Taglines: A Lovers Story.

The Unbearable Lightness of Being movie synopsis. Tomas is a doctor and a lady-killer in 1960s Czechoslovakia, an apolitical man who is struck with love for the bookish country girl Tereza; his more sophisticated sometime lover Sabina eventually accepts their relationship and the two women form an electric friendship. The three are caught up in the events of the Prague Spring (1968), until the Soviet tanks crush the non-violent rebels; their illusions are shattered and their lives change forever.

The Unbearable Lightness of Being is a 1988 American film adaptation of the novel of the same name by Milan Kundera, published in 1984. Director Philip Kaufman and screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière portray the effect on Czechoslovak artistic and intellectual life during the 1968 Prague Spring of socialist liberalization preceding the invasion by the Soviet-led Warsaw Pact that ushered in a period of communist repression. It portrays the moral, political, and psycho-sexual consequences for three bohemian friends: a surgeon, and two female artists with whom he has a sexual relationship.

Film Review: for The Unbearable Lightness of Being

PHILIP KAUFMAN’S ”Unbearable Lightness of Being” begins with much promise, as if it were a ribald fairy tale. ”In Prague in 1968,” says a title card, ”there lived a young doctor named Tomas.” Tomas (Daniel Day-Lewis) comes out of the operating room and goes straight to a pretty nurse waiting in the supply room.

”Take off your clothes,” says Tomas. Forever altering one aspect of playing hard-to-get, the nurse does. On the other side of a frosted-glass window several other hospital employees watch Tomas’s technique with admiration.

”But the woman who understood him best was Sabina,” says a second title card. The film cuts to Tomas and Sabina (Lena Olin) in a frenzied, thoroughly satisfying coupling on the platform bed in her studio – she’s a painter.

Tomas and Sabina share a passion for acrobatic, technically ingenious sex that excludes serious emotional commitment but not nonstop conversation. That’s the wonder of Tomas and Sabina. They can enjoy everything they’re doing while always remaining a little detached. Each is like a movie critic who goes through his job with one part of his mind on the movie, while the part that’s safely outside it criticizes the critic’s reactions and prepares to tell all at any minute.

In the midst of ecstasy, the sweating, exultant Sabina tells Tomas, ”You are the complete opposite of kitsch,” though without defining the term. It makes no difference. It’s clear that, to Sabina, whatever Tomas is doing, he’s doing it right.

Tomas buzzes serenely through the world like a bumblebee, his eye on the next flower even before he has quite exhausted the one he’s with. A third title card: ”Tomas was sent to a spa town to perform an operation.” It’s there that Tomas meets the exceptional young woman who changes the course of his existence, forever altering one aspect of what has seemed to be his lightness of being.

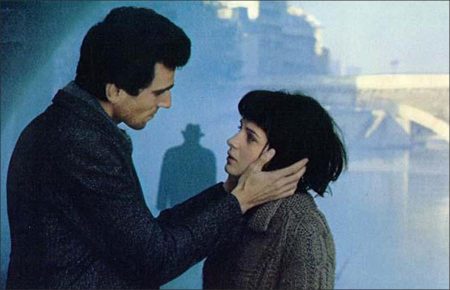

She is Tereza (Juliette Binoche), a romantic waitress who falls profoundly in love with Tomas without knowing anything about him. She follows him back to Prague and, before he’s aware of the consequences, he’s allowing her to sleep the entire night in his bed, something that has always been against his rules. Soon they are married.

After that, ”The Unbearable Lightness of Being” settles down to recapitulate the superficial events of Milan Kundera’s introspective, philosophical novel with fidelity and an accumulating heaviness, as well as at immense length – nearly three hours. It’s possible to read the book in less time.

The film opens today at Loews Tower East. The novel, by the celebrated Czechoslovak writer who now lives in Paris, was adapted by Mr. Kaufman and Jean-Claude Carriere. Mr. Carriere is the French writer whose screenplays (”Belle de Jour,” ”The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie,” among others) for Luis Bunuel exemplify the seamless collaboration possible when a brilliant director meets a brilliant writer who knows the director’s mind better than the director possibly does. Mr. Kaufman’s most recent work was the fine, underappreciated adaptation of Tom Wolfe’s ”Right Stuff.”

