“When Mike came to me, I told him I was always crazy about the play, I’ve always been crazy about Mike,” says Calley. “On stage and on screen, he has had the ability to transmute the written word into drama in a way that can stop your heart.”

What made Closer inherently cinematic, according to Nichols, was the fact that “it’s told in the way that people remember things — in a telescoped way.” Also, he adds, the element of intimacy in Marber’s work lends itself better to the screen than the stage. “It’s hard to present intimacy in front of a live audience, whereas in a movie the viewer is alone in the dark with the characters, which is in some ways more apt for intimacy, sex and love.”

Marber was very excited by the idea of Nichols directing a film version of his play and was brought aboard to write the screenplay. He says he developed an intimate working relationship with the director, who “wanted me to be faithful to the play. Once he’d established the rule that we’d tell the story pretty much how it was told on stage — in fairly long sequences of time — the job became one of cutting, rewriting and a certain amount of restructuring within the sequences.”

“Mike was fantastically good fun to work with,” he continues. “I’m very fortunate to have learnt ‘on the job’ from a master. Added to that, the catering on a Nichols film is excellent.”

Thematically, Marber asserts that Closer makes no moral pronouncements about the characters’ behavior, allowing the viewer the latitude to make their own assessment. “I’m not concerned with ‘good’ or ‘bad’ here,” he says, “nor in passing judgment on the characters. This is what they said. This is what they did.

How they behaved is really none of my business. The audience will see them as they like, and may well disagree with each other, but hopefully they’ll recognize something true. And laugh at a few of the jokes along the way.”

The screenplay retains the acerbic wit of the play, the intertwining story of two couples, or what producer Cary Brokaw calls “a checkerboard of the relationships between two men and two women that evolves as part of the competition between the two men for each of the women at different times.”

Adds executive producer Celia Costas: It’s a hopeful piece in that the characters come to terms with themselves and change in very interesting ways. They learn something, which is really the most important thing in life………and in movies.”

Up Close: The Players

Dan (Jude Law)

“What’s so great about the truth? Try lying for a change — it’s the currency of the world.”

In Closer, Jude Law portrays Dan, an aspiring novelist who earns a living writing obituaries. Though Marber contends there is no protagonist in the story, Dan is the character through whom all the other characters are introduced. Law is no stranger to portraying vainglorious characters as he demonstrated in his Oscar nominated performance in The Talented Mr. Ripley and, more recently, in Alfie.

What drew him to Closer, which he had seen several times on stage and greatly admired, was Marber’s “extraordinary dialogue and its concentrated focus on these four characters who are the heart of the play,” he says.

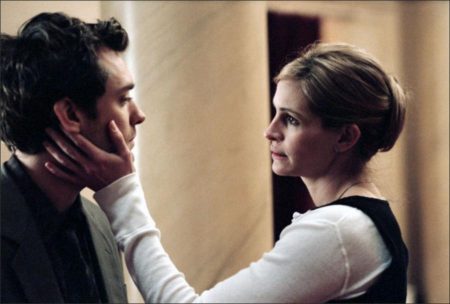

The intimacy of the situation was matched by the demands of working in close quarters with only three other actors. “There was never a day where you could kind of take it easy because virtually every scene has a definite emotional pitch,”

Says Law. “You were either opening up and offering yourself to someone or closing yourself up and trying to get rid of someone. It was quite intense and demanding.”

Reflecting on his character, who is a catalyst for much of the action, Law says, “Dan is someone who’s really living in a sort of cocoon, a frustrated novelist, until he meets Alice, who becomes his muse. Through her, he blossoms. The relationship is really responsible for him coming out of himself, encouraging him to be confident enough to find the woman he really thinks he loves, Anna.

Unfortunately, that relationship seems to be doomed from the get-go, and though it gives him some of the happiest days of his life, he eventually throws himself away by pouring himself so wholeheartedly into it.”

