee and, from Virginia itself—the direct descendants of the Powhatan empire—Chickahominy, Pamunkey, Rappahannock, and Upper Mattaponi tribes taking on roles in the film.

Making an extraordinary contribution to The New World were the 17 young men who comprised the Core Warriors, who would be trained in the various skills necessary to portray Algonquian Indians of the time. Hailing from all over North America, with many different tribal affiliations, this multi-talented group would demonstrate their skills at dance, combat and song with amazing physical dexterity.

“They became a tribe of their own for this movie, and it was a very profound thing to watch,” notes Sarah Green. “On a daily basis they blessed each other, cleansed each other with sage, cleansed and asked for protection for us. They created a spirit around the movie that I believe everyone felt.”

Actor/choreography Raoul Trujillo adds, “I was given a chance to choose about 10 of the Core, so I was able to select a group who were all dancers. We have breakdancers, powwow dancers, all kinds, all athletic. I knew them enough to know that bringing them together was going to insure that we had this innate sense of spiritual power in the group. We all took on the task of representing the Powhatan people with a sense of commitment and responsibility.”

The Core also represented a cross-section of Native America. Their group leader was Larry Poirier, a highly experienced actor and filmmaker of Lakota heritage from the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota, a man of deep, quiet convictions with a strong sense of responsibility to the past…and to the future.

The 17 members of the Core underwent an intensive two-week “boot camp” training before the start of filming, which saw them working on song, dance and movement with Trujillo, bow and arrow, spear and gunfire instruction with armorer Vern Crofoot and fight work with stunt coordinator Andy Cheng. Also participating in this training camp were many Native female extras, who learned such traditions as pottery, fish netting, weaving, hides, cooking and sign language from animateur Buck Woodard and adviser Frederic Gleach (the extras portraying the Core Colonists also shared some of this training, working in swordmanship, shallop rowing and the like). Also participating side-by-side with the Core Warriors during much of the preparatory training was Q’orianka Kilcher, who was treated like a little sister.

“The Core was an amazing, amazing group of people,” she later recalled. “Although I’m of South American Indian rather than North American heritage, we all share cultures and problems throughout history, and I was totally accepted by them.”

The commitment to historical accuracy in the film even extended into the challenging area of language. The production team hired Blair Rudes, an Algonquin language expert who was charged with teaching this language to all of the actors portraying Virginia Natives as well as translating large chunks of dialogue from Malick’s script from English to Algonquian. As a result, this tongue—which has been virtually extinct since 1780—will be heard again in the film as a spoken language.

In an effort to establish early on that The New World would be dedicated to a more accurate depiction of Native culture than what is often showcased in “Hollywood” films, the filmmakers invited Chief Stephen Adkins of the Chickahominy Tribe to bless the production before they started shooting. It was the beginning of what blossomed into an excellent relationship between the filmmakers and tribal leaders.

“Early on, we invited the chiefs, the assistant chiefs and the representatives of the Virginia tribes to come and see what we were doing, and participate as much as they liked,” Green recalls. “They were, understandably, suspicious. At our first meeting, Chief Adkins gave me a strong and honest talking to about what this meant to them and how they’d been portrayed in the past. Over time, he became a friend, someone we could call on to answer sensitive questions about ritual and what was appropriate to show. Ultimately, he trusted us enough to appear on screen in a scene with Pocahontas.”

The production’s Native American actors were also impressed with the production’s dedication to accuracy. “I spent a lot of time in Los Angeles, and there were a lot of so-called Native films coming up,” recalls August Schellenberg, who plays Powhatan in the film.

“Some of the scripts were just horrible, and I’d say ‘I’m not interested in doing this. It has nothing to do with Native American people.’ You know, those days of, bless him, Jay Silverheels and ‘You betchum, Red Ryder’ are gone. If something is detrimental to Native people, I will not have anything to do with it whatsoever.” Wes Studi echoed Schellenberg’s beliefs.

“I’m sure that audiences will walk away from the film with a better understanding of the enormous birthing pains that came about in the creation of a nation that we now have,” says Studi. “It’s not always pretty, but sometimes the coming together of two cultures can become a wonderful thing. I think that many of the points brought out in the script will lend itself toward creating a better harmony in the world that we live in today.”

At the very least, many in the Native community are hopeful that The New World will help alleviate some of the misunderstandings about their culture. “I think it’s time that the world knows who we are and I’m hoping that The New World helps to tell that story,” says Chief Adkins. “It remains to be seen, but I’m confident with the exchanges that I’ve had with the folks who put this film together that a lot of the myths surrounding the existence of Indians in Virginia will be dispelled.

At our initial meeting with the producers, we asked them some rather pointed questions, and they didn’t sidestep the issues. I have high hopes that this movie, although historical fiction, will be representative of a way of life that my forebears knew and enjoyed. I hope that it will telegraph to the world some of the injustices that my people faced, and will further let the world know that we still exist today…that we overcame the adversities…that we became stronger, that we are still married to our culture, to our heritage, and that will continue to the end of time.”

A Vision Comes To Life

In the end, The New World represents the telling of a classic story through the eyes of one of this generation’s most distinctive and original filmmakers. And as far as the people in the production are concerned, that story could not have been in any better hands.

“Terry is rather like someone from a distant world who’s stumbled into the world of show business, and refuses to be seduced by it in any way, doing it his way and only his way,” says Plummer. “He’s the master of his dream, his vision, of which we are all the offspring.”

Producer Sarah Green also summed up the experience of working with Malick on the film. “Terry Malick is an extraordinary director,” says Green. “He’s all heart and instinct, and works in a way that is organic and beautiful. His work speaks to the heart of humanity, and gets under your skin. He’s a mystery, a magician and an alchemist. What we accomplished on this film shouldn’t have been possible to accomplish. We do it because we believe in him and in the spirit of the moment. I think he has a trust and a faith in people which comes through in the way he writes and the way he works with them.

“There will be many ways of interpreting The New World,” concludes Green. “I don’t think that the title only refers to what the English colonists called America when they ‘discovered’ it. We were working with the idea that, however far America may have wandered from its true purpose and first promise, that the true America still waits to be discovered – still awaits us.”

The New World (2005)

Directed by: Terrence Malick

Starring: Colin Farrell, Christopher Plummer, Christian Bale, August Schellenberg, Wes Studi, David Thewlis, Q’orianka Kilcher, Kalani Queypo, Ben Mendelsohn

Screenplay by: Terrence Malick

Production Design by: Jack Fisk

Cinematography by: Emmanuel Lubezki

Film Editing by: Richard Chew, Hank Corwin, Saar Klein, Mark Yoshikawa

Costume Design by: Jacqueline West

Set Decoration by: Jim Erickson

Art Direction by: David Crank

Music by: James Horner

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for some intense battle sequences.

Distributed by: New Line Cinema

Release Date: December 25, 2005

Views: 75