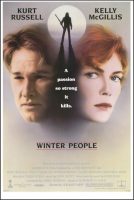

Taglines: A passion so strong it kills.

Winter People movie synopsis. A young widower moves with his daughter into a North Carolina mountain town in 1934. He quickly takes up with a young woman with an illegitimate baby. First he must prove himself to her father and her three brothers. He does so first by joining them on a bear hunt and then by designing a clock tower for the small community. Trouble comes when it is revealed that the baby’s father is the demented son of a mean clan across the river and they mean to take the child back.

Winter People is a 1989 romantic drama film directed by Ted Kotcheff. It stars Kurt Russell and Kelly McGillis. The film is based on the novel by John Ehle. Wayland Jackson, a widower with a young daughter, moves to a small, impoverished mountain village in North Carolina, circa 1934. They are taken in by Collie Wright, a single mother, and she and Wayland soon fall in love.

Film Review for Winter People

I wonder if they realized, while they were making “Winter People,” how similar it was to “Witness” – and how inferior. Both movies star Kelly McGillis, which might have provided the inspiration for a closer look at the recycled similarities, but apparently did not. The plot is like “Witness” turned inside out and played as a “Li’l Abner” parody.

“Winter People” is based on a novel by John Ehle, but it’s almost as if the novel was chosen because it provided an outline for a movie that would try to duplicate the unique success of “Witness.” Consider: “Winter People” stars McGillis as a woman who lives by herself in an isolated community of mountain people. It’s early in the 1930s. She has a young son.

She is an outsider, because the father of the child has not been publicly acknowledged; actually, it’s a young man from the clan that’s feuding with her family. Out of the hills one day comes a peaceful clockmaker (Kurt Russell), a widower with a young daughter. He’s marooned, winter is coming on and he accepts an offer to stay for a while in McGillis’ cabin. Soon they fall in love, but then Russell must defend her and her son against the drunken father of her child.

In “Witness,” McGillis was an Amish widow with a young son, living in an isolated, self-contained community. On a trip to the city, the son witnessed a murder. Harrison Ford was the police detective who later saved them from a violent attack, was nursed back to health by the woman and lived for a time on her farm. The Amish people – especially her father – did not much like the city slicker’s ways. They fell in love, and then Ford had to defend her and her son against the killers who had tracked them down.

The dynamics of the two stories are remarkably similar: isolated single mother, self-contained community, heroic outsider, love, hostility from the community, defense of the new family unit against a violent predator male. The principal difference is that the Amish community is pacifist, and fears the violent outsider; the mountain men are violent, and fear the pacifist outsider. But why do I undertake this exercise in comparison? To try to figure out why “Winter People” is so spineless as a movie. The film is long, dreary and boring, and has the same relationship to “Witness” that a negative number has to a positive number: The shape and form are the same, but there doesn’t seem to be anything there. One of the missing elements is any chemistry between McGillis and Russell, who play their love scenes with a certain studied coolness.

Another problem is with the movie’s whole system of villains. The Campbells are large, unkempt, bearded hillbillies who ride around on horses and shoot their guns and drink moonshine and would have been drawn by Al Capp with flies buzzing around their heads. They have no human dimension. They’re caricatures who ride onscreen, whoop it up, sneer, loot the peaceable clockmaker’s truck, wrap their bullwhips around people’s necks and gallop off across the river. They have no reality or function except as cliches.

The only one who even emerges as an individual is Cole Campbell (Jeffrey Meek), the father of McGillis’ son. He’s a rowdy, out-of-control drunk who staggers in from of the woods from time to time to knock her around. She still seems to care for him in some recess of her soul, and that sets up a speech in which she tells Pop Campbell (Mitchell Ryan) that his son’s troubles were all caused by his fear of his father’s wrath. Given the movie’s reality, this speech is unlikely, but the old man’s response is incredible.

The centerpiece of the movie is a long, violent, showdown between the drunken lout and the gentle clockmaker, and much depends upon the fact that the clockmaker is Scandinavian and likes to swim in ice water. This sets up one of the the most unlikely sequences of events I have ever seen, in which poor Meek is apparently dragged by his horse for miles down a freezing river. In this scene and in others, the movie fails to supply any conviction that it is really, actually cold. The snow looks fake, and the actors walk around outdoors a lot in wet clothing and don’t even shiver.

“Winter People” is the kind of movie where you sit there asking yourself questions that apparently never occurred to the filmmakers. Such as: Why isn’t the passion between McGillis and Russell strong enough to explain the action? Why are the Campbells such stock villains? Has this community any contact at all with the outside world? And even, since the clockmaker’s truck has been overturned and looted, where did he get enough parts to make all those clocks? He makes a lot of clocks in this movie. I wish he would check my watch. About halfway through the film, I shook it to see if it was still running.

Winter People (1989)

Directed by: Ted Kotcheff

Starring: Kurt Russell, Kelly McGillis, Lloyd Bridges, Mitchell Ryan, Jeffrey Meek, Don Michael Paul, Lanny Flaherty, Eileen Ryan, Amelia Burnette, Barbara Freeman

Screenplay by: Carol Sobieski

Production Design by: Ron Foreman

Cinematography by: François Protat

Film Editing by: Thom Noble

Costume Design by: Ruth Morley

Set Decoration by: Leslie Morales

Art Direction by: Chas. Butcher

Music by: John Scott

Distributed by: Columbia Pictures

Release Date: April 14, 1989

Visits: 6222