While he sees Marber’s play as basically a story about men and women falling in and out of love, it is also a battle between two male characters who become each other’s nemeses. “There’s a certain amount of ego going on between them. You could argue that for them it is almost more important that they’re screwing over the other guy than getting the girl they’re in love with.”

Anna (Julia Roberts)

“Don’t stop loving me. I can see it draining out of you. It meant nothing. If you love me, you’ll forgive me.”

For Julia Roberts, the character of Anna is a departure, says producer John Calley. “Julia is an astonishing actress who always does what she does wonderfully. But in this case, she challenged herself to explore issues about a strong, intelligent woman in a way that beautifully demonstrates how her considerable talent has evolved over the years.”

“Anna is a compelling woman who understands what she wants, even as it changes and in playing her, Julia shows herself in a way we’ve never seen her before,” adds Brokaw.

At the start of the story, Anna is a successful photographer and a recent divorcee. After meeting and flirting with Dan, she marries Larry (Clive Owen), all the while carrying on a secret affair with Dan. Rather than back away from Anna’s more questionable behavior, Roberts was interested in exploring both her character’s strengths and her flaws. “I had a great amount of trouble with letting her be this incredibly flawed woman. I think she does some really awful things that even at my worst moments, I look like an amateur compared to this woman.

She’s very devious, but I don’t think it’s really calculated.” Overall, Roberts says she admires Closer because, “I think it’s about the plight of these people trying to be closer to each other, to be closer to something really valued in life, to be closer to a truth that maybe none of them will ever be. It’s really more about the intimacy of being compassionate human beings. That’s kind of what they’re secretly or unconsciously trying to attain.”

Alice (Natalie Portman)

“Where is this ‘love’? I can’t see it, I can’t touch it, I can’t feel it. I can hear it. I can hear some words, but I can’t do anything with your easy words.”

“The character of Alice is, in my opinion, Natalie Portman’s arrival as an adult actress,” says Brokaw. “You see her as a fascinating, somewhat mysterious, adult woman who is very sensual and complicated.”

Nichols had first worked with Portman in a production of Chekov’s “The Seagull,” when she was still in her teens. “People don’t quite realize how remarkable an actress she is, because she looks so amazing,” says Nichols, “but she is. I saw her in Closer right from the beginning and she was, the beginning of my casting.”

Portman admits, “this is definitely a new kind of role for me.” The key to Alice, she says, is the conflict inherent in her character. “Alice is really alone when she comes to London, so she makes up her entire world, completely creates herself. Yet, she also has this childlike side. She’s really honest and direct in her feelings, which distinguishes her from the other characters. So though she’s lying about her persona, she’s the most direct, honest character in the film.”

Besides tackling the character of a multi-faceted adult woman, Portman also had to take lessons in pole dancing for the film, in which she goes to work in a posh London strip club. “It was fun. I have a whole new respect for pole dancers because it takes a lot of skill and is physically very demanding, a combination of dance and acrobatics,” she says.

Despite its risqué elements, for Portman, Closer is a very moral tale. “It examines the way people have relationships with each other and how they sometimes get so lost in them that they are sometimes insensitive to the other person’s feelings. It’s kind of like ‘I’m in love. I can be irrational now. It doesn’t matter who I hurt.’ So love becomes this weird excuse for doing a lot of hurtful things to other people.”

Larry (Clive Owen)

“You don’t know the first thing about love because you don’t understand compromise.”

Clive Owen, who plays Larry, the handsome, self-assured dermatologist, originally played Dan in the original London stage production of “Closer.” When he heard Mike Nichols was interested in casting him in the film, he asked if he could play Larry instead. “I loved playing Dan, but going back and playing Larry was a real treat,” he says. “It was like starting all over again because when you play a part you see the whole thing through that character’s perspective. Now I had to reevaluate everything that I thought when I originally did it, switch everything around and see it from Larry’s point of view.”

One thing that hasn’t changed since he first read the play, is his admiration for Marber’s material. “You don’t often get dialogue like this in movies. It’s wonderful to be able to get your teeth into some fantastic dialogue. It’s so meaty with four fantastic parts. Playing any of them would be great.”