These credentials are worth noting. It’s obvious that both Mr. Kaufman and Mr. Carriere understood the problems they faced in making a screen adaptation of a novel whose central character is really a never-seen, loquacious ”I,” representing the novelist spinning the tale. This ”I” is both informally chatty and God-like. He doesn’t participate in the story of Tomas, Sabina, Tereza and the others. He’s looking down on them from a literary ”above.” When it suits him, he briefly enters the characters’ minds and departs, a benign thief in the night.

Mr. Kundera entertains and instructs the reader. He also provokes responses that give point to commonplace misadventures set in momentous times. These are so unspeakably sad that the comic method seems the only civilized alternative to what would otherwise turn into kitsch, something sentimental and false.

Like brain surgeons removing a tumor, Mr. Kaufman and Mr. Carriere have excised the ”I” from the screenplay. Whenever possible, they’ve saved bits and pieces of his observations, which have been reinserted as dialogue spoken by the characters, frequently with a good deal of awkwardness. The ”voice” of the novel is gone. What remains is not exactly bowdlerized Kundera but, even with all the care, intelligence and eroticism that have gone into it, it’s a bit zombie-like. It would be difficult to recognize if one hadn’t known it when it was alive.

Mr. Kundera, whose citizenship was revoked after he left Czechoslovakia, dislikes having his novels and stories parsed for their politics. Yet everything he writes inevitably has strong political meaning, especially in relation to Czechoslovakia, which, landlocked and periodically overrun and cut up by invaders through the centuries, has somehow maintained its own identity.

”The Unbearable Lightness of Being” opens in 1968 during the thaw known as the ”Prague spring,” when everything in politics and the arts seemed possible after the long repression of the Stalinist winter.

As Tomas is drawn against his will into commitment to Tereza, he’s also, briefly, drawn into politics. He writes an ironic essay about the morality of Czechoslovak Communist politicians who admit the errors of their Stalinist days without, like Oedipus, feeling the necessity of purging their guilt.

After the Soviet invasion, Sabina drives off to Switzerland, followed by Tomas and Tereza. When Tereza, feeling bereft with her womanizing husband in a strange country, returns to Czechoslovakia, Tomas follows. He remains committed to Tereza, though still unfaithful. His essay on Oedipus is recalled to haunt him. Tomas becomes a true political activist by remaining resolutely passive. This is the bittersweet joke.

I’m not sure how much of this comes through in the movie since, if one has read the novel, the impulse is to fill in the gaps. Photographed by Sven Nykvist, the film looks beautiful and authentic, but it’s so monotonously paced that it seems to have been edited with the aid of a metronome. Although a good deal of the narrative has been excised, nothing has been condensed. The details of the lives of Tomas, Sabina and Tereza, recalled without Mr. Kundera’s comments, don’t fill the huge landscape provided by the film’s extraordinary running time. It’s literal without even being literary.

Mr. Day-Lewis, Miss Binoche and Miss Olin (who was spectacular in Ingmar Bergman’s ”After the Rehearsal”) are surprisingly fine -both modest and intense as lovers whose private lives are defined by public events. The supporting cast includes Derek de Lint as one of Sabina’s lovers; Erland Josephson in a tiny part, and (listed but unseen by me) Jan Nemec, the excellent Czechoslovak director whose ”Report on the Party and Its Guests” came out during the ”Prague spring.”

Mr. Kaufman attempts to find a common denominator among the various accents by having everyone speak English with a Czechoslovak accent, but even these vary according to each actor’s country of origin. ”The Unbearable Lightness of Being” is notably ambitious and it avoids kitsch. It understands Mr. Kundera, even as it fails to find picture-equivalents to his ideas.

The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1988)

Directed by: Philip Kaufman

Starring: Daniel Day-Lewis, Juliette Binoche, Lena Olin, Derek de Lint, Erland Josephson, Pavel Landovský, Donald Moffat, Stellan Skarsgård, Pascale Kalensky

Screenplay by: Milan Kundera, Jean-Claude Carrière

Production Design by: Pierre Guffroy

Cinematography by: Sven Nykvist

Film Editing by: Vivien Hillgrove Gilliam, Michael Magill, Walter Murch, B.J. Sears

Costume Design by: Ann Roth

Music by: Mark Adler

Distributed by: Orion Pictures

Release Date: February 5, 1988

Visits: 439