Taglines: Perversion at its wicked best!

Erika Kohut is a pianist, teaching music. Schubert and Schumann are her forte, but she’s not quite at concert level. She’s approaching middle age, living with her mother who is domineering then submissive; Erika is a victim then combative. With her students she is severe.

She visits a sex shop to watch DVDs; she walks a drive-in theater to stare at couples having sex. Walter is a self-assured student with some musical talent; he auditions for her class and is forthright in his attraction to her. She responds coldly then demands he let her lead. Next she changes the game with a letter, inviting him into her fantasies. How will he respond; how does sex have power over our other faculties?

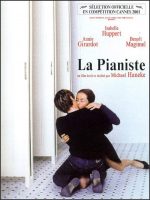

The Piano Teacher (French: La Pianiste) is a 2001 French-Austrian psychological thriller film, written and directed by Michael Haneke, that is based on the 1983 novel of the same name by Elfriede Jelinek, winner of the 2004 Nobel Prize for Literature. It tells the story of an unmarried piano teacher at a Vienna conservatory, living with her mother in a state of emotional and sexual disequilibrium, who is attracted to a pupil but in the end repels him by her need for humiliation and self-harm. At the 2001 Cannes Film Festival it won the Grand Prix, with the two leads, Isabelle Huppert and Benoît Magimel, winning Best Actress and Best Actor.

Film Review for The Piano Teacher

Stiff-backed and unsmiling, her dark eyes as opaque as cough drops, the French actress Isabelle Huppert gives one of her greatest screen performances as Erika Kohut, a haughty, sexually repressed priestess of high culture in Michael Haneke’s powerfully disquieting film, ”The Piano Teacher.”

The largely unsympathetic role of an imperious music instructor who gives master classes at a Viennese conservatory won Ms. Huppert a best-actress award at last year’s Cannes International Film Festival, and it requires her to plunge into dangerous territory that only the most courageous actors would dare to inhabit.

This is not the first time Ms. Huppert, an icon of Gallic severity and self-containment, has portrayed an imperious woman flashing furious messages from behind a forbidding mask. She has relayed similar signals in Olivier Assayas’s ”Destinées,” Benoît Jacquot’s ”School of Flesh” and Claude Chabrol’s ”Ceremony,” to name only three relatively recent films.

The biggest difference between this role and the others is her character’s extreme sexual kinkiness. Erika is a compulsive voyeur who frequents pornographic bookstores and prowls drive-in movies to spy on couples having sex in cars. At home, behind closed bathroom doors, she practices genital self-mutilation while her bossy, meddlesome mother (Annie Girardot), with whom she lives, prepares dinner.

That mother-daughter relationship is embattled, suffocating and incestuous in all but deed. The women sleep side by side on twin beds pushed together, and during their frequent squabbles, they slap each other’s faces. In an unsettling subplot of ”The Piano Teacher,” Erika sadistically torments a female student who also has a domineering mother.

The floodgates open when Erika unexpectedly finds herself ardently pursued by a handsome, worshipful younger student, Walter Klemmer (Benoît Magimel), who idolizes her musicianship and imagines he is in love. But when he declares his passion in the conservatory’s bathroom, Erika refuses to have sex. The two embark on an erotic journey to which Erika, in her infinite perversity, applies the same perfectionist standards she brings to her teaching of Schubert. That composer’s dynamics, she asserts, range (like her own temperament) from ”scream to whisper, not loud to soft.”

Brought to the chaotic realm of sexuality, the rigid rules that help forge a great musician seem ludicrous. Erika is unable to give herself to Walter in any conventional fashion, and her adamant refusal to play the game of love in any ordinary way infuriates and disgusts him. Yet he remains infatuated (or maybe just curious) enough to keep playing along. Erika insists Walter study and follow to the letter a long and detailed set of instructions in which he is to subject her to bondage, pain and humiliation. Ideally, these rituals should be acted out in a situation where her mother overhears, but is powerless to intervene.

In the film’s ugly, climactic scene, Erika’s wishes are granted. But her experience is far different from what she had imagined, and the scene graphically illustrates the difference between ritualized sadomasochism and violent anger. Since he began directing films in the late 1980’s, Mr. Haneke, also a well-regarded German playwright, has shown himself to be a rigorous moral theorist obsessed with the voyeuristic aspect of movies and the dehumanizing effects of television. He has a streak of sadism himself. Watching ”The Piano Teacher,” adapted from Elfriede Jelinek’s 1983 novel, you can sense the relish with which he punishes the audience for its prurient anticipation.

Far from being a titillating sex show, ”The Piano Teacher” has the feel of a clinical case study elevated into a subject of aesthetic and philosophical discourse. Visually, Mr. Haneke is a cool, meticulous formalist who favors elegant shots in which the camera remains stationary. The icy authority with which the film manipulates our expectations recalls his notorious 1997 film, ”Funny Games,” a hair-raising, almost unwatchable essay on screen violence that follows a pair of killers who invade a couple’s comfortable vacation home and methodically torture and kill them and their child. The cruel joke of ”Funny Games” is that the actual violence all takes place off screen.

More recently, in ”Code Unknown,” he investigated the role of spectator, placing the viewer in the excruciatingly uncomfortable shoes of people confronting violence and injustice in public situations where it would be easy for them not to intervene.

When Erika gets what she thought she wanted and emerges emotionally as well as physically battered, you sense the director thumbing his nose and asking us the same question the movie poses to Erika: ”Is this really what you wanted?” In our case, it is a vicarious kinky thrill. The major weakness of the movie is that the day-by-day emotional choreography of Erika’s and Walter’s tango doesn’t track, mostly because Walter’s changes of heart are too abrupt and seem determined by the plot rather than driven by character.

But the issue of voyeurism is only one layer of this film, which is also a glum, post-Freudian meditation on sex, power, repression and Western high culture and the relationship between high art and sexuality. As you listen to Erika’s brilliant, mathematical, note-by-note analysis of a piece of music’s emotional component, she displays the impassioned insight of an artistic genius.

She approvingly describes a Schumann piece as embodying the loss of reason. And there you have the film’s underlying conundrum. Erika is so immersed in the world of art that she imagines that the transcendent paradox of great Romantic music — it maintains a magisterial control even while losing its mind — applies to life as well as art. The saddest message of this almost-great film may be that art and life are not the same and should not be confused.

The Piano Teacher – La Pianiste (2001)

Directed by: Michael Haneke

Starring: Isabelle Huppert, Benoit Magimel, Annie Girardot, Susanne Lothar, Udo Samel, Anna Sigalevitch, Cornelia Köndgen, Gabriele Schuchter, Dieter Berner, Martina Resetarits

Screenplay by: Michael Haneke

Production Design by: Christoph Kanter

Cinematography by: Christian Berger

Film Editing by: Nadine Muse, Monika Willi

Costume Design by: Annette Beaufays

Set Decoration by: Hans Wagner

Music by: Martin Achenbach

MPAA Rating: R for aberrant sexuality including violence, and for language.

Distributed by: Kino International

Release Date: April 12, 2002

Visits: 450