“What’s important,” he continues, “is that you like all four characters. All the scenes are intense and for it to really work you have to keep swapping your allegiances. You have to keep empathizing and sympathizing with both sides.”

And that is entirely appropriate to the nature of the story, Owen reasons, “because it’s about human beings. It captures how people are behaving now, that’s what’s so exciting about it.”

Larry is someone who gets his heart broken in the story and resolves to never be hurt again, he contends. In defending himself, he winds up hurting others. “These four people fall in and out of love and show how brutal and tough that can be. By the end you wind up thinking, ‘Why do we do this to ourselves?’”

Working With Nichols

The four principals on Closer enjoyed the rare luxury of having an extended rehearsal period of four weeks prior to the commencement of principal photography, enabling the actors and Mike to really discover these characters and identify them as people in all their different dimensions.

Nichols always rehearses his movies, but in a completely different way from how he rehearses a stage play. The process for movies takes into account the fact that the shooting of films is almost always in bits and pieces and out of sequence. “So the rehearsal process is to decide together what story we are telling,” he says. “The more interior a story, the more mysterious, the more necessary it is to figure out what happens next.”

In the case of Closer, that entailed figuring out what happens in the periods of time that the story skips, large gaps of a year or more between scenes. Another reason Nichols rehearses films is because it enables him to bring the actors together, “so they can explore how they’re going to be with one another, how they really feel about one another. The better the actors are — like the four actors I had for Closer — the better they are at turning what happens between them into the relationships in the film.”

Portman, who had previously worked with Nichols on a stage production of Chekov’s “The Seagull,” says the director’s rehearsal approach was different when they were preparing for Closer. “On stage it was much more about the process of rehearsals,” she says. “Mike just sat back and let everything grow. For the film he took a much more hands-on approach, with suggestions and leading conversations into certain areas. It was like being in a really interesting English class, analyzing the play during rehearsals, bringing in other literary references.”

Law, who says he sometimes enjoys the discoveries that take place during rehearsals more than the actual shooting of the film, found Nichols’ approach to the process unique. “He works like no one else. The wonderful thing is simply to be in his presence, hear his stories, his wonderful references. It’s a very subtle approach. Slowly, you become aware that through just conversing, he is steering you, almost subconsciously, in the direction he wants to take you. It brings out of you this sense of confidence, that you’re the only person for the job so you should never question or doubt yourself.”

The sense of optimism Nichols conveys, had a significant impact on Roberts, she says. “He’s just so clear and enthusiastic. He’s the best cheerleader you could ever want. He’s so encouraging. It’s just incredible. It really does stir up a lot of emotions and it stirs up a lot of conversation and a lot of thoughts. Mike is really profoundly astute at taking these dramatic scenarios that hold hostility and vulgarity and all this really kind of repellant stuff, and he can somehow, in the course of a story or just through his explanation, make it very much something that every person has done or said or experienced.”

“We spent a lot of time talking about the bigger themes of the piece,” says Owen, “how people behave under pressure, how they behave when they’re in love, how they behave when they’ve been wronged. It’s a very subtle approach, but has a way of seeping into your consciousness and coming back later when you start the actual filming.”

Nichols rehearsal approach came to fruition during production, observes Owen. “Mike is so smart and the one thing you realize is that if a director is very smart, everything else falls into place,” he says. “During shooting he does very few takes, which I think has to do with maintaining the freshness of it all, keeping it alive. When you do a number of takes, even though you can refine things, to a certain extent you start locking everything off. You can lose the spirit and life of a scene. But Mike keeps the air in it. There’s also an odd pressure when you know you’re only going to get a couple of shots at any given scene. It adds this wonderful sort of adrenaline.”

Dressing Up and Dressing Down in London

An additional element in Closer is its take on contemporary London and how the four central characters behave in that milieu. “London is such a fascinating, multifaceted city that there’s always something new to explore in a filmic sense and we’ve done that with Closer,” says producer Brokaw. “It shows a real contemporary London, not the romanticized city people of think of, but rather the city people who live here know in all its different colors and textures.”

Mike Nichols sought out award winning theatrical production designer Tim Hatley to design Closer. Despite the fact that Hatley was relatively new to film design Nichols was so impressed with his theatrical work on recent productions of “Private Lives” and “The Crucible” that he had no qualms about bringing him aboard.

Hatley in turn hired Mark Raggett to be his Supervising Art Director, an artist with a long, impressive film resume behind him. Hatley read the play 15 times before he began to plan his design scheme and found “the answer to all my questions about the characters was right there in the text.”

The look and feel of the film is the heart of present-day London. “The heart of the story is about four people in London, not the touristy, picture postcard city, but a London for real people like these people,” says Hatley.

Hatley, Raggett and Set Decorator John Bush noted that every scene in Closer is rife with tension and the sets should reflect the intensity of the dialogue and the interactions. “The characters’ relationships are quite claustrophobic,” says Raggett, “The sets we created and the locations we used all reinforce that feeling.”

For Dan, a poor journalist and unsuccessful novelist, Hatley designed a worn, cramped London flat, which is situated near a market with bookshops and a café. Anna’s photo studio is also her home, and it changes as the story progresses.

The loft-style apartment is rundown at the start of the film, but as Anna becomes more successful, it is transformed — from an eclectic, bohemian photo studio into an elegant workspace and home.

Both Hatley and Raggett say their biggest challenge was creating the lap dance club. Hatley conferred with Nichols, who didn’t want a typically seedy strip joint, but something a little more upscale. He and Raggett researched several London gentlemen’s clubs, and took their cue from The Reform Club with its heavy, detailed moldings, building it from scratch. “Tim created this surreal environment with a staircase of mirrors and translucent walls,” says Raggett. “It perfectly captures the reflective mood of the scene.”

Hatley also conferred with veteran costume designer Ann Roth, with whom Nichols has collaborated since the Broadway smash hit “The Odd Couple” in the 1960s. Traveling from London to New York with huge metal trunks stuffed with models, photographs and sketches, Hatley “laid out the models during the first script read-through, and Ann and I compared colors. It was amazing to work with such an extraordinary seasoned talent.”

Following her last, rather detailed, costuming job on Nichols’ six-hour production of “Angels in America” for HBO, Roth saw this project as a relatively simple fourcharacter piece. “The most interesting character was Dan, played by Jude Law. He was so poor and his clothes were very ratty, dreary and cheap,” says Roth. “They looked it. Yet, at the same time, Dan is a very sexy man, so that was part of the challenge of dressing him.”

Roth understood that, as a journalist, Dan usually had to appear in a shirt, tie and suit — though the clothing had to be inexpensive. “The job was to make him look good in a rotten suit and somehow we did that, fitting him in a mid ‘60s look.”

For Portman’s character Alice, Roth imagined her as a backpacker who traveled and lived out of a sack. “Alice is a free spirit who can just pick up and go. She just needed a pair of pants and a couple of t-shirts,” says Roth.

Anna and Larry were more affluent, but reflecting their generation, still tend to dress down more often than not, according to Roth, and her wardrobe choices reflect that lifestyle choice.

Closer (2004)

Directed by: Mike Nichols

Starring: Julia Roberts, Jude Law, Natalie Portman, Clive Owen, Michael Haley, Colin Stinton, Nick Hobbs, Elizabeth Bower, Rene Costa, Daniel Dresner, Rrenford Junior Fagan

Screenplay by: Patrick Marber

Production Design by: Tim Hatley

Cinematography by: Stephen Goldblatt

Film Editing by: John Bloom, Antonia Van Drimmelen

Costume Design by: Ann Roth

Set Decoration by: John Bush

Art Direction by: Grant Armstrong, Hannah Moseley, Mark Raggett

MPAA Rating: R for sequences of graphic sexual dialogue, nudity / sexuality, language.

Distributed by: Columbia Pictures

Release Date: December 3, 2004

Visits: 150